13

The Actor’s Life

“You are NOT coming on with that dog!” announced Mr Hartington at his firmest.

Momentarily defeated, but far from crushed, Master Trueblood returned Troilus to the red-cheeked Miss Martingale, and took up his position again. The rehearsal continued.

“Read,” commanded Mr Hartington neutrally, having engulfed a cold pork pie and ordered “you boys” to “get on out of it and hear each other’s lines.”

Miss Martingale swallowed nervously, and did her best with the part of Jane, maidservant to Mr Addle, written as a sensible, hearty person of thirty-five summers at the very least.

“She did not envisage herself taking the part you had writ for Nancy,” noted Mr Vanburgh idly.

“You can get on out of it, too. Take that Paul Pouteney through his lines as Flush, and convince him he’ll be so made-up his mother wouldn’t know him, so there won’t be any point in fluttering the damned lashes.”

Shrugging, Mr Vanburgh liberated a large slice of fruit-cake and wandered out, munching.

“We’ll do this bit,” Mr Hartington decided, “where Jane comes in and pretends to hit her head. Go on, read.”

Miss Martingale did her best.

“No,” said Mr Hartington as she was replying limply to Mr Addle’s enquiry about the success of his latest drench. “She’s quite a lively gal, you see. Scoffs at him, if she is a maidservant.”

“Yes, I know. Very typical of Molière’s maids. But I don’t think I can do it.”

Mr Hartington did not appear put out to hear that Miss Martingale had recognised the source of his plot; he said pleasedly: “Ah! Read Molière, do you? Great man, is he not? Well, yes: Toinette, I mean Jane, is very typical. Apart from the brother, the only sensible character in the play. Put a bit more energy into her. Um… you must have had maids of your own, at home. Think of one of them.”

She did so, and gulped. “Yes, well, she was Dutch… She would certainly not have stood for any of his nonsense.”

“Good. Play it like her, then.”

This time Jane came over as a managing woman of forty-odd: one could positively see the apron and the arms akimbo.

“That’s better, but you’re too young for it, really. Not that a maid couldn’t be young, but she’s obviously been with him for years,” he said tolerantly.

Mrs Hetty had been sitting by quietly, eating pork pie and fruit-cake, and drinking a liquid of which she had refused to let Miss Cressida, Tilda or Georgy partake. Now she cried: “Give over, Harold, do! Let the girl read something prettier!”

“Pretty is not all there is to the stage life,” responded Mr Hartington solemnly.

“Ratsh. Give ’er Vi’a,” she said thickly through the cake.

He rose in a stately manner and removed the remains of the cake from under her nose. “Untried walk-ons do not play Shakespeare’s great heroines. But you can read it, if you like, my dear. Read the play, have you?”

“Yes, sir.”

“I won’t ask,” said Mr Hartington with a twinkle in his eye, “if you have imagined yourself in the part of Viola, because they all do. Go on, then: read.”

Gamely Miss Martingale began: “What country, friends, is this?”

Mr Hartington let her get right through the scene, not interrupting, even though she jumped in a most un-Viola-like way when Mr Speede answered her first line in the persona of the Captain.

“Yes,” he said heavily at the end of it.

“She read it very nice!” said Mrs Hetty indignantly.

“Very ladylike,” approved Mrs Mayhew, smiling kindly at her.

“Look, if you females want her to improve, hold your gab,” he said heavily. “Have you thought about it, at all, Miss Martingale?”

“Thought, sir?”

“About the play! About Viola! About what’s going on, here!”

“I—I have always thought that she is a very courageous person, very independent, who—who is worth ten of Orsino,” she ventured.

“That’s true enough!” said Mrs Deane with her throaty laugh. “Only I’d make it fifty! Lor’: he sits there a-mooning over this worthless dame—begging your pardon, dear,” she said to her sister, who was due to take the part of Olivia, “instead of getting out and doing something about it, like a man!”

“Yes, well, never mind that,” said their producer briskly. “What I mean is, Miss Martingale, have you envisaged this here scene? What is she a-doing?”

She looked dubiously at the worn copy of Shakespeare that had belonged to her father. And which was, besides her chintz dress and chip hat, the only thing she had salvaged from her cousins’ house. “Um—well, they have just arrived… Oh.”

“Quite. This,” said Mr Hartington, waving his muscly arm at the echoing spaces of the barn, “is a rocky shore. They’ve just been shipwrecked, barely got ashore with their lives. Would she be saying ‘What country, friends, is this?’ as if she was meeting them on, not to put too fine a point on it, The Strand? –Well,” he said before the blushing Miss Martingale could reply, “if you was a great actress and could put across the point that she were putting a brave face on adversity, she would—yes. I once saw Mrs Siddons do it, in her younger days,” he said with a deep sigh. “With merely a lift of the chin—you know? Wonderful. –No, well, us mere mortals have to forgo that sort of notion. Play it like a bewildered girl that is doing her best but is no heroine,” he said, fixing her with a stern eye, “and that might be a bit out of breath, and very shaken up about her brother. And just remember, however odd the plot might strike as, people do very odd things when they think they’ve lost their nearest and dearest; dare say she might run off and put on breeches and serve Orsino—why not? Right: go on.”

Miss Martingale hesitated. Then she said: “May I stand?”

“Whatever you please. Sam can help you,” said Mr Hartington without any appearance of interest.

Mr Speede got up and allowed Miss Martingale to tug him into position, and to explain to him that it would greatly help if they were to come in from over there, panting.

They came in from over there, panting; and she grasped the sturdy Mr Speede’s arm and pulled him to a halt, gasping: “What country, friends, is this?” –Mr Hartington’s eyes might have been seen to narrow fractionally, but he said nothing.

The Captain wiped his brow, removed his non-existent cap, and allowed: “This is Illyria, lady.”

She shook his arm fiercely and cried sharply: “And what should I do in Illyria? My brother, he is in Elysium!” Then she bit her lip, released him, turned away, swallowed with difficulty, and said hoarsely: “Perchance he is not drowned: what think you, sailors?” Looking up at Mr Speede with painful hope on her face.

Mrs Hetty at this point nodded very hard and brought her hands together silently; and the sisters looked at each other and nodded. Mr Hartington did not speak, but his attention did not waver.

The scene continued, with Viola pulling herself together and managing to speak much more like the independent, courageous person whom Miss Martingale had earlier described. Mr Speede, as the Captain, shaking his head dubiously over her plan, but going along with it.

As they turned to exit Mrs Hetty clapped her hands vigorously and the two sisters, smiling, followed suit.

“That’s a bit more like it,” said Mr Hartington on a tolerant note.

“Thank you, sir. –Mr Speede, you were wonderful!” said Miss Martingale with shining eyes. “I never could see, before, why on earth he did not speak up and stop her—though of course the plot demands the device—but you made it so plain he is very doubtful about the whole thing but lets her go on with it largely out of sympathy and partly because of their relevant positions in life!”

