6

Lord Sare At Home

The man who was known at the Horse Guards as “Mr Frew” and who held the rank of full colonel had led what might fairly have been described as a double life for quite some years. Or even a triple life, given that, while the likes of Sub-Lieutenant Grant knew him as the pen-pusher from the obscure back room, and a select band of senior Army officers knew him as Colonel Luton, whose rôle was to co-ordinate the gathering of Army intelligence on behalf of His Britannic Majesty’s government, most of London Society knew him as Edward Luton, a man-about-town whose chief claim to notice was that he was old Neddy Sare’s heir.

Those members of London Society who frequented “Gentleman” Jackson’s boxing salon also knew him as useful man with his fists, whilst those who patronised the exclusive fencing salon of one, Signor Fioravanti, knew him as a decent fencer—though scarcely England’s greatest swordsman. In the whole of England only one man, an obscure Mr Masters, who had once held the rank of Regimental Sergeant-Major, was aware that Edward Luton’s preferred method of fighting was with a sword in one hand and a dagger in the other, and that thus armed, he was an exceeding dangerous man. There had been, at about the time of Bonaparte’s escape from Elba, a Mr Kent, possibly not his real name, and a M. Mercure, almost definitely not his real name, who had also had this knowledge. Neither was alive to tell the tale. The fashionable ladies who invited Edward Luton to make up their dinner tables or thrust their daughters, sisters or nieces or even their fair selves at him on account of his expectations would have laughed off any suggestion that he could ever have been involved in any such skulduggery. Edward Luton? My dear, the most harmless creature! Well—quite amusing, you know. But nothing like the charm of darling old Neddy Sare!

Edward Luton had never in fact desired to have the charm of his Uncle Neddy. He had been aware, almost from his cradle, that behind his Uncle Neddy’s laughing blue eyes and easy smile lay nothing very much at all. And certainly very little that could have been described as a sense of duty—familial or otherwise. Neddy had had a brief and inglorious career in the Army. When his older brother died and it became clear that he would inherit the title, he had very thankfully resigned the commission that the family had purchased in the mistaken belief that it would get him out of harm’s way, and taken up the rôle of man-about-town, Pink of the Ton, and Bond Street Beau. It had fitted him like a glove. John Luton, his younger brother, who was Edward’s father, had had no very high opinion of him. He himself had opted for a naval career and had fallen with Lord Nelson in 1805. Edward at that time was already in the Army, a career officer with every intention of staying there. For some years he had continued to hope that Uncle Neddy would settle down, marry and produce lawful offspring to supplant him. This had not happened and by the time that Major Edward Luton metamorphosed into “Mr Frew”, he had given up hoping for it. When Uncle Neddy should pop off, he was clearly destined to step into his shoes. But until then, he had neither the wish nor the inclination to idle about town.

Since his father’s death there had been no-one close enough to Edward Luton to wonder why, exactly, he had accepted the offer that he should take up intelligence work during the Peninsula conflict—though perhaps that had been merely a matter of duty. And certainly no-one to wonder why on earth, after 1812, he should have remained in that service. It required him to mix with what could have fairly been called the scaff and raff of humanity—Major Martin having been a case in point—and, though it might have helped England to win the war, it was not an occupation that was looked on with any favour by his social equals. Edward Luton was wryly aware that in the case it should all come out, it was only his expectations that would ensure his continuing to be received in the drawing-rooms of England.

Certainly the life suited him down to the ground, requiring as it did considerable application of the intellect, and when out in the field, very quick wits and very quick reflexes; and certainly he did not care all that much for the stuffy drawing-rooms of England and all the social fol-de-rol that went with them. But even the late John Luton, who would have been more than ready to concede that damned Neddy’s sort of life was no life at all for a man with red blood in his veins, would not have been able to understand why on earth Edward John Amyes Luton had continued in the life when there was no good reason to do so. He could have gone back to his regiment and the life of a serving officer. If asked why he had not done so, the man who was now Lord Sare would merely have said, with a shrug, that he had always enjoyed his chosen career. And perhaps that was as close as he himself had ever got to understanding his choice. And then, he had known for years that it could not last. In fact it was a wonder that Uncle Neddy had lasted this long: Edward himself was now forty-four years of age. And it was, as certain persons had lately indicated to him, past time that he was thinking of settling down, taking life seriously, and setting up his nursery.

“You cannot continue in these dreadful rooms, Sare,” stated Lady Murton with horrid finality.

“No: appalling,” agreed Mrs Yonge coldly.

Lord Sare looked at them without much affection. Winifred, Lady Murton, was his eldest sister: a commanding matron who had attempted to boss her siblings all her life. And Annabel, Mrs Yonge, one of his younger sisters, was about as bad. Certainly to judge by the amount of time Tommy Yonge spent at White’s when the Yonges were in town. “I fail to see why I should suddenly metamorphose into ‘Sare’ in the family circle, Winifred, just because old Neddy has popped off. And I have no intention of retaining these rooms. I am only here in order to tidy up.”

“What about Sare House?” replied Winifred in a steely voice, ignoring most of this speech. She was very good at that, was Winifred, and Edward had long since come to the conclusion that therein lay a good deal of her power. For how could you argue with someone who affected to ignore your every utterance?

“Well, it is still full of Uncle Neddy’s damned tenants,” he said on an apologetic note.

“Get rid of them, for God’s sake!” said Mrs Yonge impatiently. “You have a position to maintain!”

“So, one would have thought, did he. And it did not seem to bother him.”

“Rubbish,” said Mrs Yonge majestically.

“Quite,” agreed Lady Murton.

“Would these bachelor chambers be acceptable for a mere Mister?” wondered Lord Sare in a musing tone.

The musing tone should have warned the two who had known him all his life. However, Lady Murton, not accustomed to being contradicted or opposed in her own household, rushed in without pausing to think. “No. Besides, you are not a mere Mister.”

“True. Well, if the rooms aren’t suitable for a mere Mister possibly I should not think of passing them on to Jimmy, after all.”

Jimmy Murton was Lady Murton’s second son. She turned purple. “That is not amusing, Sare.”

“Oh, I assure you it was not meant to be, Winifred.”

“Pray do not be impertinent. Jimmy does perfectly well under his parents’ roof.”

Lord Sare said nothing.

“Have you given the tenants notice, Edward?” demanded Mrs Yonge.

“Yes, Annabel, I have,” he said sweetly, “but pray do not imagine that that will ipso facto give you a licence to redecorate Sare House for me.”

“It has never had a thing done to it since—”

“Since Queen Anne, very probably: no. I have no objection to Queen Anne furniture, Annabel.”

Mrs Yonge’s considerable bosom swelled. “You are insufferable, Edward!”

“So you have always informed me.”

“Annabel, he is doing this on purpose to distract us,” warned Lady Murton grimly. “We are here to have a serious discussion, Sare.”

“Yes?” he said politely.

Lady Murton turned purple again, but with a visible effort restrained herself. “You are very well aware that it is past time that you should be setting up your nursery. Unless you wish our second cousin Vincent to inherit?”

