17

The Dorchester Season

“One had not realised that Dorchester was an inland town,” said Mrs Mayhew at her most gracious, waving her fan languidly, her feet up on Mrs Plummer’s chaise longue. –Its owner had hitherto thought of it as a “sofy.” She had been highly gratified to learn that it was a chaise longue, and quite in the style of the best London salons. And had not thought to enquire whether her new boarder was closely acquaint with the best London salons.

“Oh, yes, Mrs Mayhew!” Mrs Plummer now hastened to assure her guest. “But thought to be quite ’ealthy to the constituence!”

Mrs Mayhew agreed that it was, indeed, quite salubrious.

“Salubrious,” said Mrs Plummer, rolling it round her tongue. “Yes, indeed, ma’am. May I venture to enquire, if you would care for a dish of tay, ma’am?”

Mrs Mayhew allowing graciously that she would, Mrs Plummer rang her bell loudly and Jane Brown shot in, panting. “Yes, mum?”

Loftily Mrs Plummer ordered up the tea: the best brand, please, Jane. Looking puzzled, Jane gave a bob, and shot out again. “What she mean, best brand?” she said to Cook in the kitchen.

“What she means is, them new theatrical boarders ’ave got to think she’s a lady. Which means she’s a-gonna make great play of unlocking this ’ere box,” she noted, handing Jane the locked tea caddy which held the household’s residue of tea.

Jane looked puzzled. “But you got some tea, Cook.”

“Right, and it’s the same as what she’s locked up in this. Just put it on the tray, Jane. –Oh, well, good for ’er,” Cook recognised: “she’s buried three husbands, and lost two sons at that blamed Waterloo, and come up smiling. But in my opinion, Jane Brown, theatricals ain’t no better than what they should be, fancy airs and graces or not!”

“T’other lady give me a handkerchief. Well, it was tore, but still nice.”

Cook sniffed. “Too lazy to mend it, that’s what. She in ’er room primping, is she?”

Jane Brown allowing as she was, she was dispatched upstairs to give her a shout. Because Cook wasn’t going to make two lots of tea for no theatricals!

Mrs Deane’s door was locked so Jane perforce shouted through it: “Tea, mum! Cook says, do yer want it?”

“I’m doing my hair, dear!” came a sepulchral reply.

Jane Brown hesitated, but after all, the lady had give her a handkerchief. “I can bring yer up a cup, mum!”

“Very well, then, dear, ta very much!”

When Jane panted up ten minutes later with the tea, the door was opened by a smiling Mrs Deane, clad in a voluminous wrapper. It had a few strange inky splashes on it, but these did not strike the innocent Jane’s eye. The hair could just be seen to be pinned up in a myriad little snails and corkscrews, under a discreet black scarf, worn turbanwise.

“Thanks, dear. My sister in the parlour, is she?”

“Yes, mum. With the mistress, mum. Talking fancy.”

“Thought so!” said Mrs Deane with a husky laugh, seizing the cup. “I’ll leave ’em to it!” She nodded, and disappeared.

“Well?” said Cook as the little housemaid reappeared.

“Eh?”

Cook rolled her eyes to High Heaven. “The hair! Was she— Never mind. We might as well have ours. Go on, you can pour.”

Beaming, for this was not a privilege commonly accorded her humble self, Jane poured.

Mr Deane buttered a bun lavishly. “Damn’ good. Go on, Dinwoody: help yourself.”

Mr Deane was not required for rehearsal this afternoon, and Mr Hartington had sent Mr Dinwoody to their lodgings with a message for him. “Thanks, Mr Daniel, don’t mind if I do.” Mr Dinwoody buttered a bun and Mr Deane passed him the raspberry jam, noting that t’other day Mrs Fairweather had served them with clotted cream and the jam.

“New part going well, sir?” asked Mr Dinwoody with a twinkle in his eye.

“Eh?” said Mr Deane through bun and jam. “Oh: the stuff I’m mugging up for the autumn? Well enough, I suppose. I say, she gave us a slap-up dinner last night! Made our Cook’s best efforts look sick, I can tell you! –At Beau Buxleigh’s,” he explained.

Mr Dinwoody expressed interest, and duly had the previous night’s entire menu listed for him, in great detail. “Slap-up is the word, sir,” he agreed kindly. “Mr Haitch happy ’ere, is ’e?”

“Happy?” Words evidently failed Mr Deane: he waved a jammy hand helplessly in the air.

“I see, sir: as a pig in muck,” said Mr Dinwoody primly.

Mr Deane choked, and had to administer a sip of ale. Possibly not everyone’s preferred tipple with jammy buns, but Mrs Fairweather had kindly procured a jug of it for him. “He’d marry her tomorrow,” he admitted.

Mr Dinwoody coughed. “Is she a widow?”

Mr Deane’s eyes twinkled. “Well, no, Dinwoody, that is one impediment, admittedly!”

Grinning, Mr Dinwoody conceded it would be. And advised Mr Deane that he had better read that note, for Mr Hartington had said it was important.

“Eh? I’ll be seeing him at dinnertime! –Oh, very well.” Mr Deane read it. He shrugged. “He wants to rehearse All In The Mind tomorrow. Does he imagine I’ve forgotten my lines already?”

“Dunno. I could hear ’em for you, Mr Deane, sir.”

“Oh—all right, then. Let’s finish the buns, though!”

They finished the buns, and then, as Mr Dinwoody heard the actor’s lines, in which he was word-perfect, the ale. After which Mrs Fairweather bustled in, beaming all over her round, red-cheeked face, and asked if they would like another jug fetched. What a woman!

“Doing them proud, she is,” Mr Dinwoody explained placidly to Georgy and Miss Martingale, as a sweating Mr Hartington rehearsed his cast next day in All In The Mind. According to him, those that had not forgotten their lines had forgotten their moves.

“Mrs Warburton’s doing us proud!” retorted Georgy immediately.

“Yes,” agreed Miss Martingale with a happy sigh.

“She likes dogs,” Georgy explained.

Mr Dinwoody’s shrewd eye twinkled, but he merely said: “Good.”

“She gave him a wonderful meaty bone, and merely laughed when he tried to bury the remains in her parsley bed,” said Troilus’s mistress with another happy sigh.

“That’s good,” he said, varying the theme slightly.

“And last night—” Georgy detailed the supper. Almost as good as Mrs Fairweather’s. Except that Mrs Warburton apparently made you eat a salad.

“Salads is good for the innards, young shaver,” replied Mr Dinwoody solemnly.

“Yes. She has such a lovely little kitchen garden,” said Miss Martingale dreamily.

“She misses ’er’s, what she made at Mr B.’s!” hissed Georgy informatively.

Expressing interest, Mr Dinwoody was duly told all about it.

“But Mrs Warburton, she’s got a apple tree, and a— What was that other one?” he said to Miss Martingale. “Had them funny little wrinkled green things on it.”

“Des coings.” She looked apologetically at Mr Dinwoody. “I’ve forgotten the English word.”

“Anyroad, they ain’t ripe, and yer can’t eat ’em off the tree, you gotta cook them. But she’s got currant bushes and strawberries!”

“Lord love a duck,” replied Mr Dinwoody obligingly.

Promptly Georgy described your typical strawberry plant, in absolute and minute detail.

“Yes,” said Miss Martingale dreamily. “Delicious. They are almost over, but she gave us some with cream yesterday…”

“Happy, then, are you?” said Mr Dinwoody stolidly.

Apparently they were—yes. Tilda coming off at that moment, she was able to confirm that she was happy, too. Only fancy, Mr Dinwoody, their landlady had given them fresh strawberries! Ignoring Georgy’s interpolation that they’d told him that, Mr Dinwoody encouraged her placidly.

“’Ullo, Mr Smith, sir,” said Mr Dinwoody in a cautious tone, entering the ancient Duck and Plover to find his early appointment waiting for him.

The man who looked like Mr Peebles, last seen departing Mr Twin’s house in Sowcot at dead of night, responded placidly: “Hullo, Dinwoody.”

Grinning very much, Mr Dinwoody sat down at his table. “Thought this was your county? Ain’t you afraid of being reckernized?”

“Not yet,” he said placidly. “So?”

“Happy as pigs in muck!” said Mr Dinwoody with a sudden yelp of laughter. Gleefully he described the delights of the Dorchester landladies. Ending: “Mrs Warburton’s even got a kitchen garden, with strawberries and currants and I dunno what. Oh, yes: a quince tree!”

“Splendid.” He waved for the waiter, and there was a hiatus while they both ordered breakfast. “So, it lacks only a widow for Mr Hartington, does it?”