“Yes, you can keep that touch of the forelock in, Sam,” said Mr Hartington generously. “Now do you see what I mean about thinking about the scene, Miss Martingale?”

“Yes. I was very bad before,” said Miss Martingale humbly.

“Aye, well, acting is not like speaking poetry,” he said firmly.

She nodded hard. “Not in the least!”

“So, can she have a small part?” demanded Mrs Hetty.

“Not in this, it’s cast. Well, you can understudy Angelica and Louisa, in t’other, for if that Georgy comes down with a damned bellyache someone will have to go on for him, and I don’t see Hetty in the part,” he said genially. “And it won’t hurt if you get up in Viola, but don’t imagine as I’ll let any untried amateur go on for Tilda. If she breaks her leg we don’t do the piece: get it?”

“Yes, Mr Hartington,” said Miss Martingale meekly.

The actor-manager scratched his chin slowly and admitted: “We-ell… I was thinking of getting up a light comedy. Pity we ain’t got time, really, to learn up the parts and do it here. Well, see how it goes, hey? Sam will find the parts.—Three Belles And A Beau, Sam.—It’s more a farce, in actual fact, Miss Martingale: nothing to it, but the groundlings like it,” he explained. “We’ve transposed it from the village green of its original settings to a drawing-room, and it seems to go over a treat. You can be Miss Fancy, Tilda usually takes Miss Pretty, and Nancy can do Miss Gaye. Sid can damn’ well take the Beau, and like it. No, well, them others haven’t got no stage presence,” he said as Mr Speede began to object that David or Paul might do it. “But if he don’t get here, Paul can have it.”

That seemed to be that; he turned his attention to other matters.

Miss Martingale wanted very much to ask someone if he really had approved of her Viola, but there did not seem to be the opportunity until very much later that evening. At which point Mrs Hetty, yawning very much, confirmed that of course he had, he would never have offered her so much as an understudy if he hadn't, and Miss Fancy was a very good part. And Miss Cressida must play her vain as vain, but also full of whims and fancies: niffy-naffy, see?

Miss Martingale nodded obediently, and went off to the tiny room she shared with Tilda and Georgy, and the tiny truckle bed she and Troilus shared therein, fully intending to read her part until the candle guttered. But even though Georgy was snoring loudly, as was his wont, and even though Troilus lay very heavily upon her feet, also snoring loudly, for he had had a wonderful day hunting for rabbits, and quite possibly badgers, in the meadows round the barn, she found that her eyelids kept drooping. So she blew the candle out and was immediately off in the land of dreams. Where she became Mrs Siddons, triumphing extremely as Viola; the only maddening thing about it being, as she realised crossly, waking some time before dawn, that the face of the gentleman who played Orsino remained mistily veiled. His legs in white silk stockings were unmistakable, but— Had it been the mellifluous voice of Roland Lefayne, or another, much meeker voice? She made a face, turned over cautiously in the narrow little bed, and fell asleep again.

“Ay shell hev,” said Mr Grantleigh importantly. “sleshes hyare, hyare, end hyare.”

“Ye-es…” Miss Martingale peered at the sleeves of his Elizabethan “jarkin”. “Sir, I do not think there is enough stuff to allow me to finish the slashes neatly.”

“It cennot signifay. Effect is all, in the thyahtre.”

“Ye-es… Um, well, the thing is, what if they wish to use the jerkin another time?”

“Qui’,” noted Mrs Hetty through a mouthful of pins.

Mr Grantleigh shrugged his splendid shoulders. “End pray make shah thet the shartsleeves puff through the sleshes.”

“Yes, Mrs Wittering has shown me how to achieve that, sir; it is all a trick!” said Miss Martingale eagerly.

Mr Grantleigh yawned. “Rallih? Splendid. –The crimson hose, if you please.”

“Yes, I shall remember: it is all writ down.”

Nodding condescendingly, the splendid Mr Grantleigh resumed his own outer clothing and wandered out of the parlour: the which the wardrobe mistresses had turned into a sewing and ironing room, for the nonce.

“Next, please,” said Miss Martingale firmly, opening the door to the narrow passage, where a gaggle of merry young men was propping up the wall, laughing, tossing coins, and, she rather thought, competing as to who could tell the greatest lies.

Mr Pouteney came in, smiling. “Feste, the clown,” he reminded her.

“Ye-es… I have you down here as a courtier, sir,” she said dubiously, consulting her list.

“Yes, I shall walk on at Orsino’s court in the first scene,” he agreed. “Harold wants as many of us as possible on scene, to make an effect. Want me to try that costume?”

“Yes, please.” Miss Martingale looked at his bright blue eyes and shiny black curls and said apologetically: “I am afraid it is a horrid yellow shade, sir.”

“That matters nothing at all, to a professional!” replied Mr Pouteney cheerfully. “Do your worst, Miss Martingale!”

By this time she had almost got used to the sight of young men in their undergarments. So she said firmly: “Then if you would try the yellow doublet and hose on, sir. And these puffy breeches go with them, but of course we shall take them in for you.”

Obligingly Mr Pouteney scrambled out of his clothes and got into the yellow outfit, remarking as he did so: “Who the Devil wore these breeches? Falstaff?”

“Merry Wives,” confirmed Mrs Hetty.

“Lor’, should one be flattered?” he murmured. “Take them in two feet or so, Miss Martingale!”

She grasped enormous volumes of breeches at his slender waist, and nodded feebly.

“Could I have a pretty ruff, as a compensation?” he murmured, twinkling.

“Cut up that apron,” prompted Mrs Hetty, holding up a jacket and frowning at it.

“Um—yes. Well, we propose to starch it, Mr Pouteney. And Mrs Wittering has a splendid trick of sewing it to some stiff paper as well. It does not show, when you are on stage, sir.” She showed him the apron doubtfully, pointing out that the edging was not lace, just cut work, but to her great relief, Mr Pouteney beamed and approved. And went amiably to let Mrs Wittering try on him a set of red and green fleshings which were largely what he would wear as Feste. Together with a jester’s cap which Master Georgy, under Mrs Hetty’s eagle eye, was at this moment restuffing, for it had become very limp.

“What a pleasant young man he is,” noted Miss Martingale as he thanked Mrs Wittering very nicely and went out.

“Yes, Paul’s a nice boy,” agreed Mrs Hetty. “Don’t you judge ’em all by that dratted Reggie, me dear!”

“No,” she murmured, smiling a little.

“Any more?” said Mrs Hetty, inspecting Georgy’s stuffing with an eagle eye. “That’s a good boy. And if you promise to do ’em nice and tight, you can sew the bells on. –Any more?”