The considerable number of tenants, the large number of estate workers, and all the other dependants of the Luton family would have suffered considerably under Vincent Luton’s reign, as Edward was very well aware. Not that Uncle Neddy had given a damn about them: but he had at least had the sense to leave Sare Park and the rest of the extensive country properties in the hands of a reliable agent. Not giving a damn, either, what was spent on the estates. In consequence the house and outbuildings of Sare Park were in excellent repair, the fertile Dorset lands in good heart, and the tenants prosperous and happy. Vincent Luton, on the other hand, was a mean fellow who would have begrudged every groat spent on the upkeep of his inheritance. Lord Sare therefore replied: “No, I don't.”

“Well, then?” demanded Mrs Yonge.

“I thought we were in mourning for Uncle Neddy? I can hardly rush round doing the pretty to acceptable young maidens in my blacks.”

“That is not amusing,” stated Mrs Yonge grimly.

“What about Miss Seaton?” demanded Lady Murton.

“She is not amusing, either, alas, Winifred.”

“Sare, you will go too far,” she warned.

Lord Sare got up. “Not with Miss Seaton, I assure you most sincerely.”

“That is beyond the pale!” cried Mrs Yonge loudly, springing up.

“I see you are ready to go,” he replied courteously. “Allow me to get the door.”

“Sit down, Annabel!” ordered Lady Murton loudly.

“But—”

“He may be as rude as he cares, he will not distract me. Miss Seaton, as I am sure you know, Sare, has been in expectation of an offer any time these past eighteen months.”

“Goodness; and she is still hanging on?” he murmured.

“Winifred, for Heaven’s sake! He is insupportable!” cried Mrs Yonge.

“Then go, if you wish. I intend to say my piece.”

Looking very uncertain, Mrs Yonge sat down again.

“She is an extremely suitable woman, and our families have known each other forever.”

“It does seem so, yes,” agreed her brother.

Lady Murton gave the empurpled Annabel a warning glance. “Certainly she is not in the first blush of youth, but a man of your age should not be looking in the nursery for a wife.”

“No, indeed, quite ineligible,” he murmured.

“Sir William and Lady Seaton are in expectation of your offer,” she warned.

“What you mean is, Winifred, you and your bosom-bow, the Seaton woman, have cooked it all up between you. May I remind you of two points? The first is that the Seatons are country nobodies. And the second is, that I had nothing to do with any notion of a match between myself and Miss Seaton. I shall write myself to inform Lady Seaton of the fact. And if you wish to be invited to Sare Park, Winifred, I suggest you take this with a good grace.”

“How DARE you?” she shouted, heaving herself to her feet.

Lord Sare went over to the door. “Winifred,” he said calmly, “I have scarcely laid eyes on you these past twenty-five years, except on the odd occasion when you needed me to make up a dinner table. Now that I have inherited the damned title, I suppose I owe it certain obligations, one of which is to invite you and your brood at suitable intervals. But just bear this in mind: I do not particularly consider that I owe you, yourself, any duty. And that most certainly applies to you also, Annabel; I can count on one hand the occasions on which you have had me to dine at your house.”

“What you MEAN is,” shouted Annabel, tears starting to her rather protuberant blue eyes, “that you are going to let that Pusey woman decorate Sare House for you! And rest assured that Tommy and I shall never set foot in it, if you do!”

“Well, no,” he murmured. “I have recently discovered that Lady Pusey’s affections are not—er—exclusively mine.”

“Since were are being so frank, Sare,” said Winifred grimly, gathering her wraps about her, “let me say that you must be the last person in London to have become aware of that fact! Added to which, the woman only threw herself at you because she knew you were in line for the title.”

“No, did she?” he said in horror.

Lady Murton drew a very deep breath and marched over to the door. “Come, Annabel. –I trust you will think better of your intemperance, Sare. I shall await your apology.”

“For myself,” said Annabel grimly, “I care not if you apologise or not!”

“Well, that is a pity; I quite like old Tommy,” he murmured, bowing slightly and opening the door.

His sisters swept out without another word or glance.

Lord Sare shrugged slightly. He had been about to pack his books when they interrupted his morning. He got on with it.

Mrs Luton blew her nose. “I cannot see why I should not call myself Lady Sare.”

“You were never married to Lord Sare, Mamma,” replied her son indifferently. –He had seen little more of the lady who wished to be known as the Dowager Lady Sare, these past twenty-five years, than he had of his sisters Winifred and Annabel. Mrs Luton had a pleasant house of her own choosing in Kensington. Her widow’s portion could well have paid for its upkeep; nevertheless she had left that duty to her only son. Edward had not complained. But if he had expected that he might in return be invited to dinner parties, little soirées, and so forth, at his mother’s house, he would have been disappointed. Having known her all his life, he had not formed any such expectations. It was not that Mrs Luton, at the time of John Luton’s death at Trafalgar, had been at all invalidish. But she was not interested in any form of pleasure except that of complaining of her lot, her neighbours, and life in general. And most certainly not in that pleasure which consists of giving pleasure to others by means of dinner parties, little soirées, and so forth. When he was in London, Edward paid her a duty visit once a week. During these visits she did not listen to a word he uttered, complained unceasingly of her lot, her neighbours, and life in general, and very often neglected to offer him so much as a cup of tea. She was, of course, an elderly woman, now; but as her wits were as sharp as they had ever been, had not the excuse that they might have been wandering. Whether she did not care if he drank tea or not, or whether she was simply too mean to offer, Edward had never decided.

In the earlier days of her widowhood he had conscientiously attempted whenever he was on leave to take her out to dine or to the theatre. She had rarely accepted: such mild pleasures did not interest her. He had sometimes wondered why Nature had bothered to create such a creature, let alone endow it with such long life. For if life was not meant to be lived to the full of one’s capacities, what on earth was it for? Some might have said, for the performing of one’s Christian duties; but Mrs Luton did not occupy herself with charitable work. She considered that the poverty of the lower classes was the result of laziness alone, and that those who were not willing to work to improve their lot were not deserving of our pity. It was not an uncommon attitude, true. And as it often was, was accompanied in Mrs Luton by an apparent incapacity either for counting one’s own blessings or for wondering why, in that one did not oneself either reap or sow, one had been spared the curse of poverty.

Mrs Luton blew her nose again. “In any case, I think I should remove to Sare Park.”

Lord Sare did not think so. “Of course I shall invite you at intervals, ma’am.”

The handkerchief fluttered to the ground. “What do you mean, Edward?”

“Precisely what I say. I shall be entertaining a considerable deal. Of course, should you wish to act as my hostess, we might come to an arrangement.” –This was a deliberate gamble. He waited calmly.

“At my time of life?” she said faintly. “It is not to be thought of.” There was a short silence. “Er, what do you mean, entertaining a considerable deal?”

“Large house parties,” said Lord Sare on an indifferent note. “Shooting parties, that sort of thing. Not upwards of fifty persons at a time, I should suppose. Though there will be larger dinners for the neighbourhood, of course.”

“Fifty— I could not possibly, in my state of health,” she said faintly.

Apart from a little stiffness in the joints, she was as healthy as a horse. “No, quite, ma’am,” he said politely.