Mr Dinwoody broke down in a spluttering fit, gasping: “It do that! –No, well,” he admitted, blowing his nose on a voluminous spotted kerchief, “there is a widow, just come to Mrs Fairweather’s. A Mrs Anstey. Lovely-looking woman: tallish, but well built, if you takes my meaning. Fair. Blue eyes.” He eyed him thoughtfully: there had been some sort of reaction when he’d mentioned the widow’s name. “Met ’er, have you? She’s a foreign lady.”

“What sort of foreign?” he said neutrally.

“Lumme, don’t ask me, sir!” responded Mr Dinwoody.

Oddly enough, the man who looked like Mr Peebles smiled very much at this response, and said: “Very well, then, Dinwoody, I shall not. Do he object to foreign?”

“Eh? Mr Haitch? Well, no—don’t think so. Not if it comes with—” He described appropriate shapes in the air, and winked. “Well, think she’d have to have a few pennies put by, he don’t envisage spending his declining years supporting one, far’s I can make out. But she looks as if she might. Only thing is,” he said, lowering his voice conspiratorially: “can she cook?”

At this the man who looked like Mr Peebles broke down and went into gales of laughter. So much so that any resemblance to the meek little clerk disappeared.

A substantial breakfast then being brought, there was another hiatus. After which the two got down to serious talk.

“Um,” finished Mr Dinwoody, scratching his blue chin, “Lefayne suspects. Over’eard ’im and Missy talking about it when they was on the back of the waggon.”

“Seriously?”

“Dunno. He’s got the brains, but will ’e ever bother to act on any suspicion? We-ell… will ’e believe his own theories enough to act, is one point,” he said shrewdly. “He did say he’d write to Beau Buxleigh. Well,” he concluded, “you better lie low.”

“I should take that advice seriously, Dinwoody, were it not that I am a firm believer in the adage that it’s the early bird that catches the worm. And Lefayne don’t strike me as one that would bother to get out of his pit at crack of dawn in the hope of catching any worms. –Well,” he said with a shrug, “this morning must illustrate the point. Any fellow worth his salt would have tracked you here.”

“Any of our fellows would—aye. He’s only an actor,” said Mr Dinwoody tolerantly.

“Quite. –Oh: did you find Ricky Martin’s lodging?”

“Of course. Snug enough. Don’t think he’s paying the landlady in cash, mind you.” He shrugged. “Nothing to it. He’s the sort that would think to take the precaution of preparing a bolt-hole for himself, just in case it might be needed.”

“Yes. Well, I must go,” he said with a smothered sigh, getting up.

Mr Dinwoody also rose, eyeing him uncertainly. “Is everything all right?”

The man who looked like Mr Peebles gave a twisted smile. “As all right as can be expected. Given that I have—er—changed my profession. Well—next week, same time? And a message to Twin, if it’s urgent.” He held out his hand.

Mr Dinwoody wrung it fiercely. “Take care, Mr Smith.”

“You take care, yourself!” he said with a little laugh. He picked up his hat, and went swiftly out.

Slowly Mr Dinwoody reached for his battered tricorne. “Damned fool,” he said under his breath. “Why make everything so damned complicated, when— Oh, well.” Shrugging, he went slowly out into a fine summer’s day.

Mrs Fairweather had not expected to get so many lodgers in the middle of summer and perhaps her awareness of their scarcity in Dorchester at this season was a factor in her pampering of her guests. On the other hand, there was little doubt that she was a liberally-disposed woman and that at any season her lodgers never went short. Indeed, old Mr Norton, who had lived at Mrs Fairweather’s this ten year past, placidly confirmed it, in his Dorsetman’s slow rumble. And, at Mr Deane’s urging, placidly described the winter dinners that lady was wont to serve up. Mr Deane sighed deeply.

“Don’t think I’ve ever actually seen a baron of beef,” put in Mr Vanburgh with bright-eyed interest.

Not perceiving that there was something of the sardonic in this interest of the comic’s, Mr Norton, displaying actual animation, replied: “Ah! Now, sir, Mrs Fairweather’s barons do ’ave to be seen to be believed!” Forthwith describing them to the best of his ability.

“’Uge,” elaborated one, Jessie Sharp, helpfully.

“Aye: huge they be, Jessie,” said the elderly lodger kindly.

Mr Deane grinned. “Aye. Well, Mr Norton, I’ve been in lodgings all over the country, and for one awful year in Scotland, too: and I’ve never been fed as well as here, I can tell you!”

“I can believe that, sir,” said Mr Norton solemnly, nodding his large head. “Pop off and tell Mistress all but one of the acting gents is back, would you, Jessie, me dear?”

Suddenly recollecting that she was in fact in the parlour on an official errand pertaining to her duties, and not as of right, Jessie popped.

“She’s doing lamb for tonight,” said Mr Norton helpfully.

The actors grinned, and nodded.

“You’ll miss out when you do your show, won’t you?” he added on an anxious note.

“No, indeed, sir,” said Mr Vanburgh, rising politely as Mrs Anstey came into the parlour, “for she has promised to do us a hot dinner at five and then supper after the evening show. –Good evening, ma’am.”

Mr Deane also rose. “Good evening, Mrs Anstey.”

Mr Norton, bobbing his large head, half rose from his accustomed armchair; but Mrs Anstey, smiling, said: “Good evening, gentlemen. Please, do not get up, Mr Norton,” and the elderly lodger subsided again.

“So, I am not late for dinner, I think?” she said composedly, allowing Mr Deane to show her to a chair.

“No, ma’am, she serves it at seven sharp. What in the old days, you wouldn’t of. But you have to change with the times,” said Mr Norton, nodding.

“That’s right!” said a loud, cheerful voice; and Mr Fairweather himself came in, smiling. “’Evening, all! My Bess says to tell you, as starting this Fridee, dinner’ll be set forward to five o’clock, on account of the theatrical gents. And hope it’s not to inconvenience.”

“Aye, we know,” agreed Mr Norton, nodding. “Sip of something, then, Jim?”

“Why not?” he agreed, opening a large cabinet. “Name it, ladies and gents!”

The ladies and gents were now all aware that the cabinet contained a choice of rum, gin, or port wine, the last-named being a favourite of Mrs Fairweather. It was Mr Fairweather’s pleasant custom to dispense sips of these nectars before and after dinner. When, that was, he was home, which was not very often. It was not absolutely plain what the genial Mr Fairweather actually did. And as yet Mr Norton had certainly not been able to clarify this for the theatricals. And nor had Miss Spink or Mr Paffey, the other permanent lodgers in residence.

Miss Spink coming in upon her cue, her usual drop was poured for her. –A mixed drop, gin with a dash of rum in it “to brighten it up.” It certainly appeared to brighten up the tall, angular Miss Spink: her wide, flat cheeks noticeably reddened and her manner became almost lively. Miss Spink was a seamstress, employed by a tailor in the town, in a very good way of business. Stitchery only: no cutting, of course. And to say truth Mr Grose only allowed her to do the seams of the garments when they were very much under pressure. But she was wholly responsible for the linings and had two apprentices under her!

“So, ’ow was work, Miss Spink?” Mr Norton now asked kindly. “Any new nobs come in?”

Miss Spink bobbed her bony head at him. “Why, yes, indeed, Mr Norton! Most exciting indeed: we have had Lord Sare himself!”

“’Oo?” said Mr Fairweather blankly.

“Now, don’t tell me you’ve never ’eard of ’im!” said Miss Spink, giving him one of her angular head bobs. “Lord Sare, from Sare Park, down near the coast. Owns ’alf the county.”

“The southern half, eh?” said Mr Deane kindly.

“Did you say Sare?” asked Mr Vanburgh on a weak note.

“That’s right, Mr Vanburgh!” she replied happily. “Normally, his Lordship patronises the great Mr Weston of London town himself! –And drove up to Mr Grose’s door in his curricle and four,” she said with a deep sigh. “Chestnuts. Us workers seen ’im from the attic,” she explained.

“Daniel, wake up!” said Mr Vanburgh sharply to his colleague. “That is the same name! You remember, when I took the part of the lawyer’s clerk, relative to that Horse Guard’s piece!”

“Eh? Horse G— Oh. Yes, so ’tis. Um, well, they did say he lived in Dorset, Vic.”

“Er—yes. I beg your pardon, Miss Spink,” he said lamely.

“Not at all, sir. Most understandable, I’m sure. A true gentleman, and spoke very kindly to Mr Grose, and said he remembered his grandfather! And ordered up a greatcoat, a riding-coat, a pair of breeches, and two cloaks!”

“How old would he be?” asked Mr Vanburgh curiously.

Miss Spink could not say. But Mr Grose had assured them he was a true gentleman.

“If he remembered his grandfather…” said Mr Deane dubiously.