Major Martin’s daughter pretended to consult her list. “Mr Amyes.”

“Get him in. And don’t take any nonsense from him, me dear. Walk-ons do not dictate the number of slashes they has.” Mrs Hetty picked up the jacket destined for Mr Grantleigh. “Rubbish,” she pronounced grimly. “He can have one slash, and like it.”

“Yes,” she said limply as her brother came in, looking meek. “Very well. Um, Mr Amyes, I have you down as a courtier at Orsino’s court.”

“Yes. Mr Hartington has ordained that I should hold a pomander. And sniff at it, y’know?”

“That’s props,” said Mrs Hetty tersely. “Speak to Sam.”

“Oh, but he said I should speak to you, Mrs Pontifex,” he said, opening his eyes very wide.

“That means,” said Mrs Hetty grimly to Miss Martingale, “that he thinks we’re a-going to make one.”

“It can h’easily be done, with a ball of rags, and some thread or cord, and a touch of gold paint, if there be such h’available,” ventured Mrs Wittering.

“Gold paint, for the likes of him? I should think not! Use a bit of yellow cord.”

“One is reliably informed, ma’am,” said Ricky with a sparkle in his eye, “that yellow cord will not shine under the lights.”

“You get gold paint when Harold tells us in person, and not before. Get them clothes off, we ain’t got all day,” she ordered grimly.

Laughing, he divested himself of his outer garments. “Green, they said,” he murmured.

The green satin suit was a particularly lurid shade of emerald. His sister picked it up with some satisfaction. “Quite right. I am afraid the hose are a different shade altogether, but that cannot be helped.”

Ricky looked in horror at the olive-green hose. “My God!”

“Mrs Wittering could provide some ribbon, sir: you might wear them cross-gartered,” said his sister dulcetly.

Mrs Hetty gave a shriek, and collapsed in hysterics; and Mrs Wittering, hurriedly whisking out a handkerchief, buried her sniggers in it.

Winking, Ricky acknowledged: “That’s one for me, hey? Well, do your worst.”

Mr Amyes was duly got into the full outfit: it comprised short, puffed emerald breeches over a pair of tight, short, gold brocade drawers which came halfway down his thighs, and the olive-green hose under those. The body was adorned by a pease-cod-bellied jacket with a short cloak, to be worn flung back. A la Hussar, as Mr Grantleigh would have put it. The original ruff, which had been a short, neat one, had long since vanished, and Miss Martingale produced a somewhat fuller one, which successfully concealed the appeal of her brother’s strong but slender neck.

“There’s an ’at, Miss Cressida,” Mrs Wittering reminded her.

So there was. Small-brimmed, with a conical crown, and a green fluffy thing on it that from the furthest point of the circle might have been believed to be an ostrich feather: actually a tangle of green silk unravelled from, at a guess, a scrap of the satin. Ricky ruffled up his curls, which in the person of Mr Amyes he wore slicked back over the ears, and set it jauntily aslant them, striking an attitude, one hand on the hip on the side on which the cloak was flung back. “Well?”

Mrs Hetty was heard to gulp, but rallied to say: “Has to be worn with high-heeled shoes. What the wardrobe can provide, but you will have to wear ’em, however agonising, acos there ain’t no choice. And if you’ve got the guts, an earring is reckoned to be very Elizabethan.”

“Oh, I have the guts!” he said with his charming smile.

Sniffing, she muttered: “I’ll wager. –Well, you can take it in at the back for him, Miss Cressida, deary, and if you’ve got the time, tack them sleeves up a fraction, they’re a bit long. And take them half-drawers in, they’re not supposed to be baggy in the thigh. Otherwise, he’ll do.”

“Is there an earring?” asked Mr Amyes, standing his ground.

“Eh? Oh.” Mrs Hetty fumbled in a box. “This one ain’t got a pair. Ugly thing, ain't it? Tie it on with a piece of pink silk, it won’t show.”

Smiling at her, Mr Amyes slid the earring into the hole in his lobe.

“When did you have that done?” gasped his sister in horror.

“Oh, some time back, in Paris. Necessity is the mother of invention, is it not? Thought it might have closed up, actually.”

“Don’t you ask him one thing more, deary, he’s dying to tell you!” said Mrs Hetty sharply. “Right: get on out of it, we haven’t got all day!” she said briskly to Mr Amyes. “And we’ll see you all back here this evening without fail, or you don’t get yer suppers.”

Mr Amyes bowed gracefully. “Your wish is my command, ma’am.” And proceeded to resume his own garments and take himself off.

In his absence there was a short silence.

“Earrings? I never heard the like,” said Mrs Hetty somewhat feebly.

“Sailors often ’ave ’em,” said Mrs Wittering limply.

“That’s right!” squeaked Georgy Trueblood.

Mrs Hetty got up and came to look at his stitching of Mr Pouteney’s bells, but replied to Mrs Wittering: “Yes, and Harold had his ears done when he did that thing with Captain Morgan, but a young lad like that? Prancing around Paris with his ears pierced?”

Mrs Wittering eyed Miss Martingale sideways, and coughed.

“Oh,” said Mrs Hetty somewhat lamely. “Yes. –Well, never mind him, Miss Cressida, deary, get on with your stitching.”

Obediently she sat down with her sewing.

“Can you use a hammer?” asked Mr Speede tersely.

“Not I, alas,” replied Mr Amyes cheerfully.

“In that case, grab this bit of wood and hold it firm,” replied the stage manager grimly.

Feebly he obeyed. Asking, as the hammering abated: “What are you making, Mr Speede?”

Slightly mollified by not being addressed as “Sam”, the which Mr Grantleigh had done before scarce being introduced, Mr Speede replied: “Frames for the flats, first off. See, Harold’s actually got some new canvas, and we can paint it up quick as nothing, only needs a bit of a balcony and some sky and cypresses, and that’ll be Olivia’s garden. But when we’re on tour, we make them so as they can be rolled up, otherwise some noddy’ll be bound to put his great foot or a chair leg or some such through ’em. These here wing nuts and bolts, they go on the ends, and we bolt the horizontals to ’em, see? Then for the performance we screw the flats to them good solid uprights, or certain fools what I could name’ll have them over in the middle of Harold’s big scene. Only they come off, after. Don’t do it the same, quite, for a decent theatre, only if we lay eyes on one o’ them this tour, you can call me a Dutchman. Gimme that brace and bit. –The DRILL!” he shouted as Mr Amyes looked blank.

“Oh—this? I do beg your pardon.” Mr Amyes handed it to him and watched with interest as Mr Speede drilled holes in the ends of his horizontals and fitted bolts and what were presumably wing nuts.

“Can you paint?” he then asked, propping his handiwork up and eyeing it judiciously.

“Well, gouaches. I can sketch, a little, but I’ve never done anything on that scale.”