Mrs Luton looked sadly down at her handkerchief.

“I do beg your pardon,” said her son. “Allow me.” He rose, bent gracefully, and retrieved it. “With your permission, I must take my leave; I have considerable business to attend to.”

“Wait, Edward!” she cried as he reached the door. “What about Sare House?”

He turned. “I am in the process of endeavouring to evict the tenants whom Uncle Neddy put in—unwisely, I fear. Though his reluctance to live in the place is understandable.”

“Tenants? What do you mean?”

He was not altogether surprised to realise that she had not heard. Although given her normal attitude to the utterances of her descendants, very possibly Annabel had mentioned it, and she had simply not listened. “Tenants. I think he is a retired merchant or some such.”

“In the town house?” she gasped.

“Mm. Smacks of lèse majesté,” he murmured. “I must go.”

“But wait! You must arrange for me to remove to Sare House the instant they are out of it!”

“Certainly, ma’am,” he said colourlessly. “I shall be glad to have you superintend the redecorations.”

“Superintend the— What can you be thinking of, Edward?” she said faintly.

Principally he was thinking that a cup of tea would be quite welcome at this juncture. “I am thinking that after fifteen years or so of tenants, the town house is undoubtedly in need of considerable refurbishing. And as Annabel tells me it has not been touched since the days of Queen Anne, I have decided that thorough redecorations are in order. As soon as they are well in train I shall be able to commence entertaining.”

“You have never entertained in your life,” said Mrs Luton faintly.

He did not see, precisely, how she would know. Though certainly he had rarely been permitted to entertain herself. “I have never before been Lord Sare in my life. Sare House will certainly be in want of a competent hostess. I had envisaged that my wife would fill that rôle, but if you should care to do so in the meantime—?”

“I could not possibly; the very idea is absurd,” she said faintly, lying back in her chair and sniffing her vinaigrette.

“Blefford Square is certainly a noisier situation than your present one,” he owned detachedly.

“There would be carriages coming and going all night,” said Mrs Luton faintly.

“Very probably. I believe that the Bleffords do entertain a great deal, and then, Stamforth House is in Bl—”

“That Portuguese woman,” stated Mrs Luton grimly.

“Lady Stamforth? She is entirely charming. They hold a lot of parties.”

“It is not to be thought of,” she said, closing her eyes.

He was entirely of that opinion. “Quite. I shall see you next week, Mamma. Good-bye.” Mrs Luton was still lying back with her eyes closed but he bowed, and went out.

It was not until some considerable time had passed and Mrs Luton had revived sufficiently to have a tray of tea brought in for herself, to deliver a long complaint to her parlourmaid, and to sip the tea and consume a considerable amount of cake, that she blinked and said dazedly: “His wife? What on earth—?” By which time, of course, it was rather too late for enquiry.

“Uncle Edward is entirely ruthless!” concluded Mercy Hartwell with a giggle.

Lucasta, Lady Hartwell, Mercy’s Stern Mamma, also gave a giggle. “And always was! I would I had been a fly on the wall when he routed Winifred!”

“And Aunt Annabel!” she agreed.

“Mm!” squeaked Lucasta. Forthwith both Hartwell ladies collapsed in gales of giggles.

Lucasta Hartwell, who had been Lucasta Luton, was the youngest of Edward Luton’s sisters. She had married very young; possibly, as Lukey herself was wont to claim, the consequence of having been launched into Society from the grim Winifred’s house. As a result, there were but seventeen years between herself and her oldest child, Philip, and a bare nineteen between the seventeen-year-old Mercy and her Stern Mamma. Lukey Luton had never been a beauty, so it was astounding to not a few of her contemporaries that she had managed to capture Viscount Hartwell. Quite a catch: if the title was nothing like as old as that of Sare, it was old enough, and considerable properties went with it. The Viscount had been a lot older than Lukey, the daughters of his first wife in fact being her elders; and that such an earnest, responsible member of the House of Lords should have wanted Lukey Luton was perhaps the most surprising thing about the match. Or so Lukey’s friends, giggling terrifically in corners over it, had maintained. Heads somewhat older and wiser than those of Lukey’s very young contemporaries had seen perfectly well what the attraction was: Lukey Luton was one of those gay, laughing creatures who are so full of the zest of living that it matters not what their actual features be. In the case of Lucasta Hartwell, née Luton, the features were small, slightly crooked, and habitually wore an impish expression; and the mid-brown hair, about the same shade as her brother’s, though not yet starting to silver at the temples as Edward’s was, clustered in a wild mass of small ringlets which her Ladyship was wont to bundle under her bonnet scarce combed, on the one hand, or to spend hours and guineas on, on the other hand, depending on the occasion. Though not all grand occasions could reliably expect to see the intricately coiffed version of Lucasta.

Lord Hartwell had died after fifteen happy years of marriage: Lukey had alternately teased and flattered him, the which had appeared to suit the staid Viscount very well. Young Pip, at nineteen years of age, was now the nominal head of his house, although in reality there was such a tribe of doting uncles, affectionate cousins, fond aunts and half-sisters, and so forth, that he could probably have lived out his life quite happily without ever having to make a decision for himself. Likewise the widow: in her case they were doting brothers-in-law, affectionate cousins, fond sisters-in-law and step-daughters. All of whom treated her like a wayward but beloved child.

Mercy Hartwell in looks was much prettier than her Stern Mamma; the glossy brown curls were well controlled, and the small, neat features were regular, with large grey eyes and a sweetly-bowed mouth. She was a sunny-natured, happy girl with a natural charity; but she had not her mother’s impish, wayward, half-laughing, half-plaintive charm. And was possessed of far more common sense than she. The which, as most of Lukey’s contemporaries recognised, was just as well. Imagine two of them, and Lukey in charge of one!

The sad truth that not all daughters of charming mothers adore them did not hold good, in Lukey Hartwell’s case: her children adored her unreservedly.

“We could,” she now said indistinctly, popping a sweetmeat into her mouth, “ge’ on down to Share Par’ and annoy him horr’ly!”

“Yesh,” agreed Mercy, twinkling at her over her own sweetmeat. “Mm! These are delicious, Stern Mamma!” she said, swallowing.

“From Willy Naughton,” she said, making an awful face.

“Oh, Mamma!” cried Mercy reproachfully.

“Well, they looked irresistible. Have you tried one with a candied violet on top?”

“No. Rozshe petal,” said Mercy through another one.

“I did warn him,” said Lukey lightly, taking another and closing the box, informing it sternly that it was ruining their figures, “that one box of sweetmeats does not an acceptance of a proposal of marriage make.”

Well though she knew her, Mercy choked on her sweetmeat. “You didn’t!” she gasped, as Lukey banged her hard on the back.

“Yes, of course. One could not let the poor fellow,” she said, tilting her head to one side and fixing her with a bright eye, like an impish robin, “labour under a misapprehension.”

Most regrettably indeed, Miss Hartwell collapsed in helpless giggles, gasping: “Mamma, you are too cruel!”

“I do not encourage them to lay themselves and their silly houses in Worcestershire at my feet.”