“Indeed, sir! Old Mr Grose made him his very first pair of little riding-breeches, for his first pony! That were back in the old Lord’s day. Mr Grose remembers Mr John, his Lordship’s father, very well. Died at Trafalgar, at Lord Nelson’s side,” she said, shaking her head.

“Eh?” said Mr Vanburgh limply.

“Oh, yes, indeed, sir: very sad!” she said brightly with another bob of the head.

“Daniel, didn’t Sid say that Peebles’s father had died at Trafalgar at Lord Nelson’s side?” said Mr Vanburgh.

“Mm? Oh, dare say. –Very sad, yes,” he said kindly to Miss Spink. “Dare say a lot of fellows did, y’know; it were a great battle,” he said to Mr Vanburgh. “And Dorset’s a coastal county, when all’s said and done.”

“Yes: a-many of our brave lads fell with Admiral Nelson,” said Miss Spink with a deep sigh.

“Aye; aye,” agreed Mr Norton gloomily.

The actors exchanged glances and bit their lips, realising that given that all the persons present were locals save Mrs Anstey, that had possibly not been at all a tactful reminder. And Mr Vanburgh said quickly, smiling at Miss Spink: “I am very glad to hear that Lord Sare is giving the local tradespeople some custom.”

Very gratified, Miss Spink bobbed her head several times and imparted the interesting further fact that the last Lord Sare had never bought nothing in the county, not so much as a neckcloth!

Mr Paffey, who was a clerk with a local stationer and bookseller, then hastening in, a further sip was dispensed and Mr Fairweather asked genially how his day had gone.

It had gone very well and Mr Paffey with his own hands had sold three reams of best hot-pressed writing paper to a gentleman with a curricle and four! Mr Paffey removed his pince-nez and polished them busily, his red-cheeked, robin-like little face all good-natured twinkles.

“Chestnuts?” asked Miss Spink breathlessly.

“I think they were, aye. But you will never guess who ’e turned out to be!” Mr Paffey replaced the pince-nez and twinkled at her through them.

“I wager I shall, Mr Paffey, for we ’ad ’im at Mr Grose’s ourselves! Lord Sare? There!” she cried triumphantly, as he nodded, twinkling very much.

“Three reams is a lot of paper, I think?” noted Mrs Anstey kindly.

“Indeed, madam!” said the clerk pleasedly. “It is not often we get such a large private order.”

“Don’t these fine gents usually have their name engraved on it, or some such?” asked Mr Deane hazily.

“Strutt & Sons will take orders for such, Mr Deane,” said Mr Paffey hurriedly.

“They send ’em out to Quirke’s. Jobbing printers. Playhouse Lane. Just off the high street, it is. You’ll have passed it, sirs. Mr Quirke, he’s Mr Strutt’s brother-in-law,” said Mr Fairweather helpfully.

Mr Paffey nodded and twinkled, Miss Spink gave several angular bobs, and Mr Norton nodded his large head hard. The actors smiled feebly and agreed that that must be convenient.

“You missed some real excitement before dinner, Harold,” drawled Mr Vanburgh, lounging into Mr Hartington’s room that evening as the actor-manager was preparing for bed. “Noddy Norton on barons of beef, Miss Spink and Paffey on Lord Sare’s actual in-person patronage of their respective establishments—!” He shrugged and laughed.

“Good,” said Mr Hartington simply.

“Mm…” Mr Vanburgh wandered over and perched on the edge of the bed. “Harold, does the name Sare not ring any bells?”

“No. Um… Hang on: old Neddy Sare!” he produced brilliantly.

“Yes, we know all about him. Sid has not mentioned Miss Martingale in that connection, has he?”

“No,” he said, yawning. “Why?”

Mr Vanburgh got up slowly. “Nothing. Dare say he thought you wouldn't be interested.”

Mr Hartington swung round and stared at him. “Vic, he’s not conceived an interest there, for God’s sake, has he?”

Mr Vanburgh was about to give an airy shrug. He thought better of it. “Er—well, yes, I rather think he has. Not one of his usual things.”

“Never tell me he thinks of her as his daughter!” he said sardonically.

“No, I won’t tell you that, Harold.”

“Well,” he said uneasily, “Beau did mention that he affected her, I’ll admit that, Vic. He seemed sure of it, for what that’s worth.”

“Aye. He has taken,” said Mr Vanburgh slowly, “an unusual sort of interest in her. Caring for her welfare, I suppose you’d say. Bothering more about her than I’ve ever seen him do about any girl.”

“You never knew little Rosemary Davis, did you? –No. That was years back. She was a lady, too. She wasn’t Miss Martingale’s type, though: far from it. Big brown eyes, piles of brown curls, cuddly little figure. He fell for her in a big way. Mind you, he was little more than a lad at the time. Would have married her, an’ all. The father wouldn’t hear of it, of course.”

Mr Vanburgh raised his eyebrows a little, but noted: “I suppose any man may fall.”

“Yes,” said Mr Hartington uneasily. Victor Vanburgh was a man who normally kept his own counsel. It was not at all like him to bring up such a topic merely for the pleasure of gossiping. “Um, well, he’s writing again, y’know. Let’s hope that keeps him occupied.”

“Mm. Well, one of his problems is that when he don’t have enough to occupy his mind, he gets into trouble,” said Mr Vanburgh drily, opening the door. “Witness the latest episode with the dark-eyed widow. Good-night, Harold.”

“Good-night. –Oh: early call tomorrow,” he reminded him.

“Yes. I’ll fetch Sid for it, shall I?”

“Eh? If you want, yes,” he said in surprise.

Nodding, Mr Vanburgh wandered off to his room.

Mr Hartington closed his door slowly, frowning. Old Beau had been pretty sure that Sid affected little Miss Martingale, hadn’t he? Yes, but… He thought of the generously-curved, large-eyed Mrs Greatorex, and sighed gustily. No, well, that was not the act of a lovelorn man, far from it! And every ingénue they had ever had had fallen for Sid, so whatever Miss Martingale felt, lady or not, could possibly be discounted. Um… but was he holding off because she was a lady? Harold swallowed. That was just possible—yes. He knew that Sid Bottomley was no despoiler of innocent maidens. And that, given his reaction to the last mention of Rosemary Davis, about a year since, he did not consider himself fit to offer honourable marriage to a lady. Only… say he was to settle down, as threatened, in a respectable little house in St John’s Wood? Would he think that fit to be offered to Miss Martingale? Given that, lady or not, she didn’t seem to have a prospect in the world, in spite of the maunderings by Beau and his lodgers about expectations, or some such rubbish. Er… Mr Hartington experienced a vivid vision of Sid with a neat little aproned wife on his arm, and a neat little family at his knee, and blenched. What in God’s name would that do to Roland Lefayne’s reputation with his adoring public?

If he himself were not Sid’s manager, of course it would not be his worry—but what chance was there of giving it up? With all his capital sunk in the company… Um, suppose he sold out, perhaps to Sid backed by his wealthy brother, as indeed Sid had at one stage suggested… How much could he hope to get? Well, there was the name… But unfortunately, what kept Hartington’s Players afloat was the reputation of Roland Lefayne. If Sid were to take over the company, he could very well point out that he himself was its greatest asset and that without him, it was worth… Well, frankly, very little. There were the props and costumes, and a few scripts which Mr Hartington owned, mostly of melodramatic rubbish. And several actors’ contracts, but they weren’t exclusive contracts, because to offer those, you had to be sure of having the engagements. He did own the waggons, but they weren’t worth much. Damnation.

Moodily Mr Hartington wandered over to the window, twitched the curtain aside, and stared out into the darkness of dozing Dorchester. Would it run to, say, a nice little lodging house like this one, only by the sea? No it wouldn’t, except maybe in the tiniest of coastal towns. If only one had a cuddly little widow by one’s side, what could contribute to the price of the lodging house, then one could run a really nice establishment, in a pleasant town, and afford a cook and so forth. But in a tiny place, would one get sufficient lodgers? No. He sighed heavily. Damnation.

“Charmed, I’m sure,” said Sid on a sardonic note as Mr Vanburgh, having turned up at his hotel room at a very early hour, then proposed inviting himself to break his fast at his, Sid’s, expense. “Oh, go on then. Ring and ask ’em to bring it up here.”

Mr Vanburgh doing so, breakfast duly appeared.

“You would get as good or better at Mrs Fairweather’s, y’know, Sid. Or even at Ma Jellybelly’s, with Dinwoody and the lads!” he said with a chuckle.

“Jewbelly or some such, ain’t it? No, well, just for once, I thought I’d be comfortable in a decent hotel, where I can call my soul my own. Or such,” he said, looking hard at his visitor, “was my thought.”

“Aye.” Mr Vanburgh spread butter lavishly on a roll, added a huge slice of juicy ham to it, and bit into it. “Mm!” he approved through it.

Sid sighed, but took a roll. “They bake them in their own kitchens,” he murmured.