“No, well, if you can hold a paintbrush, that’s more than what the rest of them can. But you’d better get out of them good clothes.”

Perceiving it was to be his fate to paint large stretches of canvas matte blue, Mr Amyes went resignedly to get into the oldest shirt and breeches he owned. Accepting with some gratitude Mr Speede’s offer of a large and grimy smock to go over them.

… “What ’e made,” owned Mr Speede with a grimace to his old friend and partner in the tap, some considerable time later, “the prettiest bumpkin you ever did see. If he sticks it out until we get to London, Harold, you did ought to think serious about casting him as Perdita’s princeling in The Winter’s Tale. Acos Percy Brentwood’s only got to lay eyes on him, to grab him out from under your nose!”

“Mm.” Mr Hartington sipped cider, and thought about plump widows, and refrained from mentioning to Mr Speede that he hoped very much not to have to return to London and think about casting The Winter’s Tale or anything.

“I’ll ’ear your lines, if you’ll ’ear mine, Miss Martingale,” proposed Master Trueblood firmly.

Limply she agreed. There was no-one else available: they all seemed to be terribly busy. Well, Mrs Wittering might have obliged, while she stitched, but she had discovered that the little seamstress could not read very well.

“Nah!” said Georgy scornfully as she began to recite the part of Miss Fancy. “Not like that! This is lines, see? You ain’t upon the stage, now. Now, ’old on, I’ll show yer.” Looking superior, he rapidly mumbled his way through half a page of Miss Louisa Addle. “See? Lines! Leave out the expression!”

Humbly she nodded, and began mumbling her way through Miss Fancy. Very disconcerted to find that Master Georgy read the responses as: “Hum, hum, hum”, followed by the last word of the speech.

“Um, I think I might remember better if you were to read more of the other characters’ speeches,” she said humbly as he reproved her for a rotten memory.

“Nah! These is cues, see? Cues!” he retorted with terrific scorn. “And get on with it!”

Humbly she got on with it.

Master Georgy’s memory proved not so reliable as her own, or else he had not been studying as hard as he had been told; she felt quite timid about taking him up, but as he became very cross when she did not prompt him, soon learned to do it quickly.

“Boring part, really,” he pronounced as she handed him his script back.

“Little Louisa? I thought it sounded quite jolly,” she said feebly.

“Nah! Acos there ain’t no be’eadings, nor wicked uncles, nor abductions, nor nuffink!” he retorted scornfully.

Miss Martingale nodded meekly. So much for M. Molière.

“At last,” said Mr Dinwoody under his breath as the familiar fawn and pink dress and the old chip hat appeared outside the huddled old inn. He ceased leaning against a gnarled old tree, and strolled forward slowly. “Morning, Missy!”

“Good morning, Mr Dinwoody!” she cried, holding out her hand.

Mr Dinwoody engulfed it in a gnarled one, and then bent to pat Troilus. “Morning, young shaver,” he added cheerfully to the curly-haired object accompanying the pair.

“’Oo are you?” replied Master Trueblood aggressively.

Mr Dinwoody eyed him in some amusement. “Bert Dinwoody’s the name. And who might you be, eh? –Never seen ringlets like that before on anything what ’ad been short-coated,” he noted in a loud aside.

Master Trueblood cried gamely, sticking out his rounded chin: “Georgy Trueblood, well known in the theatres of Drury Lane, and capable of taking an infant, boy or girl! And been upon the boards since my cradle! And get off Troilus, ’e’s our dog!” At the same time, however, a small, hot, sticky hand seized Miss Martingale’s tightly.

“It’s all right, Georgy: Mr Dinwoody is a friend of mine. And he know Troilus very well,” she said as the little dog capered and frisked.

“’E can’t ’ave ’im! Acos I’m learning ’im up to be a professional dog!” he cried shrilly.

“He does not want to have him,” she replied reassuringly. “But Troilus knows him very well, you see?”

Master Trueblood glared at Mr Dinwoody.

“Georgy appears in the plays, sir: he is a professional actor, even although he is young,” she explained somewhat feebly.

“Gawdelpus,” replied Mr Dinwoody simply.

“Mr Dinwoody, please do not be unkind. On his mother’s side, Georgy’s family has been in the acting profession for a very long time. He is lucky to have had the opportunity to have been offered work.”

“Aye. From Lunnon, are you, young shaver?” said Mr Dinwoody on a more tolerant note.

“Born and bred,” he replied, eyeing him warily.

“Uh-huh. Ain’t got no dog of your own, then?”

Reddening, Master Trueblood retorted: “We would if it took our fancy. But Pa’s out all day and ’alf the night, driving ’is ’ackney carriage, and Ma’s upon the boards, and me sister too, and like as not we’re on tour for months on h’end, so it ain’t convenient, see?”

“No,” agreed Miss Martingale, attempting to frown at Mr Dinwoody without Georgy’s perceiving her do it. “Of course it is not. But as we are on tour, Georgy is taking the opportunity to give Troilus some training in how a theatrical dog should behave.”

“If it was me, I’d take him rabbiting instead,” said Mr Dinwoody neutrally.

“Rabbiting?” said Master Trueblood uncertainly.

“Aye. See them teeth? They’re not for show, you know.”

Desperately Troilus’s mistress interposed, as Georgy’s grasp on her hand tightened and he looked very warily indeed at the little dog: “Dear Mr Dinwoody, I know you mean well, but Georgy is a town boy, he would not know how to catch a rabbit.”

“Troilus would, though. –Hey, boy?” said Mr Dinwoody.

At this Miss Martingale’s traitorous dog gave an excited bark, and ran round Mr Dinwoody’s ankles.

“Come on down this way,” Mr Dinwoody then said, taking her arm.

Limply she let him lead them down an obscure lane, very much overhung with wildly overgrown hedges and old trees.

“Ah,” said Mr Dinwoody with satisfaction as they came up to an old wooden gate. He leaned his elbows upon it and gazed into the field. “Rabbits. –See over there, where the ground’s a bit broken? Just keep quiet, and keep Troilus quiet, and wait,” he ordered.

Obediently his mistress clipped Troilus’s lead on him, and she and Georgy waited quietly.

“There,” breathed Mr Dinwoody as suddenly several ears flicked into view.

“Lumme,” whispered Georgy, his eyes bolting from his head. “They’re alive!”

The prudent Mr Dinwoody with one smooth movement had scooped Troilus up and clapped a hand over his muzzle. “If I let ’im go, you promise not to bawl if ’e gets one?” he whispered.

Eyes shining, Georgy nodded. “Promise!” he hissed.

Mr Dinwoody unclipped Troilus’s lead, knelt down and held him to the gate. Prudently taking his hand off the muzzle at the very last moment before releasing him. Troilus was through the gate and streaking for the luckless rabbits before anyone could utter.