“You—do—too!” gasped Mercy through the fit.

“Very well, then, I do not force them,” she said airily. “Shall we go round to Edward’s unsuitable rooms and inform him that we’ll accompany him to Sare Park?”

Mercy blew her nose. “Yes, do let’s! –I confess I cannot see why they are so unsuitable in Aunt Winifred’s eyes.”

“Only for Lord Sare, I think, darling. Don’t wear that boring dress, put on something pretty.”

Smiling a little, Mercy went off to change. Mamma had been known absent-mindedly to pay calls in the gown she wore to wash the dogs.

… “Ooh! What a Corinthian sight!” squeaked her Ladyship when they got there.

“I think he looks a guy,” said Mercy, frankly staring. Uncle Edward was in driving dress, the which included a bizarre blue and yellow striped waistcoat and a black-dotted muslin cravat.

“Yes. It is the insignia of the F.H.C.,” he said unemotionally.

“Edward, darling, have you been keeping this a secret from your adoring relatives?” cooed Lukey, fluttering her lashes.

Mysteriously, Mercy collapsed in giggles, gasping: “I’m so—sorry—Uncle—Edward!”

“Oh, I don’t think you need apologise, Mercy,” he said mildly, eyeing his sister without much favour. “Recently elected, though there is no need to excite yourself: the rumour is that the club’s revival has not been successful and it won’t last out the year. And my driving is no better nor worse than it was this time last year. Amazing what the acquisition of a title will do, ain’t it?”

“Oh, pooh!” cried Lukey. “One must be a very good driver, that is the sole crit— um, thingamabob, and of course you are,” she cooed, taking his arm confidingly, and dimpling up at him.

“No,” he said coldly, shaking her off.

“No what?” replied Lukey innocently.

“No, I shall not either do or allow whatever scheme you have in mind.”

“That’s comprehensive!” she said cheerfully, unabashed. “Well, initially, Edward dearest, the scheme is that you should take us in your curricle and four for a little trot. –Strict trot,” she said, making a minatory face at Mercy. “Where is it?”

“The curricle? Potts is walking the horses.”

“Oh, so you have taken on Uncle Neddy’s darling Potts?” she cried.

“Yes.”

“But why did you let the chestnuts go? That hag, Eloise Stanhope, was driving them in the Park only last week!”

“I let considerable of his personal property ‘go’, as you phrase it, Lukey, in order to defray old Neddy’s personal debts.”

“I see!” said Mercy, nodding. “So as the charge of them would not fall on the estates!”

He looked at her with a certain approval in his cool blue-grey eye. “Yes, quite. Well, one of you may come in the curricle, if you wish. But there is not room for both.”

“It had better be Mercy,” decided Lukey. “I may go and buy that hat… But this is not the point! We are absolutely determined to persuade you to allow us to come down to Sare with you, Edward. For it will put Winifred’s and Annabel’s nose so horridly out of joint,” she explained plaintively.

“I think their noses are probably suffering sufficiently already. Why do you wish to come down to Dorset in the middle of the Season? Which of you has blotted her copybook?”

“No such thing!” cried Lukey indignantly. “Mercy is terribly well-behaved, and not in the least like me at that age!”

“That’s good; I actually felt sorry for Winifred.”

Lukey counted on her fingers. “Twenty year agone, does not time fly? You would have been with the regiment.”

“Nevertheless I felt sorry for Winifred. Why do you wish to come to Sare Park?”

“I just think, darling Edward, that Willy Naughton might believe I was serious in refusing his offer, if I was absent for a little,” she said plaintively.

He winced slightly. “I certainly don’t wish to see you married to Naughton. –What is your excuse?” he demanded of his niece.

Mercy blushed. “Well, the Season is very boring, and—and I have never been to Sare!”

“Oh, have you not? –No, suppose not,” he said as Lukey broke into involved explanation. “It’s all right, Lukey; not even you would have desired to take a maiden daughter there in old Neddy’s time: I quite understand. I’m leaving tomorrow morning, at seven.”

“Seven?” said Mercy faintly.

“Mm.” He eyed her ironically. “I know your mother commonly gets to bed around three when the Season is in full flight. I shall call at Hartwell House at seven-thirty. If you are not ready, I shall not wait. Now, do you wish to come up in the curricle?”

“Oh, yes, please, Uncle Edward!” she cried, clasping her hands together.

“Very well, then. –Come along, Lukey: you cannot stay here, the place is full of thick-witted bachelors who would be only too happy to offer you tea, stronger drinks, and their horrible bodies,” he said unemotionally.

Giggling, Lukey confessed that she knew, and it was tempting, but on the whole she thought she had best rush off and buy that bonnet before “darling Gaetana” pounced on it. Noting that it was a great pity Mercy had worn the green, for it would not look at its best with Uncle Edward’s horrible waistcoat and besides, was not driving dress, she dropped a pair of careless kisses on her relatives’ cheeks, and rushed out.

In her wake there was a short silence.

Lord Sare cleared his throat. “Er, did the Spanish reference just now indicate that Lukey is patronising the Marchioness of Rockingham’s milliner?”

“Yes,” said Mercy succinctly.

He winced slightly. “Do me the favour of reminding her that the Hartwell pockets are not bottomless.”

“Well, I shall, but the thing is, she will not take very much notice. Well, she will start off intending to do better and then forget. But if she is in difficulties of course Uncle Dicky or Uncle Johnny Hartwell will bail her out!”

“That isn’t the point,” he said, swallowing a sigh. “Oh, well, better to have doting in-laws than curmudgeonly ones, I suppose. Are you ready? Let’s go, then.” He offered her his arm in a stately manner, and Mercy took it, very pleased to be treated like a grown-up lady by Uncle Edward. –Every feeling was, of course, echoed on her transparent, round, youthful face. Edward’s eyes twinkled slightly but he made no remark at all.

“Fusty,” pronounced Lady Hartwell, wrinkling her charming little up-turned nose.

Her brother swallowed a sigh; she must mean in the metaphorical sense only, for the rooms of Sare Park were without exception clean, fresh and pleasant. He had not for a moment expected to have company on the journey, but to his astonishment they had been ready when he called for them. Mercy had apparently been dispatched to bed early by her Stern Mamma. And Lukey, it emerged after she almost instantly fell asleep in his travelling coach, had managed this astounding feat by the simple method of not going to bed at all.

“We could do a lot with it, though!” she added brightly.

“You are not being given the chance, Lukey,” he replied immediately.

“Oh, pooh! Or are you proposing yourself to choose fresh curtainings and chair-covers?” she cried gaily.

“Well, no.” He eyed her drily. “It requires a person of taste, I would say.”

“If that is a reference,” she said, putting the nose very high in the air—or as high as was possible: Lukey came barely to Edward’s shoulder—“to my Egyptian salon—”

Regrettably, Miss Hartwell here broke down in helpless giggles.

“Yes,” said Edward with considerable pleasure when she was over them. “Your Egyptian salon is known to the whole of Society as the greatest mistake since—let me think… Castle Howard.” He gave her a very dry look.

At this Lukey also broke down in giggles, though owning when she was over them: “That was the most unkindest cut of all!”