Mr Vanburgh nodded round his.

It was not until the rolls had all vanished, as had the fried eggs, the ham, and a large dish of blackcurrant preserve which Sid declared to be as good as his mother's had been in his boyhood, that the comic actor broached the subject which had been occupying his mind. “Sid, you do know that this is Lord Sare’s county?”

“Mm? Oh—s’pose it is, aye.”

“Er—look, I know not what your intentions may be, but since the venture to Miss Martin’s cousins fell through, don’t you think she should try the effect of that letter of hers? Go and see Lord Sare?”

Sid raised his eyebrows very high and drawled: “Is he in residence, Vic?”

“Yes, he is, and don’t play off them tricks on me! –Yes, the bobbing Miss Spink and the relentlessly twinkling Paffey at our lodgings reported that he was driving about the town in a curricle and four only yesterday, patronising the local tradespeople.”

“In every sense of the word?” he murmured, sharing the last of the coffee scrupulously between them.

“Thanks. Uh—well, no, I didn't get that impression at all. Paffey seemed favourably impressed. Bobby Spink didn’t see him herself, of course, but the tailor reported that he was a true gentleman. Which if he was one of your usual high-in-the-instep care-for-nobodies of that class, I don’t think he would.”

“No.”

“So shouldn’t Miss Martin be encouraged to use that letter? She shouldn't be jaunting round the countryside with Hartington’s Players if she’s a lady, Sid,” he said uneasily.

“If you are so concerned, Vic, I suggest you put it to her.”

“Well, I might, if you cannot damn’ well be bothered!”

Sid bit his lip. “I thought— No, I suppose I didn’t really think, Vic,” he said with a sigh. “I just had it in my head that it would be pleasant to let her… play the summer out,” he finished in a low voice.

Heavily Mr Vanburgh owned: “I suppose I see.”

“Mm, I suppose you do,” said Roland Lefayne with a wry little smile. “Um, well, I’ll have a word with her. Er, look, Vic, did you ever notice anything strange about Peebles?”

Mr Vanburgh gaped at him. “Peebles?”

“Mm.”

“Strange in what way?” he said limply.

“Any way.”

“Uh—you mean, anything out of character, that sort of thing? Um… We-ell, the episode of Beau’s damned flagstones? Present company were snoring in our pits at the time Peebles rode gallantly to the rescue on his charger,” he reminded him.

“I remember it, yes,” said Sid neutrally. “So?”

“Well, any man may be excused for coming the knight-errant in defence of his lady fair.”

“Yes,” he said flatly.

The wind somewhat taken out of his sails, Mr Vanburgh swallowed. “Aye. Um, well, as I was saying, the fact that he wanted to do it, says nothing. But… The fact that he could, did strike me as a little odd. A little clerk, lived the last twenty or thirty years in grey old London town… Granted his is a relatively active occupation. But to shift those damned flags? A man would have to be damned fit. Actually,” he said, coughing, “Daniel and I had been on the rum, one evening, and we wandered out to the yard and—uh, had a go at lifting the damned things. For my part, it was all I could do to drag one off its pile,” he said with a grimace.

“That does not altogether surprise me. –No offence meant, Vic. You called Peebles a little clerk, just then; well, I have used the phrase myself. But he was not, when you looked at him. He was certainly as tall as I am.”

“No, well, Lilian went on about his shoulders enough!” he said with a laugh.

“So did Cook,” agreed Sid drily. “I’ve been thinking about how I played the lawyer’s clerk for the visit to the Horse Guards. Come and look.” He went over to the cheval mirror but did not look in it, instead turned to Mr Vanburgh and said humbly: “H’if you will overlook my presumption, Mr Vanburgh, sir, I should like to give you a demonstration, what we call it in the law.” He turned slowly to the mirror; Mr Vanburgh’s eyes followed his. “The demonstration will follow in a moment, sir, h’if I may just be permitted to devoid myself of these documents first, or, as we say in the law, a priori.”

“Not ‘devoid’!” protested Mr Vanburgh. “Peebles was not a Mrs Malaprop!”

“No, he was far too subtle for that,” he murmured in his own voice. “Watch.”

Mr Vanburgh watched. The slightly stooped, humble figure in the glass straightened. It took a deep breath. The shoulders went back, the chest lost its hollow look, and the handsome face of Roland Lefayne smiled at the comic. “See?” he said.

“By God…” said Mr Vanburgh slowly.

“Want to try it?”

“N— Uh, you’ve a damn’ sight better pair of shoulders than I, Sid.”

“So,” he said drily, “had Peebles.”

“By God,” repeated Mr Vanburgh.

“Didn’t realise myself what I was doing until I stood in front of the mirror,” said Sid, returning to the table and flinging himself carelessly onto a chair. “Then I saw that he was doing it, too.”

“I feel the most complete fool. Hell, it is our profession!”

“Mm, well, we haven’t proven anything,” he murmured.

“Not damned half!” retorted Mr Vanburgh vigorously. He stood before the mirror, and muttering: “Peebles—normal; Peebles—normal;” tried the trick with the chest and shoulders for himself.

“See?” said Sid mildly. “I don’t know about you, but I think my craft must be largely instinctive. I just think to myself ‘humble lawyer’s clerk’, and find I am doing it.”

“I usually do it first instinctively, then I look at it carefully… Hell, I actually use the mirror, Sid,” said Mr Vanburgh in a stunned voice.

“Mm.”

“It never dawned that Peebles—”

“No, well, as I say, nothing is proven.”

Ignoring that, Mr Vanburgh returned to the table and said tensely: “Did you notice anything else odd?”

“Did you, Vic?” he replied on a mocking note.

After a moment Mr Vanburgh went very red. “That time he tore a strip off us… Um, well, actually I didn’t notice anything at the time. Only, looking back…”

“By all accounts he was not Peebles the downtrodden clerk. –Play it yourself,” he suggested.

Mr Vanburgh thought it over. “Look,” he said eventually, licking his lips, “I wouldn’t do it like that at all!”

“No. Well, I wasn’t there, but I think Lilian used a phrase like ‘chillingly icy’?”

“Quite. I think I’d… Well, I’d work myself up, y’know? Lose my temper, and work in a bit of stuttering and stammering. I’d tear a strip off, all right, but not like that. But,” he said with a moue, “do that merely prove that real-life characters are more complicated than we poor players are wont to assume?”

“Vic, you’re one of the best character actors I have ever seen,” said Mr Lefayne flatly.

“Thanks,” he said in surprise, reddening a little.

“I must say, I’d play it the same as you… I wish I had seen it,” he said, frowning.

“Er—well, yes, I think I wish you had, too, Sid. It’s hard to judge a performance when one’s own emotions are involved.”

Sid’s jaw hardened. “That reflection must have been a comfort to him, afterwards.”

“Y— Um, look, is not this all in our imaginations? Peebles, a—an impostor?” he said with a protesting laugh. “Why, in God’s name?”

“Why, indeed?” Carefully Mr Lefayne went through the arguments he had used with Miss Martin.

“He cannot have been set on to do her harm: his every concern was to keep her safe!” declared the comic actor when he’d finished.

“I agree, Vic. There are two other odd things of which you should be aware. First, Miss Martin has concluded, and I rather think her reasoning is correct, that the ubiquitous Dinwoody was set on by person or persons unknown to guard her while she was down in Devon.” He went over this in some detail, finishing: “Her conclusion was that as the unknown could not possibly be Peebles, it must be yours truly.” He raised a mobile eyebrow at him. “Flattering. Though the deciding point seemed to be that I was the only person at Beau’s with enough gelt to pay the fellow.”

“Have you taxed Dinwoody with it?”

“Both Miss Martin and I have broached the subject, and he has managed to skirt round it or give noncommittal answers to us both.”

“I see…,” said Mr Vanburgh slowly. “But a clerk could not afford— Oh.”

Mr Lefayne eyed him mockingly. “Quite.”

“My head’s getting muddled, Sid,” he said, rubbing it. “One, Peebles is an impostor, possibly put on by that General Toffee-Nose to look after Miss Martin; two, Dinwoody is another impostor, put on by Peebles to ditto?”

“Mm.”

“But why?”

“That is the mystery, Vic.”

Mr Vanburgh just nodded weakly.

“Um… did you see anybody at Quysterse that looked like Peebles?” demanded Mr Lefayne out of the blue.

“What— No. At Quysterse? Lord Hartwell’s place? No!”

“I did. First, when Miss Martin and I were strolling in the gardens. He came past with a group of people. Well, I say ‘he’: a man with Peebles’s profile. Lovely nose: did you ever remark it?”

“I suppose he did have, yes,” he said limply. “Are you sure?”

