20

The Plot Thickens

It was a very warm morning. Miss Martingale was rehearsing the part of Miss Fancy in a somewhat lackadaisical manner when Lily Jakes of the Sare Arms, aged approximately thirteen summers, burst into the theatre. Panting, and very red-faced. “Miss! There’s a lady to see you!”

“A lady?” she said, going very white as the spectre of Cousin Evangeline raised its ugly head.

“You can stop behaving as if the house was on fire, my girl,” said Mrs Mayhew, who was nearest Miss Lily, in severe tones, “and just speak up sensibly. Has this lady a name?”

“Dunno, mum!” she gasped. “She’s in a state, and Ma said to come and get Miss Martingale, right smart!”

Mrs Mayhew put a supporting arm round Miss Martingale’s waist. “How old is she?”

“Dunno, mum!”

“For the Lord’s sake! Is she old or young?” she snapped.

“A young lady, o’ course,” said Lily Jakes, astounded that this had not immediately penetrated to the minds of Hartington’s Players.

Mrs Mayhew rolled her eyes to High Heaven but did not neglect to give Miss Martingale a comforting squeeze and say: “There, now! It ain’t whom you was afraid of, my dear, and come to think of it, goodness only knows how she could have got wind you were here!”

“Yes. How silly of me. Buh-but no-one does know I am here. I mean, I have no acquaintance in England, really.”

“She never give no name, Miss,” explained Lily.

“Um,” said Miss Martingale, swallowing, and recalling a certain escapade of Ricky’s, “does she have red hair, Lily?”

“No, Miss. Yellow as butter, Miss,” she said on a smug note. “But Ma says, can you come? Acos she be a-bawling all over our parlour.”

“Come along, my dear: I shall accompany you to the inn,” decided Mrs Mayhew, in her grandest voice.

Mr Dinwoody, who had been leaning against the foot of the stage saying nothing throughout the exchange, at this straightened, and followed them silently.

Mrs Jakes met them at the door. “She’s a-bawling, Miss. And said as she didn't believe you was with no theaytricals. Only I spotted it was you she meant, first off!” she congratulated herself.

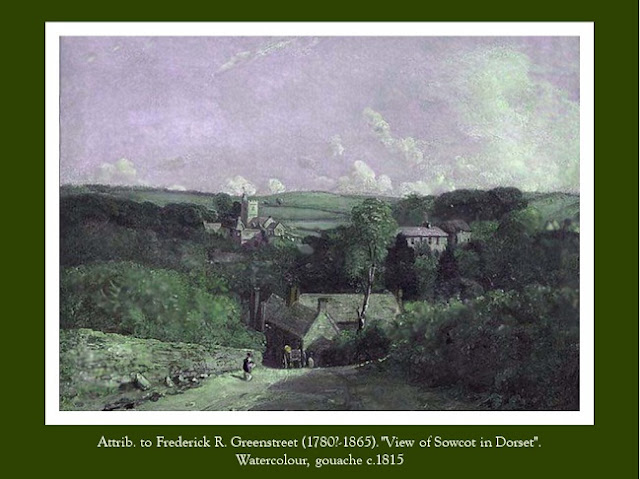

“Aye, acos no-one else ain’t got a little dog what looks like no sausage, not in Sowcot. Nor not down Frenchman’s Cove, neither,” explained Lily helpfully. “Only she said, ’as ow ’e were dead. Only then that Georgy, ’e brung ’im in, and she gives a shriek like you never ’eard and—”

‘That’ll do,” interrupted Mrs Jakes ruthlessly. “A late baby, she were.” She winked at Mrs Mayhew. “What never would of happened if Pa had took advice and used ’is best silk hanker. Got a bit spoilt, see. Well, you don’t pay that much attention, when they come along when you’re over forty and a grandma several times in yer own right, do you, ma’am? What she means is, the young lady was in a right state to start with, only when that Georgy walks in with the little dog, she lets out a shriek to wake the dead and busts out a-bawling all over the parlour. What I put ’er in there, ma’am, seeing as ’ow she wanted one of Mr Hartington’s ladies!” she finished on a triumphant note.

“Give over, Ma,” said Mr Dinwoody stolidly. “Let the dawg see the rabbit, for God's sake.”