“Is Mamma’s salon worse than the Brighton Pavilion, then, Uncle Edward?” asked Mercy with bright-eyed interest.

Edward’s long mouth twitched but he admitted: “I rather like the Pavilion. It has… unabashed eccentricity.”

“I see. While my salon has merely poor taste,” said Lukey with immense gloom.

Lord Sare did not apologise grovelingly, as any of Lukey’s very numerous admirers would have done. “Quite.”

“I was much, much younger then!” she said eagerly. “Oh, could I not? Please?”

“Pink would be pretty in this room,” murmured Mercy, looking around the gracious downstairs salon, with its long windows opening onto a terrace.

Lord Sare winced slightly but said nothing.

“Darling, you always like pink,” reproved Lukey cheerfully. “I agree it would be pretty, but a gentleman does not want pink for his downstairs salon.”

“What about that horrid dark gold room upstairs that you said might be Lady Sare’s boudoir?” she said eagerly.

“Why, yes! Hang the walls entirely in… Not pink brocade: too obvious,” she said, narrowing the little bright eyes. “Pink silk. Watered silk?”

Mercy clapped her hands, so evidently the fate of Edward’s non-existent wife’s putative boudoir was settled.

“In the first place, I do not have a wife as yet, and in the second, what if she were to have bright ginger hair?” he murmured.

“Ugh!” cried Lukey, shuddering. “You would never choose a wife with bright ginger hair, Edward; do not be absurd, pray!”

“Auburn, then: à la Lady Rockingham,” he murmured.

“Gaetana is a delightful creature and entirely sympathetic, but if you imagine a woman of her type would be able to support you for more then a se’en-night, you are quite out, I assure you,” responded his sister calmly.

“Mamma!” uttered Miss Hartwell, turning the sort of bright pink that definitely would have clashed with ginger hair.

“What is wrong with me?” asked Lord Sare calmly.

Lukey’s clever little eyes narrowed. “Too… coldly calculating. And horridly matter-of-fact.”

“Er—Rockingham is not matter-of-fact?” he murmured, apparently not at all put out.

“Don’t be silly, Edward. He is the most sensitive creature, under that bluff exterior he apparently feels necessary to assume in the company of you silly males. No-one who plays the pianoforte as angelically as he could possibly be matter-of-fact.”

“Oh, dear. I fear it is too late for me to take up the instrument, for they say it takes years of practice, preferably in infancy. But mayhap I could try something smaller? The piccolo?”

Mercy collapsed in giggles again.

“You are being silly,” said Lukey sternly, trying not to laugh. “Just concentrate! What colour would you prefer for this room? See, it has the most delightful proportions! Just imagine it without all this horrid brown stuff.”

“I would call it olive, in the main. Er… I cannot,” he confessed ruefully.

“I rest my case,” said Lukey superbly.

Lord Sare smiled weakly. “Mm. But all this furniture is still good—”

“I meant, re-cover it only!” she said swiftly.

“Yes. The coverings are quite good, Lukey. And that odd-looking—” He cleared his throat: that had come out of its own accord. “That unusual-looking set of sofa and chairs over there has embroidered covers.”

“Tapestry-work, my dear. Hideous.”

“It is very strange,” allowed Mercy. “Is it supposed to show a Chinese influence, perhaps?”

Lord Sare rubbed his chin. “Er, well, possibly. The thing is, Lukey, we should not decide to get rid of anything until we have determined what is properly to be classed as a family heirloom.”

“Edward, no sane family would desire to retain such pieces!”

Mercy was examining the sofa. “The work itself is very fine. Look, there are two ladies going over a bridge! Or is it a lady and a man? –I must admit the colours are horrid. I do not admire this mixture of yellow and green.”

“No, and it is all faded horridly,” said Lukey briskly. “Those pieces are not heirlooms, Edward.”

“And would look delightful in pale pink watered silk,” he said drily.

“Yes!” gasped Mercy. “So they would! Mamma, we could transport them to the boudoir!”

“Just listen to me, before you get carried away, Lukey,” said Edward loudly over the subsequent discussion. “You are not to take it upon yourself to order up curtainings, hangings, or any sort of reupholstery, re-covering or refurbishing at all for Sare Park. Is that clear?”

“No!” she cried crossly, flags flying in her cheeks. “For if I do not do it, who will? Are you proposing Winifred, perchance? Or Annabel—she would leap at the chance! Or Mamma?” she ended with horrid irony.

“No,” he said calmly. “I have in mind a woman of perfect taste to advise me.” And on this cool utterance he walked over to the long windows and went out.

Mercy was heard to swallow loudly. After that there was a considerable silence in the well-proportioned but tastelessly appointed downstairs sitting-room of Sare Park.

At long last Mercy faltered: “He—he did not mean that horrid Lady Pusey, surely?”

“No. He would not foist the creature upon the family home,” said Lukey definitely.

“No. Good,” she owned. “Wuh-well, who, Mamma?”

Lukey frowned over it. Finally she produced: “No-one. I believe he said it to annoy: it would be just like Edward!”

Mercy smiled weakly, but did not argue. It seemed all too like Uncle Edward, indeed.

“I had heard,” said Mr French politely, “that Sare Park itself was empty.”

“No,” replied Mr Solly baldly. Mr Solly, who was Lord Sare’s agent, was deeply suspicious of this Mr French. Mr French’s refined accents signified very little, in Mr Solly’s opinion. And his neat dark coat and grey pantaloons signified that he had no notion of how a gentleman dressed in the country. –Mr Solly himself was of course wearing breeches and boots.

“Pity,” said Mr French calmly. He was aware of Mr Solly’s suspicions and silently amused by them.

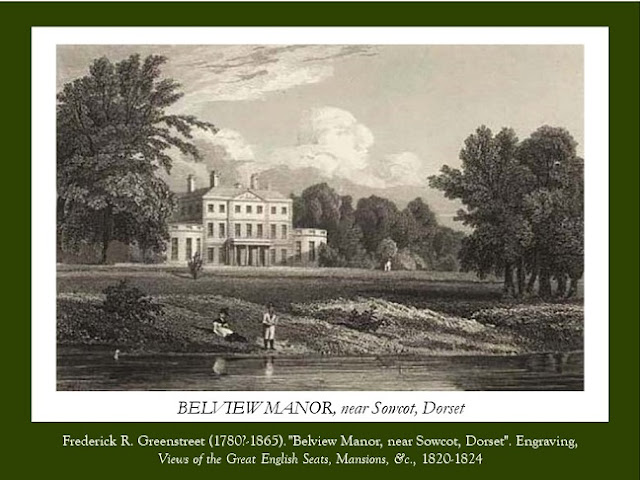

“Belview Manor is empty,” said Mr Solly helpfully.

Mr French had seen this property, and so knew that in the first place it was not a manor nor anything like it, and that in the second place its name must be wholly spurious, for it had been built a mere fifty years back to house a sister of the then Lord Sare and her family. “No. Too small,” he said bluntly.

“Er… There is Little Sare. It needs a considerable amount of work done to it,” said the agent cautiously.