“I am sure it was the nose, yes. That it was Peebles—no. Miss Martin herself remarked that the carriage and the gait were very unlike his.” He eyed him a trifle mockingly.

“Oh,” said Mr Vanburgh slowly, looking at the mirror.

“Quite. Then, during the show, there was a fellow in the audience in the front row—Twelfth Night, this was. Spent most of the show with a handkerchief over his face. Did you spot anything, when you were on as Malvolio?”

“N— Hang on. When I first came on, there was a fellow that was asleep. But then I think he vanished. I never saw his face at all.”

Sid shrugged. “Could mean anything or nothing. I looked for him afterwards, during the party, and then when they asked me to stay on at the house. Not a sign.”

“Oh? Um—well, there were crowds there, from the neighbourhood, and so forth. I dare say he vanished with the rest.”

“Yes. That is certainly the logical assumption.”

“Is there a but?” said Mr Vanburgh limply.

“Not really. Well, if the rest sounds a trifle mad, in that we have found no possible motive, but in practical essentials quite feasible, this must sound wholly mad! And I would never even have noticed it, but for the connection already suggested by Miss Martin’s letter.” Mr Vanburgh was staring at him: Sid licked his lips and admitted: “The only fellow of the house party to vanish without warning was Viscount Hartwell’s maternal uncle.” He looked at him apologetically. “Lord Sare.”

“Sid, that truly is mad,” said Mr Vanburgh in a shaken voice.

“Yes, I thought so, too. Er—Harold accuses me of having too intricate a mind,” he murmured.

“You haven’t told him any of this? –Good,” he said in relief as Sid shook his head. “He’s got enough on his plate with the tour. –Sid, Lord Sare cannot possibly be involved! I mean, for God’s sake, Bobby Spink and Noddy Norton tell me he owns half of the county!”

“Who? Oh, the odd-bodies at your lodgings!” said Sid with a laugh. “Well, I concede I cannot think why he should be involved, and it is doubtless just a coincidence—though Lady Hartwell was very miffed that he should vanish like that, when it was his niece’s birthday. Um, well, I can think of half a dozen explanations, actually,” he admitted with his glinting smile, “but—”

“Spare me,” groaned Mr Vanburgh, holding his head.

“—but I shall spare you, because they are fit only for melodrama!” he ended gaily.

Mr Vanburgh grinned at him. “Good.”

Sid stood up, and stretched. “I must have my bath.”

Mr Vanburgh just sat limply in his chair and waited, as Sid ordered his bath water, took his bath, was shaved, and got into his clothes. “We’re late,” he noted feebly as Sid finally picked up his hat.

“How dreadful. Will Harold be cross?”

“Mm. He’s brooding because of the lack of available widows.”

“Thought there was one?”

“The foreign lady? Coolly friendly. Don’t think he knows what to do in them circumstances, Sid,” he said meanly.

Sid sniggered, and took his arm, and the two went downstairs together. Vic Vanburgh, to say truth, felt in need of the supporting arm. His head was spinning.

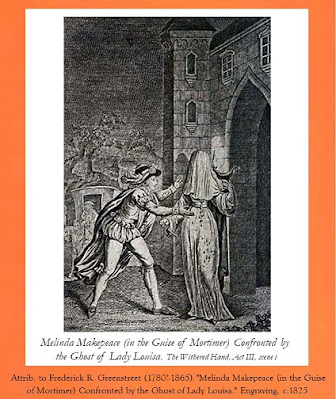

All In The Mind was very well received by the genteel persons of Dorchester; and the gods laughed themselves sick over one particular scene which, according to his company, Mr Hartington was wont to overplay; so that was all right. It certainly augured well for the rest of the season. And the players had best hurry up and learn their lines for the Hand.

“Miss Martingale,” said Mr Hartington terribly, discovering the lacunae in her knowledge of the Lady Louisa, “this will not do!”

“It's Mrs Warburton, sir, she don’t never give us ’ardly a chance to study our lines!” chirped Georgy helpfully.

“Silence,” he said awfully. “Is this true?” he demanded sternly of his apprentice.

“Well, yes,” she owned glumly. “She comes in and chats, sir, the moment one of us is alone with a script.”

“Right. Get round to Mrs Fairweather’s, tell her I sent you, and ask to use the parlour. There won’t be no-one there, at this time of day; well, possibly the foreign lady, but she won’t bother you. –You, too,” he ordered Tilda. “Not YOU!” he shouted terribly as Georgy bounced up. “Timmy hasn’t got but a bare page, and I’ll hear you myself. –Go on, what are you waiting for?” he said to his ingénues.

Gulping, the girls gathered up their scripts and vanished.

The door of the handsome, narrow modern house which featured a pleasant bay window overlooking a tiny garden which held a plot of grass and one leafy tree, reported by Mr Deane to be a cherry tree, was opened by a small, neat maid, considerably younger than they themselves. “Good morning, Misses. Can I help you?” she piped, bobbing.

“Yes—er—we have been sent by Mr Hartington. We are with his theatrical company,” said Miss Martingale, having taken a deep breath, “and we would like to speak to Mrs Fairweather, if she is in.”

“H’actresses!” she gulped, her eyes going round as saucers.

“Er—yes. Is Mrs Fairweather in?”

“Yes, Miss—ma’am! I’ll get ’er!” she gasped, disappearing.

They waited a few moments, and then a smiling, plump, red-cheeked woman in a spotless white cap and apron over a neat black gown appeared. She appeared to take it as quite natural that Mr Hartington had dispatched two young actresses to sit in his landlady’s parlour and learn their lines, and showed them into it. And offered them a cup of tea.

Cups of tea were usually the precursor to prolonged chats, at Mrs Warburton’s. Miss Martingale and Miss Trueblood exchanged a cautious glance.

“After which, I’ll leave you to learn up your words, my dears!” said the motherly landlady with a chuckle. “And no-one won't disturb you, except Mrs Anstey, she might come in here and study her book.”

“Thank you so much, Mrs Fairweather. We should be very glad of the tea,” said Miss Martingale, since Miss Trueblood did not seem capable of speech.

Smiling and nodding, Mrs Fairweather went out, and the two girls sat down limply.

Half an hour later, when Mrs Anstey came in quietly with her book, the chestnut head and the brown were bent studiously over the scripts.

“Please, do not get up,” she said with her pleasant smile. “Mrs Fairweather has said there are two young ladies in here. I shall not disturb you.”

Although her English was excellent, there was a definite Dutch accent; Major Martin’s daughter could not help but stare, a little. But she said politely: “Thank you, ma’am. I fear it is rather we who may disturb you.”

“You vill hear each other recite, n’est-ce pas? That vill not disturb me,” she said, smiling. “I shall enjoy it.”

“Thank you, ma’am!” gulped Tilda.

And with that they all settled down to their reading.

“Do you think you have it?” said the Lady Louisa at last.

The heroine of The Withered Hand looked anxiously at Mrs Anstey, but that lady appeared unaware of them. “Um—yes. Um—well—shall we?”

“Yes. You can hear me first, if you like.,”

After some time of it, Mrs Anstey emitted a gurgle of laughter. “I do beg your pardons!” she gasped. “May I ask, vhat is it?”

Smiling, Miss Martingale returned: “It’s a very silly melodrama in the Gothick style, ma’am, written by an unknown, whom we suspect is our manager Mr Hartington himself, and entitled The Withered Hand, or, The Fate of Crestingforthe Castle. All predictions are that it will be a tremendous hit in Dorchester!”

“Yes? So, Mr Hartington is an author as vell?” she said with smiling interest.

“Yes, ma’am: he writes a lot. And sews as well as any woman,” volunteered Tilda, very flushed.

Mrs Anstey’s eyes twinkled but she merely returned politely: “I see.”

After considerable hearing of the lines on both parts, Mrs Anstey put down her book and said: “I think there is a scene there vhere you both play, no? Vould you care for me to hear that for you? It vill be very good for my English!” she added with a little laugh.

The girls accepted gratefully, and Mrs Anstey duly heard their lines in the scene where Melinda Makepeace encountered the gauze-draped Lady Louisa—moaning. She was quite intrigued that the pretty little chestnut-haired girl did not do the moans, but only said: “Moan, moan”; and eventually enquired politely why this was so.

“Well, this is just a reading for words, ma’am,” said Miss Martingale, twinkling at her. “One does not do the effects, you see. Those who do so are regarded as rank amateurs by the acting profession!”

Mrs Anstey then asked, very politely, if they would do the scene properly: she would so love to hear it. Adding: “Mrs Fairweather and Jessie Sharp are in, and I think a Madame Beet, who helps to scrub. Perhaps they might listen, also?”

The young actresses assenting to this, forthwith Mrs Anstey rang the bell. And soon Mrs Fairweather, Miss Sharp and Mrs Beet were all seated in an expectant row.