“He’s GOT one!” shouted Georgy at the top of his lungs.

“Good boy, Troilus! Cummere!” Mr Dinwoody gave the whistle through the front teeth and Troilus galloped back lugging the limp prey: half his own size.

“There,” said Mr Dinwoody. “That’s what dogs are for, sonny. Troilus could keep you in hot dinners without ’ardly stretching himself. Eh, boy?”

Limply his mistress patted the killer. “Yes. I didn’t think he could,” she said feebly. “I had him from a lady who lived in a city.”

“Bred to it, they are, Missy. Badger-hound, ain’t ’e? Yes, thought so. –No, we don't want ’im to find a badger, no eating on a badger,” he explained to Georgy.

“Right. No eatink on a badger,” he agreed, faint but pursuing. “’Ere, we could eat this rabbit! It’s just like the ones Ma gets down the market!”

“Some on ’em, yes. This is a wild rabbit, though. More of a gamey taste to them, need slow simmering,” said the expert Mr Dinwoody. “Yes, well, we’ll take it back and give it to the landlady to cook for you, hey?”

“Yes!” he breathed, eyes shining. “’Ere, ’ow’ll we make sure it’s our rabbit, though?” he asked in sudden concern.

“Dunno. Well, some cooks you can trust and some you can’t.” Mr Dinwoody pulled his cauliflower ear. “Maybe if you was to go in the kitchen and watch ’er prepare it?”

“Then I’ll see the dish what she cooks it in,” he agreed, his speedwell-blue eyes narrowing. “Right you are, sir! –Maybe there’s more,” he added, looking longingly at the hillocks where the rabbits had long since vanished.

“Maybe there are,” agreed Mr Dinwoody stolidly. “You take Troilus and go and see, eh? And if he gets stuck down a burrow, for God’s sakes give us a yell.”

“Right!” Brushing off Miss Martingale’s offer of help as if it were a fly, Master Georgy clambered over the gate, called to Troilus, and raced across the field.

“Poor little bleeder,” concluded Mr Dinwoody, leaning on the gate.

“He is a town boy,” she said limply. “More used to helping stitch the costumes than to playing in the fields, let alone hunting. Um, as a matter of fact I do not think he realised he might play in the fields,” she admitted, swallowing. “We’ve come this way before and he never so much as suggested it. Thank you so much, Mr Dinwoody!”

Mr Dinwoody winked at her. “No, well, it were about six to four he’d bawl when the dog got the rabbit, but I thought I’d take the chance. So, how’s it all going, Missy?”

Eagerly she poured out tales of costume-making, reading for Mr Hartington, etcetera.

“Good. That all?”

“Oh, yes!” she agreed with an artless smile.

“That’s good. –I was wondering if there might be any odd jobs, Missy, for a man as is handy with a hammer and nails?”

“Mr Dinwoody, Mr Speede will fall upon your neck and kiss you!” she owned with a laugh. “For although he has found a competent local carpenter, the man cannot do a thing without direction! And all the young actors are hopeless! Mr Ardent did offer but he knocked the nails in all crooked. Mr Pouteney broke a fingernail the other day and almost wept over it, and Mr Grantleigh will not do anything that might risk disarranging his hair or neckcloth. And Mr Darlinghurst, who is such a pleasant, quiet young man, became positively virulent and said that last winter he had a pot of paint knocked off a ladder onto his hair and had to shave it all off, for it would not come out, and nothing would persuade him to go near the scenery again!”

“Right. Well, I got an errand over to Axminster today, but I can be here bright and early tomorrow, if Mr Speede’ll have me.”

Miss Martingale assured him that he would, and, collecting up Georgy and Troilus with some difficulty, they returned to the inn. There Georgy saw his rabbit safely into the kitchen, and skinned, cleaned and chopped up for a stew. Which the kindly Mrs Potter assured him would be brought to the table for his supper that very night.

“’Ere! See?” shouted Georgy, his round cheeks very red, as the steaming rabbit stew was brought in by the beaming Mrs Potter.

“That must prove it,” acknowledged Mr Hartington gravely. “Well done, Troilus!”

“You can ’ave a taste, sir, if you like,” said Georgy generously. “Only not them others,” he added, looking under his lashes at where the younger actors, clustered round an inadequate small table with Mr Speede, were drinking copious amounts of the local cider and encouraging Mr Amyes to recount episodes of his Continental career, to the accompaniment of shouts of laughter and thumpings of the said table. Mr Speede, alas, joining in with as much relish as any of the youngsters.

“Certainly not,” agreed Mr Hartington solemnly.

“Well, fancy that!” gasped Tilda Trueblood. “Our Georgy catching a rabbit!”

“It was Troilus, really,” admitted Georgy. “It was good, though: he was at its neck in a flash: grrr!” he illustrated, baring the small, white, shiny even teeth which were, according to this mother, one of his greatest assets.

“Yes,” said Tilda faintly.

“He ought to have some,” said Georgy, looking at Miss Martingale.

“Only if you say so,” she said with a smile.

Georgy decided that he definitely did say so, and so a bowl was brought for Troilus, and the rabbit shared carefully amongst the killer himself, Master Georgy, Miss Trueblood, and Miss Martingale, with tastes for Mr Hartington, Mrs Hetty and Mrs Wittering. And of course pronounced the very best rabbit stew that had ever been.

“Thank you so much, Miss Martingale,” whispered the little ingénue as the two retried to bed later that night to discover Georgy already fast asleep at the foot end of Tilda’s bed, with Troilus cuddled under his chin.

“I hope it was truly all right?” she asked anxiously.

“Yes; he don’t get much chance to be a real boy,” said his sister sadly.

“I know,” she agreed, swallowing. “I—I wish you would call me Cressida, if you would.”

Miss Trueblood nodded eagerly, and said she was Tilda, and perhaps they could be friends? Adding shyly that she could see that Cressida was not like all the others.

“No,” said that maiden dubiously. “Well, I hope in time I shall learn to act as well as all of you.”

“Not that,” said Tilda, blushing fierily. “Well, the ladies with this troupe of course are all older, so you don’t see it so much. In general, the ingénues talk about nothink but beaux and gentlemen,” she disclosed, redder than ever.

“I see! Well, that is not confined to their walk of life, I can assure you!” Major Martin’s daughter got into bed and, sitting up and hugging her knees, began to tell Tilda, with considerable relish, about her cousins Belle and Josephine Dearborn. Considerately in a lowered voice so as not to disturb the snorers.

Tilda laughed very much—though also in a lowered voice, managing it quite easily, being a child of the theatre; and confessed she had not known that young ladies were just as silly.

“I would say, sillier, but I think you would dispute that?”

Tilda nodded very hard, giggling, and the two damsels fell innocently asleep in their narrow little beds. The sweet-natured Tilda considerably cramped up, because she had not the brutality either to push her snoring little brother aside, or to remove Troilus Martin bodily from their bed.