“So I would suppose,” said Mr French calmly. “How old is it?”

“How old?” Mr French just looked at him blandly, so the agent concluded he really did wish to know. “Well, the original structure was built in the days of Queen Elizabeth. During the last century there was a considerable amount of upkeep done. The rooms are quite modern and comfortable, though the Elizabethan style has largely been retained.”

“I see. What about during this century?”

“The roof is sound, sir,” said Mr Solly on a note of offence.

“I was thinking more of the creepers on the outside and the forest surrounding it.”

“The last tenant was a man of eccentric habits, sir, who preferred his privacy.”

“If you say so. I’d want the creepers off immediately and the whole of the brickwork repointed and every chimney in the place thoroughly checked. The drive regravelled, too. And if that front gate can be fixed, fix it. Otherwise put in a new one. We can leave the pointing of the boundary wall until later, but I’d want that forest felled and new turf put down before I moved in.”

Mr Solly attempted to argue, largely on the score of the forest’s having originally been a shrubbery, but was ignored. Mr French stated those were his terms, and what was he asking? Mr Solly warned him that the normal practice was a year’s rent in advance and a long lease. Mr French advised him that he might hang out for that, then, and made as if to rise. Mr Solly assured him that it might be possible to come to an arrangement, and Mr French duly sat back. Though with a very dry look in his eye, of which, perhaps fortunately, Lord Sare’s agent was not aware.

“Well, my dear?” asked Mrs Solly, later that day.

“He took Little Sare. Said Belview Manor was too small.”

“He must be a gentleman, after all!” she gasped.

Mr Solly tugged at his boots, looking annoyed. “No. If you ask me, he’s a Jew.—JOHN ADAMS!—Wouldn’t let on what he does, just said he was used to be in business. And he made me draw up a damned great agreement as long as your arm, making sure I put in that the boundary wall would be repointed!”

“But Nicky, you were intending that, anyway,” she said feebly.

“Told ’im that,” he grunted. “Don’t think the fellow believed me. –Just wait until Pa hears about that!” he warned.

This personage was Mr Solly’s predecessor in the post of agent to the Barons Sare, and most certainly nothing like an ungentlemanly tenant who refused to take a man’s word that his wall was due for repointing had ever been heard of in his day. Mrs Solly nodded feelingly.

“There you are,” said Mr Solly with a sigh as John Adams panted in. “Get these boots off me, man, for the love of God.”

John Adams obligingly bent and tugged.

“Did he look like a Jew, Nicky?” asked Mrs Solly.

“Uh—well, nothing to put your finger on. Just looked like a merchant. Well, prosperous, you know. Only the thing is, where else am I going to find a let for Little Sare? The district,” said Mr Solly crossly, “is too obscure!”

“Yes, and people don't want Elizabethan houses, these days.”

“It is very comfortable. Several of the original rooms were thrown together, during the last century.”

“But the ceilings are so low. I like a nice modern house. White, with pillars. Though Belview Manor is pretty, too.”

“With a porch with pillars,” said Mr Solly, smiling, as she presented him with his slippers. “Thank you, my dear. –Bring a jug of spiced ale, John Adams, if you would.”

“Spiced ale? It is such a mild day, and almost May!” objected Mrs Solly, though with a smile, as John Adams, grinning, hastened out.

“I need it. –I would bet my stockings,” said Mr Solly: it was an expression of his father’s, very popular in their sleepy little Dorset district, “that he is a Jew.”

“Will Lord Sare be cross?” she faltered.

“Shouldn’t think so. Not if the fellow pays up. Well, he paid two quarters in advance,” he admitted.

“Oh, well done, dear!” she cried, clapping her hands.

Mr Solly gave a gratified smile. “Thank you, Mary, my dear. Added to which,” he noted, leaning back at his ease in his big chair, “I shan’t tell him. The fellow looks respectable enough. Dare say he might pass for a gent.”

“Well, I have to say this, Nicky, dear,” said Mrs Solly comfortably, taking up her stitchery, “if he cannot, the neighbourhood’s noses will be very much out of joint. For say what you will, Little Sare has the name.”

“Not much land attached, though. No, well, Lord Sare told me to let it to anybody who seemed respectable and could pay a decent rent. He don’t care about Ma S., or Miss P., or even Lady B.!” he said, winking.

Sad to relate, at this Mrs Solly, who was not considered by these highly respectable neighbourhood personalities to be a lady or anything near it, collapsed in awful splutters.

“Does he have a family?” enquired Lady Bamwell, at her most majestic.

Miss Pinkerton blinked. “Er, well, no, Lady Bamwell, did we not just say that he is a bachelor?”

“Good gracious, Miss Pinkerton, not Lord Sare!” replied Lady Bamwell, looking down her substantial nose at her. “The new tenant of Little Sare.”

“Your wits must have been wandering, Aunt,” explained India Hutton primly. Miss Pinkerton gave her a warning glance, and Miss Hutton continued calmly: “Mrs Solly mentioned to us, Lady Bamwell, that Mr French had told Mr Solly that he was a widower with two children. Though he did not mention the age of the children.”

“But as he is a man of middle years, I dare say they may be quite grown up,” added Miss Pinkerton.

Lady Bamwell’s eyes just flickered over the person of Miss Hutton. Seven-and-twenty years of age and still unattached. “Mm. Let us hope so. Our district could certainly do with some new young people.”

Miss Hutton opened her eyes very wide. “Why, yes! And then perhaps we may start up the assemblies again!” She clasped her hands to her flattish bosom, and sighed affectedly.

…“India, dear, I really must beg you not to provoke Lady Bamwell,” begged Miss Pinkerton somewhat limply as the two made their way back to her sufficiently obscure Dove Cottage—on foot, they did not possess a conveyance and Lady Bamwell had not offered one of hers.

“Dearest Aunt,” replied India, hugging the maiden lady’s thin arm into her side, “she is too full of her own consequence to notice when one is committing the crime of lèse majesté.”

Miss Pinkerton gave a squeak and a muffled giggle, but shook her head at her, as they approached the outskirts of Sowcot village. –The name was maintained by the local vicar, who was a considerable scholar, to be a corruption of “Sarecot”, the “cot” meaning dwelling-place, as in “dovecot”. India Hutton, who had not the Reverend Mr Bigelow’s scholarship but possibly more common sense, maintained to the contrary that the reference was to the local habit of raising swine. Of which there was certainly a profusion, the ground in those parts being extremely fertile and allowing of the production of almost any fruit, vegetable or beast one cared to name.

Sowcot was very small and sufficiently obscure, tucked away a few miles from the Dorset coast about midway between Weymouth and Swanage, but it had the inestimable advantage of being surrounded by some very choice properties indeed. Or so it was Lady Bamwell’s custom to maintain. Of which Bamwell Place, according to herself, was not the least. The late Sir George Bamwell, Bart., a man whom India Hutton never was able to picture with success, in especial the actual proposal of marriage, had been wont to call himself “the squire”, and had been the M.F.H., and apparently quite a popular figure in the district. His son, Sir Bernard, who was extremely popular, nay, adored, in the district, and ardently pursued by anything that could possibly lay claim to débutante status, would never have dreamed of calling himself the squire. He had publicly disclaimed any wish to be anything like M.F.H., too, donating all his father’s prized hounds to a Mr Sardleigh, who did have that wish but had never expected it to be gratified while a male Bamwell was above ground. Bernie Bamwell, as he was known to most of the county and to innumerable cronies in London town, was only twenty-three years of age. Blue eyes, black curls, a laughing red mouth, and a caressing manner. And might, at least according to his mother, have taken his pick of the highest-born ladies in the land.