The scene was greeted with gasps, squawks, shudders and clutching, and finally, by ecstatic applause. After which Mrs Fairweather insisted the girls stay for the midday meal. Which was usually not very fancy, she explained comfortably, for her lodgers mostly didn’t manage to get back from their work for it.

It was fancy enough: a huge cold ham, cold spiced beef, innumerable relishes and pickles, a giant dish of hot boiled potatoes and another giant dish of hot buttered beans, and a green salad with a positively miraculous sauce. Followed by a concoction which the modest Mrs Fairweather described as “just a fruit shortcake” and which featured currants and raspberries, accompanied by clotted cream. An elderly Mr Nickles who had come in for the feast from “just down the road a bit,” and who apparently habitually did so, owned that it was “something like” and he would wager the young ladies had never ate so well in their lives. A sentiment with which no-one felt inclined to argue.

Then they had to make a dash back to the theatre, for there was a performance of All In The Mind this afternoon. If Tilda’s portrayal of Angelica Addle was somewhat sluggish, the Dorchester audience noticed nothing amiss.

After a shouting match between Mr Lefayne and Mr Hartington on the subject of whether or not an extra show would, could or should be fitted in on the Wednesday afternoon before the first night of The Withered Hand, Mr Hartington conceded that everyone could have a rest. He himself returned, therefore, to Mrs Fairweather’s early in the afternoon. Daniel and Vic seemed to think that an afternoon off meant they could go and carouse in some damned tavern that Daniel claimed served the best brandy he had ever tasted—well, let them, and if they turned up blind drunk this evening they would NEVER PLAY FOR HIM AGAIN!

The parlour was occupied only by the blonde Mrs Anstey, quietly reading her book. She greeted him politely.

“Afternoon, ma’am,” replied Mr Hartington grumpily, sitting down.

Mrs Anstey smiled a little. “Have you eaten, Mr Hartington?”

“It cannot signify,” returned Harold sourly.

“Mrs Fairweather vill be only to happy to offer you a collation, sir. May I ring for Jessie Sharp?” she said politely.

“Oh, go on, then. –Thank you,” he added lamely.

Jessie Sharp duly presented herself, and in no time at all Mrs Fairweather had a little table at Mr Hartington’s elbow, laden with mounds of sliced, cold spiced beef and juicy ham, crusty fresh rolls, fresh butter, a great selection of relishes and a tankard of ale.

Mrs Anstey read her book quietly, glancing up now and then with a tiny smile, as Mr Hartington ate ravenously. “She is an excellent cook, no?” she murmured as finally he patted his mouth, removed his napkin from under his chin, and sat back with a sigh.

“I’d marry her tomorrow if it weren’t for Fairweather!” admitted Harold incautiously.

She gave a startled laugh, but nodded, and noted: “I think you vould have to beat off first Mr Nickles from the road and then Mr Norton and Mr Paffey!”

He grinned sheepishly. “I’m sure. Er, believe you heard my girls’ lines t’other day? Thank you kindly, ma’am.”

“It was my pleasure; and then, you know, they gave a little performance for myself and Mrs Fairweather and the maids,” she said with a smile.

This detail had not been imparted to the girls’ manager: he winced, but nodded.

“Mr Hartington, I vonder if I might ask you a favour? I am trying to improve my English. Could Miss Martingale spare the time to help me with it? For a small payment, of course.”

He blinked. “Er, well, your English is excellent, ma’am. Um—she never grew up in England, herself, y’know,” he said uneasily.

“No: Holland, I think?” said Mrs Anstey composedly. “That is vhy I think she could help me.”

“Aye. Well, I’ve no objection, so long as it don’t cut into her working hours. Let me see.” He withdrew a wad of papers from a capacious pocket. “Saturday morning, she’s free until one: they tell me it’s market day, so we won’t put on a morning show. But she’s got an afternoon performance of Two Belles And A Beau, and in the evening it’s the Hand. And I want to run through Twelfth Night on Sunday—”

“Oh, you are doing Shakespeare?” said Mrs Anstey pleasedly.

“One performance only, for Dorchester, ma’am,” he said severely.

“But I should so like to come! For it is so educational, as well as so English, n’est-ce pas?”

Mr Hartington blinked, but conceded: “Aye. Well, that’s on the Monday evening, ma’am. We have a fair few bookings, but there’s still plenty of seats available. Let’s see… You can have her on the Sunday. How much were you envisaging paying her, ma’am?” he added cautiously.

Mrs Anstey named an hourly sum. Mr Hartington scarce forbore to gulp: he himself would have not paid half that for someone to help him with a foreign language. He agreed to it, however, and promised to tell Miss Martingale.

She thanked him politely. Mr Hartington swallowed a sigh. Them blonde good-looks were really something, and she had just the sort of full figure he liked. But that cool, ladylike don’t-touch-me stuff was more than he, Harold Hartington, could cope with.

… “Really? For money?” cried Miss Martingale.

“Er—yes,” said Mr Hartington. “Dunno why, for her English is excellent. Um, well, Paffey said she was struggling with her book, t’other evening. Maybe she don’t read it so well. Anyway, she wants you, because she thinks you’ll be able to help her, having grown up with Dutch speakers.”

“I knew she was Dutch!” she said with a laugh.

“Aye: damn’ funny accent, ain’t it? Um, hang on. What do you mean?”

“What do you mean, sir?” replied Miss Martingale in bewilderment.

Mr Hartington scratched his head. “Maybe I got it wrong. She wanted you, because she knew you grew up in Holland.”

“What? But I did not mention it, sir!” she said in astonishment.

“Nor did I. Oh, well, dare say Vic or Daniel must’ve. That’s it, then. I’ve writ down for you when you may go.”

“Thank you so much, Mr Hartington!” she beamed.

“Not at all,” said Mr Hartington with a sigh.

“What’s the matter, sir?” asked Miss Martingale shyly.

“Nothing. Well, Mrs A. is a fine figure of a woman, but a lady, if you know what I mean. Friendly but cool,” he said, scowling.

“Oh,” she said, biting her lip. “That need not mean she does not like you,” she ventured.

“Actually I think possibly she does like me, but as a duchess might condescend to like a butcher. Not for an instant considering him as a man,” he said grimly. “The player’s lot.”

She looked at him distressfully but could think of nothing to say to comfort him.

“Go on,” he said with a sigh. “Run along. Oh, and tell Tilda plenty of rouge, tonight: the place is a blaze of lights, we don’t want them to think she’s a second ghost.”

Smiling gratefully, Miss Martingale escaped.

The Withered Hand, or, the Fate of Crestingforthe Castle was greeted rapturously—there was no other word—rapturously—by Dorchester.

“To be expected,” noted Mr Vanburgh, who was not in it, and had been made to prompt. “No, well, congratulations, Harold!” he said with a laugh.

“Vic, if this were Drury Lane, we would putting on three pieces worthy of your talents,” said his manager heavily.

“I know that, old man! –My favourite bit was where young Georgy accidentally trod on the Hand’s toe, and Sam gasped. Though I dare say no-one beyond the first five rows heard him.”

“Really?” he said evilly. “For myself, I preferred the bit where damned Daniel made as if to shake the Hand as it emerged from the painting, and if he does it again, I’LL STRANGLE HIM WITH MY BARE HANDS!”

“No pun intended, one presumes,” said Mr Vanburgh sadly, as, breathing fire and brimstone, Mr Hartington strode off in the direction of Mr Deane’s dressing-room.

Nevertheless, Dorchester had greeted the Hand with rapture, and its creator silently made up his mind he would cut back on the Molière in the small towns and villages in its favour. And if only Sid would hurry up and finish that thing he was scratching out, which he claimed was also a melodrama, they might try it in one of the smaller towns, to see if it would do for the rather larger centres.

Mrs Anstey’s lessons with Miss Martingale duly began. Very soon the teacher realised dazedly that although her pupil had an excellent ear, and spoke French even better than she did English, she had scarce any knowledge of the rules of grammar—in any language. Her written Dutch was barely passable, and her written French at about the level of a child of ten. Not a French child. Mrs Anstey herself was quite frank about all this, and very grateful to have Miss Martingale help her. It was now clear, too, that, Mr Hartington’s claims to the contrary, and however ladylike her manner, Mrs Anstey could scarcely be from the genteel classes. Her Dutch was the sort that the Martin family had been accustomed to hear in the street markets at home, and scarcely reached the standard that Mevrouw Hos considered passable.

It was all very odd, but Major Martin’s daughter politely refrained from giving the appearance of being at all curious. And, what with concentrating on this, and on correcting the Dutchwoman’s grammar in both English and French, did not perceive that Mrs Anstey had begun to experience not a little curiosity about herself, and her own evident grasp of the Dutch demotic.