“It’s a carriage,” reported Mrs Mayhew from the parlour window, next day. Most of the actresses had been fitted for their costumes during the previous day while the men were out delivering handbills, but Mrs Mayhew’s dress as Mrs Addle was being made from scratch, so Mrs Wittering had merely cut out a pattern the previous day and was now fitting the result on her.

“It’ll be a treat for the carriage trade of Exley St Paul to see you in your petticoat, Margery,” noted Mrs Pontifex drily.

“It probably will, at that,” replied Mrs Margery, unmoved and unmoving. She peered. “Can’t see a thing through these little panes—have you noticed the glass is quite distempered?”

“Distorted, dear; yes,” agreed Mrs Hetty placidly. “You wouldn’t expect no better from these obscure country places. Carriage and four, is it?”

“Yes.”

“Purple liveries?” asked Mrs Hetty very drily indeed.

Mrs Mayhew peered. “Um—don’t think so.”

“Probably ain’t Sid, then.”

Master Georgy had again been seconded to help stitch and stuff, as the rest of the players were rehearsing Twelfth Night: he rushed to the window. “It is!”

“It’s a gent in a hat: could be anyone,” admitted Mrs Mayhew.

“It is him! Mr Sid!” he screeched, rushing out.

“Wait and see,” advised Mrs Hetty.

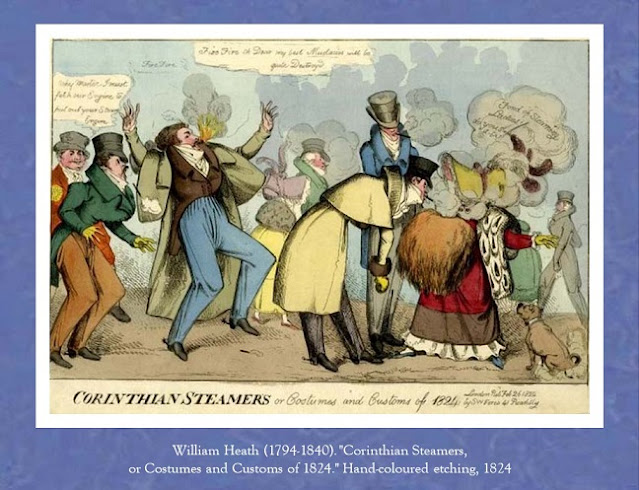

They did not have to wait very long before they saw: there was the sound of Georgy screeching excitedly in the inn passage, and then the door was swept open, and there he was, in all his glory. All in shades of fawn: from the immaculate breeches to the many-caped greatcoat which would not have disgraced a Corinthian in a curricle. Sweeping the hat off and bowing very low and saying with a laugh: “Enter Orsino, with a mouthful of apologies!”

“You would do best to save them for Harold,” recommended Mrs Mayhew.

Mr Lefayne grinned, and came in. “’Morning, ladies: lovely morning, is it not?”

“It’s dinnertime, by my reckoning,” replied Mrs Hetty stolidly.

“Oh, pooh, don’t be such a grouch, Hetty, dear!” Gracefully he kissed her cheek. Gracefully he came to salute Mrs Mayhew. She returned the embrace with a hearty kiss on the lips, but removed the hand that was carelessly investigating her petticoat. Unabashed, Mr Lefayne went to drop a kiss on little Mrs Wittering’s faded cheek.

“Delighted to see you have joined us, Miss Martin,” he then said, bowing low.

“Miss Martingale, Sid: thought it best, acos she’s got away from them blamed cousins,” explained Mrs Pontifex illuminatingly.

“Miss Martingale, then,” he said with another bow.

“Good-day, Mr Lefayne,” replied the renamed Miss Martingale with a blush, rising and dropping a curtsey. She had somehow forgotten, in the intervening months, how very—very overwhelming Mr Lefayne’s personality was. And how charming he could be, she reflected lamely, as he then made a great fuss of Troilus, rising at last with the little dog in his arms.

“Harold very cross, is he?” he said lightly.

“Hollering his head orf over nothink,” replied Mrs Hetty with relish. “Which you may say is not unusual in your actor-manager, and anyone what has ever endured Percy Brentwood would not think nothink of it. Only they all say he’s ten times worse than usual, and what did you have to go and do it for, Sid?”

“I am not so very late, am I?” he said with a laugh. “And I am up in my lines!”

“Yes? Well, in that case Georgy will no doubt be thrilled to show you to the barn in what they are rehearsing,” said Mrs Hetty coldly.

“Yes! And can I ’ave it now?” asked Georgy eagerly.

“Why not? BOY!” shouted Mr Lefayne loudly.

“If you was expecting that dim-witted Tom Potter to answer—” Mrs Hetty broke off, for Tom Potter, grinning, not to say blushing as he caught sight of Mrs Mayhew, had presented himself.

“Emollient in the palm,” explained Mr Lefayne gracefully. “Bring the large carpetbag in here, if you would, Tom.”

Tom Potter speedily obliging, Mr Lefayne opened it. “Now, that’s from Aunt Cumbridge,” he said, presenting Georgy with a box tied in a ribbon, “and don’t eat it all at once. –Treacle toffee,” he explained to the company. “Let’s see… Well, she don’t know all of you, but she’s put up a fruit-cake for Harold, and some more of the toffee for Nancy and the lads… Ah! Compliments of the Miss Whites’ emporium, in Nettleford,” he said, bowing and handing out packages to Mrs Hetty, Mrs Wittering, and Mrs Mayhew.

Numbly they opened them. Mrs Mayhew’s was a selection of embroidered silk ribbons of the most expensive kind, Mrs Hetty’s a lace-edged handkerchief, which the elderly actress gasped at, and Mrs Wittering’s a lace-edged cap, which the little seamstress protested in a shaky whisper was much too good for her.

“Nonsense,” said Mr Lefayne, coming to drop a careless kiss on her forehead. “I command you to wear it—and don’t dare give it to any of the actresses, or let ’em wear it in a piece!”

Mrs Wittering tried it on immediately, and decided she would wear it under her bonnet to church on Sunday! Mr Lefayne blinked slightly but made a speedy recover and agreed that he would look forward to seeing her do so. “I had the most delightful time shopping, in the company of some charming little friends of my niece’s, and will be vastly insulted should any of my gifts be refused,” he added lightly, delving into the bag again. “This is probably far too young for you, George, old fellow, but have it anyway,” he said carelessly, hanging him a strangely-shaped parcel.

Naturally everyone’s attention remained fixed on Georgy as he unwrapped it. “A monkey,” he said dubiously as a small hairy figure in a red cap and jacket was revealed.

“Aye. Wind the key,” said Mr Lefayne.