Miss Martingale was looking quite stunned: Mrs Mayhew cast one look at her and said firmly: “One deplores the expression, whilst approving the sentiment, Mr Dinwoody. Pray give way, Mrs Jakes,” and forced her way past Mrs Jakes and Lily into the inn, towing Miss Martingale with her. Mr Dinwoody, with a slight sniff, followed, his square face expressionless.

“’Ullo,” said Georgy mildly. “This lady, she thought Troilus was dead.”

And the tear-stained lady sitting opposite him by the cold grate of the Sare Arms’ dingy parlour jumped up and precipitated herself into Miss Martingale’s arms.

“Belle!” she gasped, clasping her to her bosom, willy-nilly. “What on earth—?”

Belle sobbed noisily, gasping out something incoherent through the sobs. Eventually her cousin got her seated again, and drew up a chair beside her, taking her hand in a comforting manner. And Mrs Mayhew, at her grandest, rang the bell and ordered a glass of brandy from the interested Mr Jakes.

“She’s my cousin; Cousin Dearborn’s eldest daughter, Belle Dearborn,” explained Miss Martingale, as Belle, having soaked her cousin’s handkerchief, blew her nose on Mrs Mayhew’s.

“She thought Troilus was dead. And when I brung him in, she thought ’e was ’is ghost, see?” explained Georgy pleasedly. “So she lets out a shriek what would’ve deafened ’em at the back of the gods. –Miss Martingale, what say we was to do the ’And again, and you was to get Mr Hartington to put in a part for a little dog what could turn into a ghost—”

“That’ll do. Run off and practise them haitches of yours,” said Mr Dinwoody drily.

“No! –What yer think?” he persisted.

“Georgy, please be quiet. Can’t you see my Cousin Belle is in a state?”

Georgy sniffed. “I seen Madam in a state like that, and then ’e corfs up a blamed brooch, and she’s ’appy as Larry: smiles all over, you wouldn’t know it were the same woman!”

“Belle is nothing like Madam,” said her cousin in her firmest voice.

“Yes, she is, Miss Martingale! Look at her!” he protested.

She looked at Belle’s tumbled mass of yellow curls under the over-elaborate bonnet, and the wide, tear-drenched blue eyes, and gulped in spite of herself.

Firmly Mrs Mayhew hauled Master Georgy to his feet. “Come on, you can come over to the theatre. Your room is required rather than your company, at this junction. Miss Cressida, dear, you have but to send a message, and I shall precipitate myself to your side, immediate.” Forthwith she sailed out, hauling the protesting Master Trueblood with her.

“I was persuaded,” said Belle, lifting tear-drenched eyes to her cousin’s, “that Mamma had had Troilus put down.”

“Very natural, Miss,” agreed Mr Dinwoody soothingly.

“Yes, well, the thing is, Belle, your servants do not like Cousin Evangeline and so, though I know she does not dream of it, they do not always obey her orders.”

“No,” Belle agreed, mopping at her eyes with Mrs Mayhew’s now very soggy handkerchief. “Good.”

Mr Dinwoody cleared his throat. “I’ll be just outside in the passage, Missy. Holler if you need me.”

“Yes. Thank you,” she said in a distracted manner, not looking at him.

Mr Dinwoody eyed the tear-drenched Belle thoughtfully, but took himself out.

“Now,” said her cousin on a deep breath, seizing Belle’s hands firmly in hers: “what is it, dear Cousin? Are you—are you in trouble?”

“No,” said Belle, sitting up, sniffing hard. “It isn’t me. It’s Jo-ho-hosephine, and he’s ruined her!” she wailed, with a fresh burst of sobs.

“Who?” she croaked, going very pale.

“Cousin Ricky,” gulped Belle.

“The idiot!” said Ricky’s sister fiercely, springing to her feet. Belle watched her dazedly as she marched up and down the dim little parlour, fists clenched. Eventually she came to a stop by the fireplace, took a deep breath, and said: “Belle, are you positive it was he? A slim young man, of medium height, with red hair?”

Belle nodded feebly. “Cousin Ricky,” she repeated. She stared dazedly as her cousin muttered angrily: “This was not in the plan! I shall kill him, the imbecile!”