“Well!” she said to Troilus as they walked back to Mrs Warburton’s for their midday meal through the warm quiet of a dozing Dorchester Sunday. “Mrs Anstey is not a lady after all! Should I tell dear Mr Hartington? …No,” she said regretfully. “It might not be safe; well, certainly not for us, Troilus, for one never knows, n’est-ce pas, petit toto? And if she is here to establish herself as a lady, she will not care for anyone to know she is not. But what a pity. She is so very pleasant. Not at all the type of that horrid Mrs Greatorex!”

Troilus’s little tail wagged busily. This might have been because he was investigating a laurel bush which indicated that its owner also owned a cat; but his mistress took it as agreement.

Miss Martingale was a little late returning to Mrs Fairweather’s to resume the lesson, for her meal had been followed by an altercation with Georgy over who should have charge of Troilus this afternoon, which had had to be settled by Mrs Warburton in person. She did not, therefore, expect to see any of the theatricals there, except perhaps Mr Deane, who was not in Twelfth Night; and so was somewhat startled to have the front door opened to her by Mr Vanburgh.

“Good afternoon, sir; will you not be late for rehearsal?” she said politely.

“No, Harold’s told me to turn up later: he intends first rehearsing those who may be expected to have forgotten their parts since we last did it.” Mr Vanburgh emerged onto the step, pulling the door to behind him. “We’ve got a visitor,” he said in an odd tone. “Not expecting anyone, were you?”

“I? No, indeed. –Help!” she gasped, clutching his arm. “Not one of the Dearborns?”

“Oh, Lord, no. Sorry, my dear,” said Mr Vanburgh remorsefully, seeing she had gone very white. “Nothing like that at all. Come along in.”

Very puzzled, she followed him in and allowed him to show her into the parlour. Mrs Anstey was in there, chatting politely to—

“Mr Peebles!” she gasped, going very pink.

The lawyer’s clerk, looking his usual meek self, rose and bowed. “Good afternoon, Miss.”

“How are you?” she returned very limply indeed, holding out her hand to him.

“Keeping very well, thank you, Miss. Down here with urgent documents what would brook no delay,” he said, taking the hand and bowing over it.

“Going back, or so he tells us,” said Mr Vanburgh neutrally, “on tomorrow’s stage.”

“The Salisbury stage, Miss. It leaves first thing. For there are documents which were not so urgent, only it was deemed more convenient to drop them orf.”

“Since he was down this way,” explained Mr Vanburgh neutrally. “Doing so will probably necessitate his spending a night upon the road which he would not have, otherwise, but what is that to a firm of London lawyers?”

“Oh, quite, Mr Vanburgh,” he said in a puzzled voice.

“Salisbury is a pretty town, I think?” said Mrs Anstey politely into the sudden silence.

“Why, yes, ma’am!” Mr Peebles agreed. “A cathedral town, and said by them as knows to be one of the most memorial religious structures in England.”

Mr Vanburgh lounged over to lean an elbow on the mantelpiece. “Tall, is it?” he said in a sardonic tone.

“Tall and gracious, Mr Vanburgh, sir,” replied Mr Peebles, giving him a puzzled look.

Miss Martingale also gave Mr Vanburgh a puzzled look: he was, normally, a quietly polite and kindly-natured person. Why was he needling—yes, positively needling—Mr Peebles in this fashion? “Um—but how did you find us, Mr Peebles?” she said with a smile.

“Dorchester,” said Mr Vanburgh, more sardonic than ever, “is not so very large.”

“No, well, not compared to London, out of course,” said the clerk respectfully. “But a fair-sized centre. I customarily stay with Mrs Fairweather when I stop over here, Miss.”

“A remarkable coincidence,” said Mr Vanburgh smoothly.

“Well, yes!” she agreed, somewhat desperately. “Though I am not surprised to hear that having once chosen to stop here, you should make it your custom, Mr Peebles. The players have been made very comfortable indeed. Which indeed we all have, and the consensus is, that the Dorchester landladies are the best in the country!” she finished with a twinkle.

“That is my h’experience, also, h’if I may make so bold,” agreed the clerk. “But I must not intrude upon your lesson, Miss, and will get out of your road, direct.”

“You vill not be in our road, sir, if you care to stay in the parlour,” said Mrs Anstey politely. “Vill he, Miss Martingale?”

“No, of course, Mr Peebles.”

Mr Peebles, however, though bowing very much and professing himself most gratified, said that he would not intrude upon their privacy, and, reminding them that his father’s family hailed from these here parts, explained that he intended calling upon distant connections this afternoon. Having assured himself that Miss Martingale would still be here when he got back, for she had earlier accepted an invitation to eat Mrs Fairweather’s definition of “just a cold supper,” he eventually got himself out of the room.

“An edifying performance. I liked the touch of the distant relatives,” drawled Mr Vanburgh.

“Mr Vanburgh, what on earth is the matter with you?” demanded Miss Martingale baldly.

“Nothing in the world. I’ll get out of your road, too, ladies. Sid has produced a great sheaf of scribbling which he wants me to run my eye over, so I might as well. Er, may I ask you, Miss Martingale, if I don’t reappear by three-thirty, to run upstairs and batter on my door? Number 3, on the first floor. Too much luncheon and a warm afternoon may combine against the stimulation to be expected from a little melodrama dashed off between performances!” He bowed, twinkling, and was gone.

After a moment Mrs Anstey said slowly: “May I beg you to say, my dear, vhich vas the true Mr Vanburgh?”

Miss Martingale swallowed. “How acute you are, ma’am. He—he is a very complex personality. A wonderful character actor, of much subtlety. Um, both, I fear,” she admitted, biting her lip a little. “Though I have never before seen him needle a person in quite the way he did poor Mr Peebles, just then.”

Mrs Anstey nodded slowly, but merely said: “Alors: recommençons?”

And they got on with the lesson.

“I grant you the sudden stress on the existence of relatives, however distant, is suspect, Vic,” agreed Sid lightly. “Though he always did claim his family was from these parts.”

“Yes, but why suddenly introduce it at this juncture?” said Mr Vanburgh heatedly.

“Mmm… Could be a coincidence.” Sid thought it over. “I will come back to supper,” he agreed.

“Good,” said Mr Vanburgh, sagging.

“Anything else suspicious about him? Accent? Mode of expression?”

“No,” said Mr Vanburgh reluctantly. “Um, well, he called Salisbury Cathedral a memorial religious structure. Don’t think we ever heard him play the rôle of Malaprop, hitherto?”

“Unlike Margery—quite. Have you met her landlady?” Mr Vanburgh shook his head, looking puzzled, and Sid explained with laugh and a shudder: “Even worse! More refeened, too! Could barely keep me countenance! Um, no, well, if Peebles meant ‘memorable’… Hm.”

“I thought it struck a false note.”

The leading man nodded slowly. “What else? How did he seem with Miss Martingale? Tongue-tied?”

“No-o… Well, once one had got him going he was always loquacious enough, wasn’t he? He wasn’t tongue-tied, but very little to the point: same as usual, in fact. I thought, actually, that if either of them found themselves with little to say, it was she.”

“Or was it that she was disappointed in what he did say?” said Sid Bottomley lightly.

Vic Vanburgh gave him a sympathetic look. “Well, seeing a man after something like three months, then he bores on about his damned urgent documents, same as usual… Um, I did wonder if he was sustaining the part too well. And if a normal man might have shown a damned sight more flutter than he did. Or am I being over-nice?”

“Harold would certainly claim as much! No, well, seeing her in company, Vic,” he reminded him.

“Yes. Well, I suppose it proves nothing, one way or t’other. –I tried needling him, y’know, but he was Peebles to the life. Had to admire him for it,” he said, shaking his head.

“Shall we try not needling him, this evening, and merely observing?” he said, the thickly-fringed grey eyes sparkling.

“Right you are,” agreed Mr Vanburgh with a grin.

They tried. Peebles was no different from the Peebles they had always known—when allowed to speak, which given that Mr Hartington, Mr Fairweather, Noddy Norton, Bobby Spink and Twinkles Paffey were also present at the board, and all considerably cheered by the administering of Mr Fairweather’s customary nectars, was not often.

He did not offer to escort Miss Martingale back to her lodgings after supper, even though Mr Lefayne deliberately hung back himself in order to allow him to do so. Which, again, might have proved that he was sustaining the rôle too well, or merely that he was the self-effacing Peebles of old. There were no further malapropisms, either. Which might have proved that the earlier one had been a mistake and that he had thought better of it, or that he had in fact been more fluttered by the meeting with Miss Martin than he had otherwise allowed to appear.

… “Damned inconclusive,” summarised Mr Lefayne drily the following day.