Georgy wound the key, and the monkey proceeded to beat a brisk rat-tat on the small drum it was carrying. “It is not half bad,” he owned in a tolerant tone.

The actor looked at the sparkling eyes, and smiled a little. “Aye, well, it will while away an idle moment, I dare say. –Now, Miss Martingale, you must absolutely not refuse this,” he said with a bow, “or my feelings will be eternally crushed.”

Blushing, she accepted it, thanking him shyly. A pretty little fan of embroidered organdie. Mrs Mayhew came to admire it. “Lud! These sticks are never ivory?”

“No, I’m afraid not. Bone, I think. Quite pretty, however,” said Mr Lefayne carelessly. “I hesitated, Miss Martingale, but thought you might prefer a trifle such as this to a mechanical toy: there was a pretty little lady playing a spinet, and as I know Tilda is very fond of music, I thought she might care for that.”

“I am sure she will, sir! And I have never had a fan before! Thank you so much!”

“In actual fact, she has not anything, for she came away from the demned cousins’ house, if you will pardon my mode of expression,” said Mrs Mayhew on a grim note, “with only the clothes that she stood up in.”

“You must tell me the whole later,” he said lightly. “For the nonce, I suppose I had best fly to Harold’s side!” He grimaced, laughed, bowed, and was gone.

Mrs Hetty sighed. “He ain’t all bad,” she conceded heavily.

Georgy had his mouth full of toffee and was winding his monkey again; Miss Martingale, very pink-cheeked, was fanning herself with her fan; Mrs Mayhew was trying a knot of ribbon in her hair before the mirror on the mantel—not the property of The Dancing Dog, but Mrs Wittering’s own; and Mrs Wittering was folding the lacy cap carefully and laying it in its silver paper again. So no-one contradicted her.

Mrs Hetty sighed again. “No,” she said dully.

“Delighted,” said Mr Dickon Amyes, bowing very low to Mr Lefayne.

Sid eyed him drily. “Likewise. Here to learn the business, are you?”

Mr Amyes owning that he was, Mr Lefayne then asked him drily what he had learned so far.

“Largely, to keep a hat upon one’s head when assisting to paint the scenery, sir,” said Mr Amyes politely.

Sid laughed his good-natured laugh, clapped him on the shoulder, and conceded he’d do. And advised him, if Harold hadn’t let him read so far, to insist, and see if he’d give him an understudy. And strolled off, smiling kindly.

Ricky Martin smiled and bowed; but from under his long, curled lashes he gave him a look in which considerable resentment was mingled with not a little jealousy. For if Lefayne was clearly not a gentleman, he also, clearly, had all the self-confidence of a man of the world—nay, of a man who was very sure of his place in the world, and very sure of his own worth.

… “See?” said Mr Ardent in his ear, some time later, as Mr Lefayne concluded, with a flourish: “Orsino’s mistress, and his fancy’s queen!”

“Well, yes, he makes it seem almost credible.”

“Almost?” cried Mr Ardent indignantly over Mr Hartington’s shouting at the unfortunate Mr Grantleigh, who had claimed to be expert upon the mandolin. “There ain’t another actor in London that could make Orsino seem a true man, and not a simpering fool in love with his own page!”

“I’m sure you’re right,” said Mr Amyes peaceably, handing over a sixpence. “I admit he comes over as all that is manly.”

“Aye.” The young man’s eyes shone. “Wait until he does Aguecheek!”

“Ye-es… I had a hazy recollection that Aguecheek comes in, fairly early in that last scene with the Duke?”

“Yes, he did, only Harold wrote it out,” said Mr Ardent cheerfully.

“I see,” he said somewhat limply.

“Look, he’s mad with Reggie: if you want Valentine, now’s your time,” prompted Mr Ardent.

Mr Amyes eyed him drily: Mr Ardent would not have been half so bold, nay, not one quarter, on his own account. “What do you bet I don't get it, Tony?”

“Nothing,” admitted Mr Ardent with a grin.

“Very wise!” Winking, Mr Amyes jumped down off the waggon on which the two were perched, and went to ask Mr Hartington, very meekly, if he might read now.

… “You’ll do,” concluded Mr Hartington at the end of the reading. “At least your diction is comprehensible.”

“Ay say, sah, you promised it me!” stuttered Mr Grantleigh.

“No such thing. I said if there was no-one else to take it, you might have it if we could make out a word you were saying. We couldn’t, so you don’t get it. I’m not saying that Amyes will be any good, and there is nothing to Valentine in any case, but it’ll save rewriting Curio to combine the two. –Study it up and be ready to rehearse it without the book tomorrow,” he ordered.

Not revealing that he had prudently studied it up already, Mr Amyes bowed, said: “Your wish is my command, sir!” and retired to the waggon, grinning.

“Can’t play the mandolin, can you?” asked Mr Ardent hopefully.

“No, that one is all Reggie’s,” he returned superbly.

Mr Ardent collapsed in delighted sniggers.

Ricky Martin merely smiled; and did not reveal that he was perfectly well aware that Tony and Reggie had had a falling-out over the best of the bit-parts’ ruffs, the which Mr Grantleigh was purported to have stolen from under Mr Ardent’s nose, and that he himself was seizing upon the occasion to play one off against the other; nor that if the boot had been on the other foot and it had been Mr Ardent’s part that he coveted, the innocent Tony would not have stood a chance.

It having been impressed upon Mr Lefayne by several persons that Miss Martin was to be “Miss Martingale”, he was soon using the name as easily as if he had never known her by the other. It was impossible to tell from his manner whether he had indeed been the guardian spirit who had set Mr Dinwoody to care for her. After a day and a half of frustration, pondering the matter, she dragged Mrs Hetty out for an evening stroll and imparted the theory to her.

“Lumme,” said that worthy limply.

“There could be no-one else,” she ended, blushing.

Mrs Pontifex eyed the blush askance. “I wouldn’t say he’s shown you any special mark of favour, since he come back.”

“No, but then a gentleman would not!”

“I never heard tell as Sid Bottomley, for all ’is good points, was one of them,” she noted drily. “No, well, you may be right, deary, though I dunno as I follow it all. But ’e’s got the gelt, that’s true enough, and ’e were never a mean man. That blamed monkey of Georgy’s will of set ’im back a fair bit, y’know: Madam once fancied something like it and ’er gent of the time—not Sir George Drew, dear, afore him—’e told her to whistle for it.”

“Well, um, should I mention it to him, do you think?” she murmured.

“Up to you. Dunno as I would. Might give him an opportunity what ’e couldn’t pass up,” she said with a hard look. “No, well, they is most of them like that, and say what you will, deary, it do seem to be the male nature.”

“But surely it is the mark of a gentleman—I should say, of what that silly Angélique would call an honnête homme,” said Miss Martingale with a little smile, “that he does not permit his baser animal nature to control his behaviour.”