“His nose is just like yours,” she ventured feebly.

“What? Oh; the damned Martin nose! Yes, we all have it, and I wish I had never inherited it!”

“Um, yes,” agreed Belle limply.

“You had better,” she said with a sigh, sitting down beside her again, “tell me it all.”

It took some time, and the application of more brandy, and a pot of tea and some unromantic but certainly sustaining bread rolls supplied by the sympathetic Mrs Jakes, but eventually the full story was revealed. Ricky had turned up at Dearborn House, and had at first attempted to pay court to Belle herself. Very much encouraged by both Cousin Dearborn and his wife.

“But you did not care for him?” asked his sister cautiously.

“No. He did not strike me,” said Belle, sniffing but earnest, “as sincere.”

In that case she had a deal more sense than her cousin would have given her credit for. Or, perhaps, simply more reliable instincts. “Go on. Did Ricky turn to Josephine?”

“Not exactly. I blush to admit it, of my own sister, but she threw herself at him,” said Belle. Blushing.

“I see.” She could, indeed, envisage it all too clearly. Ricky was very good at allowing dim young women to throw themselves at him. And provided they were pretty enough, very good at not refusing them when they did so. But in this case, in view of the larger scheme of things, could he not have refrained? thought his sister angrily. Er—well, no, she reflected uneasily. Perhaps this had been part of Ricky’s plan all along, though it had certainly not been a part that he had ever revealed to either of his sisters. Ruining one of the Dearborn daughters would certainly be a very pretty revenge on Cousin Dearborn for having enjoyed the inheritance that should have been Papa’s all these years. Not to say, for his recent treatment of Major Martin’s daughter. Oh, dear. What an awful pickle.

“Um, did Cousin Dearborn and Cousin Evangeline encourage it, Belle?” she asked, clearing her throat.

“Yes, for they thought—well, we all thought—that he intentioned marriage! And Papa was very pleased and promised Josephine quite a large dowry, and said that of course Cousin Ricky must live with us for a little, there was no need to spend money on refurbishing his own house.”

Miss Martingale took a deep breath. “Was Ricky’s twenty-fifth birthday mentioned in all of this, Belle?”

“Um… I do not think it was,” she said in a puzzled voice. “Why?”

“Never mind. So he persuaded poor Josephine to run off with him, did he?”

“Yes,” she said, a large tear rolling down her rounded cheek. “She left Papa a note, saying they were eloping, and he said it was a piece of impertinence, and Cousin Ricky was a jackanapes, but at least it would spare him the expense of the wedding. So he was not so very angry, you see.”

“Not yet, you mean.”

“Yes,” said Belle, as another tear dripped. “As it turned out, he only took her as far as Axminster. And—and took a very poor set of rooms, in an unpleasant quarter of the town.”

“Yes, well, that’s Ricky all over,” admitted his sister. “Did he leave her there, Belle?”

“Yes,” said Miss Dearborn drearily, scrubbing at her eyes with the balled-up handkerchief. “After a week. He left her with almost no money, but when the landlady heard who Papa was, she agreed to let her stay while a note was sent home. And—and Papa was furious, Cressida, and said she was no daughter of his, and cast her off ut-ter-ly!” she wailed, with fresh tears.

“Hush,” said her cousin, once again putting her arms around her. “Don’t cry, Belle, dear: we’ll rescue her.”

“Um, ye-es… But you see, I was persuaded you were with Lord Sare, Cousin! And—and Papa wrote him a very stiff note, and said that he must divulge Cousin Ricky’s whereabouts, and—and endeavoured to enlist his aid in forcing him to marry her. But he wrote back that he had never laid eyes on him. Buh-but I thought that perhaps he was shielding him because a girl who could run off with a gentleman could nuh-not be thought a proper match, and if only I could speak to you, you might help to persuade him!”

“Um, I have not seen Lord Sare, I’m afraid. Do your parents know you’re here?”

“No,” said Belle on a defiant note, holding her plump chin up very high. “For Papa was obdurate, and said that was that, and if Lord Sare could not help there was no use thinking we should be able to find Cousin Ricky, and Josephine was ruined, and was no daughter of his. And Mamma ordered that her name should never be spoken again. But I did speak it. And I told her that I could not believe it was a Christian deed to cast off one’s own daughter, however badly she might have behaved!”