“Aye. But ain’t it too much of a coincidence, Sid?” said Mr Vanburgh crossly.

“You mean that he should have been sent to Dorchester at this precise moment, instead of, say, York, Manchester, Edinburgh, John o’ Groats…?” Mr Lefayne’s striking eyes narrowed. Eventually he said: “Given the earlier coincidence of his turning up in Bournemouth and having business in Devon just at the time Miss Martin was headed there… Yes. Most definitely too much of a coincidence, Vic.”

Mr Vanburgh nodded feelingly.

“But I still cannot make out why!” said Sid on an irritable note.

“Me, neither. Er—I managed to skim through the new piece, Sid,” he said cautiously.

“And?” returned its author, straight-faced.

Mr Vanburgh leant forward. “Sid, if only we could do it in front of him!”

“Aye,” he said with a wink. “‘The play’s the thing’, eh?”

The comic actor nodded feelingly.

“Mm. Too much to hope for,” said Sid with a sniff. “Well, never mind, it will do for these south-coast towns.”

“Mm. So, writing out the plot did not clarify matters for you?”

“No more than seeing Peebles in person again did, no, Vic!” he said with a laugh and a shrug.

Mr Vanburgh sighed, and nodded.

Possibly the mystery might have been clarified a little for the actors could they have been present in the ancient Duck and Plover at a very early hour on the following day.

Mr Peebles was discovered placidly drinking coffee. “Morning, Dinwoody,” he said unemotionally.

Mr Dinwoody sat down. “Thought you was supposed to be on the Salisbury stage?”

“Yes, well, I am certainly not at Fairweather’s,” he replied mildly.

“No, and you better not be here too often, neither, acos Daniel Deane, he’s discovered the place has the best brandy in Dorchester!”

“It will not have for too much longer, since Dupont’s vanished, and our source of supply may be said to have dried up. But I take your point.”

Mr Dinwoody scratched his blue chin. “How reliable is this Bernie Bamwell?”

“Well, he drinks the stuff, Dinwoody!” he said with a laugh. “Oh, well, as reliable as most of the gentry, I make no doubt,” he admitted on an ironic note. “But in this instance there seems no reason to doubt his word. He did sail over to Jersey. Added to which, Fairweather,” he said, eyeing him ironically, “has checked up on it for me.”

Mr Dinwoody counted on his fingers. “You get the initial report from Bogaert, if I mistake not—don’t bother to deny it; then Twin confirms it; then you lay off for a bit and it seems the report is right and Twin ain’t playing us false; then you get Bamwell to check up on Twin’s and Bogaert’s stories; then you send Fairweather over to check on them? I’d say you can be pretty well sure of it, aye!”

“Mm. Well, you know I am a cautious man,” he said primly.

Mr Dinwoody choked.

“And as His Majesty’s Excise has not descended in force upon either Melrose or Fairweather,” he murmured, “the probability is that Dupont has not informed upon us.”

“Well, that is good!” said Mr Dinwoody with huge sarcasm. “Otherwise, you might ’ave to come clean, Mr Smith, sir.”

“Oh, lud: and what would that do to my reputation around the clubs?” he said in mincing accents.

Mr Dinwoody, taken completely unawares, collapsed in horrible splutters, and the man who was very much not Peebles, meek lawyer’s clerk, grinned, and shouted: “HOY! MELROSE!”

A yawning Mr Melrose then presenting himself, a sustaining breakfast was ordered up. The landlord owning graciously, upon being pressed, that he didn’t mind if he did join them.

By the time the breakfast had vanished, and a beaming Mrs Melrose had been congratulated upon her cooking, it was long past the hour at which the Salisbury stage customarily departed. Of which Mr Dinwoody did not scruple to remind his companion.

“Very amusing.”

“Um, well, what’s next, sir?” he asked on a glum note.

“Oh—respectability, Dinwoody?” replied the other lightly.

“So it’s all over, then?” he said heavily.

“Not quite. You must see Miss Martin safely to Sowcot, and someone must persuade her to use that damned letter to old Neddy,” he said, frowning.

“Aye, well, think Mr Lefayne’ll do that. But if he don’t, I shall, never fear.”

“Good man. And the brother? Has he been behaving himself?”

“So far as I can ascertain, sir, like a h’angel. Which is suspicious in itself. And since I didn’t ’ave, sir, permission to follow ’im when ’e went orf—”

“That’ll do, Dinwoody,” drawled the man who was not Mr Peebles.

“Yes, sir! Beg pardon, sir!” he said, saluting smartly.

“Do not salute when we are both seated and I am out of uniform, you ape,” said the other calmly.

“Can’t ’elp it, sir, it’s me lower class iggerance,” returned the blue-chinned one insouciantly. “Um, well, to get back to our muttons, I haven’t a blamed notion where he went.”

“Well, I have,” he admitted, frowning. “At least for part of the time. For Peebles recently had occasion to deliver a document or two in Axminster, and got down to Sandy Bay. Where a red-headed gentleman what had shown himself most liberal-handed—highly suspicious, yes,” he said as Mr Dinwoody opened his mouth in amaze—“did stay for a night before, or so rumour had it, getting off to Dearborn House.”

Mr Dinwoody gulped.

“Though I do not anticipate a plot between himself and Dearborn, not to say Ma Dearborn, to eliminate Miss Martin, and share her part of the inheritance,” he said lightly. “For that young gentleman, from all I have heard of him, would be the very last to wish to share anything at all.”

“You’re right, there! He's cozened Hartington into giving him a damn’ good part in Lefayne’s new piece, what by rights that ineffective little Darlinghurst should have got, poor little fellow. Then, not content with that, he starts angling for Darlinghurst’s part in Twelfth Night as well! I didn’t say,” he said, eyeing him blandly, “why not cast Miss Martin as Viola and Amyes as Sebastian, for with the both in black wigs, they would be like as two peas in pod: for it might have give rise,” he said on a hugely ironic note, “to suspicion.”

“Mm. Well, the visit to Dearborn House may just have been a scouting expedition.”

“Yes. Um, lumme, Dearborn thinks it was him what got Miss Martin on out of it to Sare Park!” he remembered in dismay.

“I am very sure that Master Ricky was more than capable of countering that one.”

“Aye, well: quick on his feet, you could say,” agreed Mr Dinwoody sourly. “But don’t be surprised if Dearborn writes a letter to Sare Park!”

“Do he care enough to enquire?” he said with a shrug. “No, well, let’s bear that in mind, then. Er, talking of Master Ricky, has he shown any concern at all for his sister’s wellbeing? Or tried to talk her out of this acting thing—anything like that?”

Mr Dinwoody snorted. “’Im?”

“It sounds as if he is as worthless as the father, then.”

“Well, I’d say ’e was worse, for at least the late unlamented seems to have sent her to a nice school and took care of ’er, within ’is lights, till ’e went on the gin.”

“Quite. Er—thought it was brandy?”

“Both. She let it out to me only t’other day. We was talking of the Dutch lady, and somehow the topic come up. Said she cannot abide the smell of gin since.”

“Poor little soul,” he said with a sigh.

Mr Dinwoody hesitated. Then he leant forward and said: “Look, she is not a poor little soul at all. I grant you she has had a pretty hard life, at least for one born a lady. But she has come through very well, with all her wits about her, and is getting on famously in a very different sort of life from the one she knew in the past. She’s made friends, she’s shown herself not afraid of hard work, and she has sufficient talent and looks to make a success of the acting. I don’t say she might not succumb to Lefayne’s well-known, not to say well-worn, charms, in the end: but he’s fallen pretty hard; I’d say there’s no doubt he’d make an honest woman of her. Can you not leave it at that?”

The other hesitated. Then he said in a low voice: “I own, that was in my mind. But I can’t leave it, no. It is not her birthright. It would be entirely dishonourable to let it go on. I should never have let it get this far,” he said with a sigh. “I must end it.”

Mr Dinwoody looked cautiously round the dark, if commodious Duck and Plover. There had been only one other customer besides themselves at this early hour: a man who looked like a carter. At this moment he was seen to drain his tankard, and go out. Even Mr Melrose had disappeared from behind his bar. The blue-chinned Mr Dinwoody leaned even further over the table and put a hard hand on his companion’s long, slender one. “Very well, old man,” he said in a voice which was entirely unlike the tone he had used since the moment of encountering Mr Briggs, Miss Skate, Miss Martin and their travelling companions. “I am with you.”

The man who was most definitely not a lawyer’s clerk, but who was certainly the master-mind behind the smuggling ring that had been plaguing the coast of Dorset since well before our glorious victory at Waterloo, smiled rather sadly at him. “I know that. Thanks,” he said on a sigh.

Next chapter:

https://theoldchiphat.blogspot.com/2023/02/a-sowcot-welcome.html

No comments:

Post a Comment