“I dare say. Not that I know what you mean by an oniton, dear. Nor I don’t think as I knows any Angélique, neither.”

Pinkening, Miss Martingale revealed that she meant the female lead in Mr Hartington’s play. And that Mr Hartington had very kindly lent her his copy of Molière, on hearing that her father’s books had had to be sold. “Mr Hos advised it would be for the best. We didn’t get very much for them, however,” she said with a sigh.

“Well, they’d be blamed heavy to lug around with you, dear. And then, you'd of had to leave them with Cousin D., in any case: what a waste! But if you mean the Froggy book what Harold got the play out of, don’t think it is his. It’s Sid’s.”

“Yes, so I discovered: it has his name in it,” she said, very flushed.

“Look, don’t go for to think, just because he might have taken the trouble to see you don’t come to no ’arm—which mind you, there ain’t no proof of—and because he can read French and so forth, that you got anything real in common with him, dear,” said Mrs Hetty heavily; reflecting even as she spoke that she might as well save her breath to cool her porridge. For when did a critter of that age ever imagine it had to have anything in common with the gent it had fixed its fancy on?

Blushing, Miss Martingale protested that of course she did not imagine any such thing! And, calling to her little dog, changed the subject.

Mrs Hetty sighed and shook her head a little. Girls would be girls, that was for sure. Especially with Sid Bottomley around.

“What’s that, for Gawd’s sake?” she croaked, coming into the parlour at breakfast-time the following day to find Sid in sole occupancy of it, leaning in the casement window with a foul smelling something-or-another smoking in his mouth.

“An open window. I hope the shock is not too much for you?”

“Probably more than enough for it: Margery and me couldn’t get it open nohow. No: that.”

“This is a cigar,” he murmured.

Mr Hartington entered, yawning. “So it is. Don’t tell us you met up with that Sir N. on your travels!”

“Not quite. I did meet up with his friend, Mr Rowbotham, however. Sir N. has graciously disclosed the name of his shipper to him, and he graciously gave me a box of ’em. Fancy one, Harold?”

“Not before breakfast, thanks,” said Mr Hartington, yawning again.

“Mr Rowbotham?” said Mrs Hetty dubiously. “Oh! Gent what hangs around the stage doors. Brother’s a nob: that the one?”

“Sir Cedric: our former ambassador to Prussia; mm,” murmured Mr Lefayne. “Mr R. was at my niece’s wedding, together with half the nobs of London, and drove down with me. He’s gone off to visit some friends, but has reliably promised to be back in time to see our Twelfth Night.”

“Fancy that. Dare we ask,” said Mrs Hetty, ringing the bell vigorously, “what the pair of you found upon the road to delay you?”

“Yes, go on, Sid,” prompted Mr Hartington mildly, drawing up a chair to one of the inadequate small tables.

“We did not find anything, as such. We were escorting,” said Mr Lefayne primly, “a party of ladies.” He leaned his back against the windowsill, and looked at them mockingly, his eyes half-closed, and blew out a stream of smoke.

“Ho, yes!” snorted Mrs Hetty.

“No, truly! One of Mr Rowbotham’s married sisters, a Mrs G., her close childhood friend, a Lady H., and their little daughters.”

“Go on: what were they like?” asked Mr Hartington, as Tom Potter staggered in under a laden tray.

Sid threw his cigar stub into a small bush on The Dancing Dog’s forecourt and came to sit down. “Very frilly. The two widows not elderly, the daughters very pretty; what more could one want, to fritter away a pleasant journey across southern England?”

“Widows sound all right,” admitted Mr Hartington heavily. “Pity they was ladies, though.”

Sid eyed him tolerantly. “Mm. Something like that.”

“And where was they heading for?” asked Mrs Hetty, helping herself to sausages and eyeing some fried eggs dubiously. “Or was their journey merely for the pleasure of yer company?”

“No, no!” he said, laughing. “There is black pudding, here, too, Hetty: care for some?” She rejected the offer, shuddering, and he helped himself and Mr Hartington. “No,” he said to Mrs Pontifex, “the ladies were heading for the great house here.”

“Which of course means that they will’ve invited you to sleep there in a Christian bed, instead of in the barn with them lads!” she retorted smartly.

“Not at all,” he said placidly. “It never crossed their minds to enquire if I had decent accommodation, or to offer me such. And tell me you expected otherwise and I’ll eat this damned platter as well as the black pudding upon it!”

“No, I didn’t, actual. Gentry is all the same.” Mrs Hetty sighed and poured herself a generous tankard of porter.

“Mm.” Sid eyed the porter. “There wouldn’t be any coffee, I suppose?”

“No, there wouldn’t.”

“I meant to bring some,” said Mr Hartington lamely. “Forgot, what with everything else on me mind.”

“I’ll send to Axminster for some. Meantime, please pass me the porter, Hetty,” said Mr Lefayne tranquilly. He filled a tankard, and sipped. “Not bad. Well,” he said with a smile, raising it, “as there’s no-one but ourselves here, I’ll give you a toast.”

“Yes, go on, Sid,” said his manager, smiling. “To the play!”

“That, too. No, my toast is,” he said solemnly: “perdition to the gentry.” He drank deep.

Cheerfully his fellow Thespians agreed: “Perdition to the gentry!”

“No,” said Mr Hartington indifferently. “No dogs in Molière.”

“Sir, I’ve really trained him up: he’s a thoroughly professional dog, now!” offered the optimistic Georgy.

“No.”

Scowling, Georgy said loudly to Troilus: “SIT!”

Troilus ignored him.

“That possibly proves my point, and get him off my stage,” said Mr Hartington loudly.

“I wish I ain’t never give you no RABBIT!” shouted Georgy furiously, picking up Troilus bodily and staggering with him over to his mistress’ side. “Mauvais chien!” he panted, lowering him to the floor.

“Possibly he will let him walk on as a court dog in Twelfth Night, Georgy.”

“Huh! He won’t, acos ’e’s got a heart of flint!”

Forthwith Mr Hartington proved he had, by shouting: “Get back on stage this instant, Georgy Trueblood, or lose the damned PART!”

Scowling, Georgy returned to the stage-floor area of the barn. “What do you want, Papa?” he carolled, skipping a little. “Step-mamma said you wished to see me.”

“Yes, yes; come here, come along,” said Mr Hartington querulously in the persona of Mr Addle. “Don’t skip like that, child: turn round, look up, look me in the face. Now!”

“What, Papa?” carolled Georgy, skipping a little.

“Good, ain’t he?” said Mrs Hetty in Miss Martingale’s ear.

She nodded. There was no doubt that Master Georgy Trueblood as Miss Louisa Addle was very good indeed.

Next chapter:

No comments:

Post a Comment