“Good for you, Miss!” said a loud voice from the doorway.

Miss Martingale reddened. “Mr Dinwoody, have you been listening?”

“Yes,” he said simply, coming in. “Thought it might be a situation what you couldn’t cope with, Missy. Not but what you’re capable of coping with most. But it might of called for direct measures.” He made a fist and looked at it thoughtfully.

Belle gave a tremulous smile. “Thank you, sir.”

“Did your Ma relent?” he asked with interest.

“No. She was very angry with me.”

“Help, did she send you to bed without dinner?” asked her cousin involuntarily.

“Yes. But I did not care! And I had my pin money, or some of it, but I did not think it was enough, so I waited until Mamma was out of the house, and got out of my window—it’s quite easy, I used to do it all the time when I was a little girl: that big elm tree is so very near. And I crept in through the back door and stole some money out of Mamma’s drawer. And one of the stable boys caught me creeping outside again, and I thought it was all up with me, but he was very helpful and harnessed up the pony cart, and drove me all the way to Axminster!” she finished pleasedly.

“Was it Alf Hollis?” asked her cousin, smiling a little.

“Why, yes!” she said in astonishment. “How did you guess?”

“It was he who saved Troilus. We owe him a lot, then,” she concluded. “And did you see Josephine?”

“Yes. She—she was very down,” said Belle through trembling lips. “But after I had paid what was owing the landlady said she could stay until I had contacted Lord Sare. I was not sure how to go about it, but Hollis got me onto the stage. He wished to come with me, but there was not enough money for two. And he said he would look for another place, and not to worry about him.”

“I see. But how did you get here from Dorchester, Belle?”

“Hollis said it would be best to ask at the coaching inn, and so I did, and the landlord knew of a fellow who was coming this way with a waggon.”

“You came on a waggon?” she said limply.

“Yes. Well, it was not very comfortable, I suppose,” said Miss Dearborn on a defiant note, “and the fellow was rather familiar in his conversation, though I suppose quite well-meaning, but I thought of Josephine and did not care. Fuh-for nuh-nothing can compare with her plight,” she said, the defiance vanishing and the lip beginning to tremble.

“No, indeed! You have been very brave!” said her cousin warmly.

“Aye: good for you,” murmured Mr Dinwoody.

Miss Dearborn gave him a tremulous smile and continued: “But the man was only coming to the village inn, and did not know how to get to Sare Park; but as it turned out, of course, that was most fortunate, or I should have gone quite astray and never found you, dearest Cressida!”

Mr Dinwoody cleared his throat. “No, well, most fellows with waggons would tend to drop in at the inn, Miss Dearborn. But you done really well.”

“Thank you. So—so you have been acting, have you, Cressida?” she said in a bewildered voice.

“Yes. I’ll tell you all about it later. But now, I think it might be best if you had a good rest, Belle. Um—oh, dear: all the rooms here are taken,” she realised in dismay.

Mr Dinwoody said hurriedly: “I think Miss Dearborn would rather be with you at Ma Jessop’s. Dare say Miss Tilda won’t mind giving up her bed, eh? Come on, Miss, we’ll take you over.”

“Yes,” Belle’s cousin approved, getting up. “I’m sure Tilda will be happy to go to Mrs Solly’s. Come along, Belle.”

Numbly Miss Dearborn nodded, and, as the blue-chinned person whose name she had not caught was now holding the door for them, exited, clutching her Cousin Cressida’s hand very tightly.

“It’s all very well,” concluded Mr Dinwoody as Miss Martingale’s well-wishers convened round Mrs Jessop’s parlour table, Miss Dearborn having gone out like a light in Tilda’s narrow bed with Troilus on her feet, “and the lass done good, but now what? Do we let them parents know she’s here and if so, do they cast her off as well?”

“They probably already done that,” noted Mrs Mayhew sourly.

Mr Lefayne had accompanied Mrs Mayhew and Mrs Pontifex over to the Sare Apartments. “Very likely, Margery,” he agreed grimly. “Given that it must have taken her several days to get here.”

“Yes. But more fundamentally, who is to take care of Josephine?” worried her cousin.