Mr and Mrs Sardleigh also owned what Lady Bamwell considered a very choice property. In fact Lady Bamwell considered it would a very appropriate adjunct to Bamwell Place. Though of course dearest Bernie could look much higher for a bride—much higher. High Oaks had originally been a mere farm but towards the early part of the previous century the property had been let go out of the Luton family—unwisely, according to some—and a handsome house built upon it by the present Mr Sardleigh’s grandfather. With, according to some, his wife’s money. His son had certainly married well, that is to say married a lady with thirty thousand pounds, and the present owner had continued the tradition. The current Mrs Sardleigh had brought her spouse ten thousand pounds a year and a personality as sour as crabs. She and Lady Bamwell were naturally on terms of dearest enmity.

In addition to these two choicest of properties there were, of course, Belview Manor and Little Sare, both of which were quite near to Sare Park, and, on the far side of Bamwell Place, Godley Hall, tenanted by a Mr Groot and his family, and the smaller but still very respectable properties of Quayne House (the Yelbys), Felldene (the Knightons), and, on the coast itself, The Heights (the Dunnes). So, quiet though it was, it was quite a little neighbourhood, really, and it was a great pity that all of these houses were not bursting with young people who might have attended the assemblies in Sowcot which, as India Hutton’s recent reference had indicated, had had to be discontinued.

Miss Hutton would, in fact, if tortured with something appropriate like hot irons, have admitted that she had not the smallest desire to adorn an assembly, in Sowcot or otherwise. Not even for the privilege of dancing with Bernie Bamwell! Miss Hutton was an orphan, her papa having fallen at Waterloo, and her mamma, not a young woman, having been carried off in the severe November weather five months back. True, Miss Hutton had other aunts and uncles than Miss Pinkerton, and even a pair of married sisters, both considerably older than herself and in comfortable circumstances. These ladies had warmly offered her the post of unpaid nursemaid-cum-governess and general drudge to themselves and their households but astoundingly, India had turned them down in favour of a quiet life with dearest Aunt Beatrice. She had had a Season, of sorts, in Dorchester, but as Waterloo had intervened, this had never come to anything. Mrs Hutton, the period of her official mourning being over, had been in too depressed a state to suggest another, and India, discovering with horror the amount of Papa’s debts and the insufficiency of a lieutenant-colonel’s widow’s pension for settling same, had not ventured to prompt her. Seasons could go hang: they would be lucky not to end in the Fleet Prison! Added to which, what were Seasons to India? She was by far too old-cattish to snare a pretty young husband, and having no fortune at all, could not hope to snare an ugly elderly one.

Miss Pinkerton, to whom this opinion had blithely been confided, had looked very distressed and patted her hand, assuring her that she was not old-cattish at all; but India had just laughed. She was a tall woman, with a mop of uncontrollable hair of a singularly odd shade, almost a pale bronze, which she customarily wore wound into stern bands, the which proceeded to turn frizzed and untidy the moment she turned her back on her mirror. Her face was, she supposed, well enough: but wide mouths and pronounced cheekbones were most definitely not in the mode: the fashion was all for round or oval faces, tiny bowed mouths and sooty dark eyes. India’s eyes were an odd greenish shade, even greener than her peculiar hair. (Hazel, according to the kind-hearted Beatrice Pinkerton.) Over the nearly nine years since her father’s death she had not, whether from grief or straightened circumstances, managed to eat very well: the tall figure was thus very angular indeed. Miss Pinkerton was silently determined to feed her up. They had eggs a-plenty, and good Dorset cream and butter, and she was quite sure that dearest India might be as great a beauty as her own dear Mamma had been! India had laughed and kissed her cheek, and kindly not pointed out that her late maternal grandmother had been considered by her very grand family to have thrown herself away on a mere Mr Pinkerton of nowhere in particular and that the said grand family had never bothered to receive Lady Charlotte Pinkerton again. Nor that, even if she should metamorphose into such a beauty, there was still no hope at her age of catching a pretty young fellow, and, one’s face not generally being considered one’s fortune at turned seven-and-twenty, no hope of an old and ugly one, either.

“Well,” said India cheerfully to her aunt, “shall we go straight home? Or call on Mrs Sardleigh, in the hope of being the first to annoy her with, pardon me, gladden her heart with, the news that Little Sare is let to an unknown suspected of being a merchant?”

“He may be a wealthy merchant, with a son,” Miss Pinkerton reminded her primly.

“Yes!” she gasped. “Who will be overcome by the mere sight of Miss Sardleigh, Miss Primrose Sardleigh and Miss Daphne Sardleigh, and offer them his hand, heart, and expectations on the spot! –Severally or collectively.”

“Yes, quite. Well, they are very pretty girls, my dear.”

“Certainly. And it is not their fault if Sir Bernie Bamwell appears not to know they are alive,” she agreed earnestly.

“Well, no. Nor Mrs Sardleigh’s, either,” conceded her aunt drily.

Their eyes met. India collapsed in helpless laughter. Miss Pinkerton produced a spotless handkerchief and sniggered behind it in a refined manner.

“So shall we?” said India eagerly.

“Er—well, I could fancy a cup of tea first,” she said on a weak note.

“What a wise precaution,” agreed India primly. And forthwith the two ladies adjourned, arm-in-arm, to tiny Dove Cottage. –It did possess a dovecot, yes, The which did not, however, make Miss Hutton the more inclined to believe a word of the vicar’s etymology.

“Very possibly,” noted Mrs Sardleigh, passing the cake, “Sare will patronise the assemblies.” Mrs Sardleigh was, of course, the sort of woman who refers to persons of title with whom she is not acquainted by the proper name in the title alone.

What made her think this, was beyond the capacity of India Hutton and Beatrice Pinkerton to imagine. They nodded politely, however, and eagerly accepted large slices of excellent fruit-cake. It was not every day that they got such, by any means, for Miss Pinkerton’s oven was not entirely reliable and nor, alas, was Miss Pinkerton’s Mrs Stott.

“His sister, Lady Hartwell, is with him, of course,” noted Mrs Sardleigh in a careless voice.

How did she know such things? There was no doubt that her information was customarily correct, however, and the visitors nodded eagerly and waited for her to tell them just who Lady Hartwell was.

“Will Lord Sare stay, do you think, Mrs Sardleigh?” India then ventured.

“On this occasion? Scarcely, Miss Hutton. The Season must still be in full swing, you know. I dare say he has come down merely to assure himself that the house will be in order for him this coming summer.”

“So, um, does he intend to be here for the summer?” fumbled India.