Mr Dinwoody put a hard hand over hers. “Dunno, yet. Because we ain’t sorted you out yet, Missy, has we? You better write that note to Lord Sare, and damn’ quick.”

“Yes,” agreed Sid before she could open her mouth.

She sighed. “There is no proof that he may be the sort of man that will care about my poor cousin, sir. In fact, given his class, every likelihood that he will not be.”

“Might be a fellow what believes in doing ’is dooty,” offered Mr Dinwoody.

“Well, pigs might fly, Dinwoody, but we should at least offer him the chance to demonstrate whether he be a man of honour. –Write it,” Sid ordered Miss Martingale.

“Very well,” she said with a sigh.

A slight hiatus intervened in which it was discovered that Mrs Jessop, being not much of hand with the writing, had no pen, ink or paper, and in which Mrs Jessop volunteered to fetch the same from Mr Bones, and did so, returning with not only the writing materials but the interested umbrella-maker himself.

“Which, if so be the poor girl needs a roof over her head, Miss, she can come to me,” said the grim landlady. “And between you and me, Miss Lucy’s getting a bit past it, not that her stitchery ain’t as fine as nothing, only she’s getting very slow. So the poor young lady could be trained up to help Mr Bones. And more custom to be expected, acos there’s Mr French’s daughter, and Mrs Dunne’s girls a-growing up, and Mrs Garbutt allowed as that Dotty could have a parasol like a grown-up lady only t’other day. Well, sort of grinned as she said it, but she meant it, sure enough,” she assured them.

“You are both very kind,” said Josephine’s cousin, smiling mistily at them. “I do not think that Josephine has any skill at sewing, but I am sure she could learn.”

“Aye. Thank you both very much, it's extremely decent of you,” said Sid on a firm note. “—Write, Miss Martingale.”

Sighing, she wrote.

“I'll take it up to Sare Park meself,” volunteered Mr Dinwoody.

“Good man. Er…” Sid eyed him dubiously. “Can you make sure you give it to Lord Sare himself?”

“I can promise you that,” he returned grimly, striding out.

Sid got up. “Miss Martingale, I think someone should rescue Miss Josephine without delay. I don’t like the sound of that landlady. I’ll go and tell Harold the lot, and Hetty and I can go over to Axminster. If we don’t get back in time for the performance, David can take the Beau.”

Miss Martingale sprang up and seized both of his hands in hers. “Oh, thank you, Mr Lefayne!”

“Miss Martingale,” he said with a little sigh, “it’s the least I can do.”

There was a little silence after his exit.

“Never thought ’e would, Miss Cressida, dear, to tell you the truth,” said Mrs Mayhew, clearing her throat.

She smiled mistily. “He is a man of decent instincts.”

“This one’s pretty enough,” noted Mrs Hetty, jerking her head in the direction of the bedroom. “Dare say she might fancy treading the boards with us if the family won’t have her back and Lord S. looks down his nose at them.”

Mrs Mayhew snorted. “Which, if it’s the nose as I’m thinking of, what never offered so much as a country dance to any of us actresses, so supper me no suppers, he probably will, so don’t you go and get your hopes up too much, Miss Cressida! It’s only men as believes all that pretty stuff about duty and honour, you know, my dear. Us women, at least any of us what ’ave lived long enough to tell the tale, can tell you better; eh, Mrs Jessop?”

“That’s for certain sure, ma’am!” agreed the landlady at her grimmest.

“Aye. Never ’eard of no good come out of Sare Park, and I’ve lived in Sowcot all me life, man and boy,” concurred Mr Bones.

That seemed to be that, then; and Major Martin’s daughter, quickly wiping her eyes and smiling bravely, agreed: “I am sure you’re right. But we had best let them try.”

“Yes. And then,” said Mrs Mayhew kindly, “you can come to us. We’ll see you right. Lud, and seen worse, on the boards, have we not, Hetty?”

Mrs Pontifex concurred feelingly. Whereupon, the grim Mrs Jessop having produced a jug of porter and the lugubrious Mr Bones a small flask of something to be judiciously added in order to brighten it up, the two actresses duly gave the company chapter and verse.

Next chapter:

https://theoldchiphat.blogspot.com/2023/02/character-roles.html

No comments:

Post a Comment