Mrs Sardleigh ate a minute piece of cake. “I really have no notion, my dear Miss Hutton. I am not acquaint with Sare.”

… “One cannot win!” declared India angrily, as the visitors, in a duly chastened mood, retreated. Mrs Sardleigh had of course already heard about the new tenant of Little Sare.

“Well, no,” murmured Miss Pinkerton. “You should not hope to, my dear India.”

“No!” admitted India with a laugh. “Her spies are everywhere: it is well known! –It would be delightful,” she noted dreamily, “if Mrs S. were to arrange an huge and elaborate dinner party for ‘Sare’, which he refused to attend.”

“Yes, but then she would be unbearable all summer, my dear; would it be worth it?”

“She is fairly unbearable anyway,” noted India.

Miss Pinkerton, said to relate, was driven to hide her face behind her handkerchief again.

“Nous voilà,” said Mr French in the language with which his children had grown up.

“En effet,” agreed Mr Gerard French, goggling out of the window of the coach. “Voilà, tu vois? La forêt qu’il nous a décrite!” he said to his sister with a laugh.

“Parle anglais,” reproved Miss French, peering. “O, là,” she noted deeply.

“Yes, speak English,” agreed Mr French, recollecting himself. “Or the neighbours will snub us even worse than they are intending.”

“Are they intending, Papa?” asked Miss French, fluttering her eyelashes very much.

“Undoubtedly. You know the English gentry. –That damned fellow will cut that forest down, or my name is not George French!” he declared loudly.

“Is it?” murmured Mr Gerard.

Miss French collapsed in gales of giggles.

“Ta gueule, Gérard,” said his father genially, directing a friendly punch in his direction. “It’s a solid English name: why not? No, I beg your pardon, my dears. It was, once, actually. Before I met your maman. Well, Grandpère had no sons, and if he wanted me to carry on the family line for him, why not? Only it wouldn’t do, back in England.”

“Mr Meinhoff,” said Gerard experimentally, pronouncing the name without the H, in the accent to which he was accustomed. “No, you’re right. Sounds like a damned Jew-boy.”

“Quite,” said Mr French, very drily indeed.

“Cher Papa,” said Miss French, nestling up to him and hugging his arm, “you ’ave only to reveal one ’alf—nay, one quarter of your wealth to them, and the ’orrid English pairsons weell be—be— Qu’est-ce qu’on dit?” she said feebly to her brother.

“Fawning, is the expression they used at school,” he replied drily. “It takes the preposition ‘on.’”

“Ah, oui? Très bien. They weell be fawning on you, cher Papa, and begging to be invited to our ’ouse and—and goodness knows what!”

“Begging for a loan, if they’re anything like the frightfully decent fellows at damned Harrow,” noted Gerard.

“Never mind, mon petit, it was only for three years, and you made some worthwhile contacts,” said his father kindly.

Gerard sighed. “Well, worthwhile contacts who tried to borrow my every sou at Oxford, yes.”

“You were digging—c’est ça? Digging the greund,” explained Miss French kindly.

“Uh—preparing the ground, I think you mean, mon ange,” said Mr French.

“En effet? Très bien, mon cher Gérard, you were preparing the greund!” said Miss French gaily.

“Oui, oui, Annette,” groaned Gerard. “—Preparing the ground to become a bankrupt,” he muttered.

“No: to charge the damned fellows enough in interest, that they eventually end up bankrupt,” said Mr French with the utmost placidity.

“Papa, if one could hope it! But how can a fellow like Tommy Rowbotham, what never has a penny to bless himself with, and is into me for three hundred guineas as we speak, ever hope to pay any interest at all?”

“He is related to Sir Cedric Rowbotham, late ambassador to Prussia and a damned big wheel,” explained Mr French.

“You're going to dun him, are you, Papa? That will sit well with doing the country gentleman at Little Sare!”

Mr French just eyed him tolerantly. He had plans for Gerard. “Possibly. –There you are, my dears, you get a good view of the house now. At least the damned fellow has put a load of gravel on the drive and got that damned creeper off the brickwork.”

His children looked at Little Sare without enthusiasm.

“Don’t be like that, my dears. There may be some pleasant young people hereabouts. Possibly Lord Sare may have—well, I think he is a bachelor. But he may have some pleasant young connections.”

Annette snorted.

Gerard noted: “Doubt it. Um—Sare, did you say?”

“Yes. That’s the title. Don’t think the agent mentioned the family name. Heard of the family, Gerard?”

“Um… Oh, yes. The Lutons, Papa.”

The coach having stopped, Mr French was about to get down. He paused. “Luton?” he said neutrally.

“Yes. Tommy Rowbotham was telling me that old Neddy Sare, as they called him, popped off not long since. This new man’s nothing very much; a nephew, I think. Um… Edward Luton: that's it.”

“Edward Luton,” said Mr French slowly. “An Army man, dear boy?”

“I don’t think so, Papa,” said Gerard in some surprise. “As I say, nothing very much. Man-about-town, that sort of thing. Spare fellow at a dinner-party: you know the style of thing. According to Tommy Rowbotham, old Neddy Sare was a great gun. The nephew don’t take after him.”

“Really?” he said, looking very dry.

Gerard grinned. “Yes, well, he may be worth knowing, at that! Anything Tommy approves of is bound to be the most utter shag-bag, if he ain’t a positive Captain Sharp! Oh; said he could handle a sword: saw him fence once at old Fioravanti’s.” He shrugged. “I know no more.”

“Edward Luton,” said Mr French to himself. “Hm.”

“A gentleman has called to see you, my Lord,” said the Sare Park butler, proffering a salver.

“Already?” choked Lukey. “That was quick!”

Ignoring Lady Hartwell, his Lordship took up the card which lay on the salver. It said “G. French”, the which was scarcely enlightening.

“The gentleman has pencilled something on the reverse, my Lord,” murmured the butler.

So he had. It said “de la part de Meinhoff.” Lord Sare’s neat brows rose very slightly. “Thank you, Harewood. I will see him in the library.”

“What: not in here?” cried Lukey as the butler retreated. “Edward, darling, one must see who is so quick off the mark!”

“We have been here nearly a week, Mamma,” murmured Mercy.

“But that is quick for these rural climes, my dear,” she said with a horrible moue. “Will he have been dispatched by a wife? Will he have had the remarkable nous to come of his own accord?”

“Will he be a merchant from Weymouth come to sell me carpets or coal?” said Lord Sare at his driest. “Pray excuse me.”

“Harewood would not have said it was a gentleman if it was not,” said Lukey significantly as the door closed after him.

“No, very true. And a merchant would not have asked for Uncle Edward. Um, mayhap it is the man who has that very pretty house between us and the village?”

“Yes, or mayhap it is that very pretty boy whom we saw riding the chestnut with the white blaze t’other day,” replied her mother with terrific airiness.

Mercy subsided, with a blush and a laugh.

“One could go and affix one’s ear to the door,” noted Lukey thoughtfully.

This was no idle threat. “Mamma! No! The servants would be horrified!” she gasped.

“Well, then, his silly so-called study adjoins the boring library. One could lay one’s ear to its panelling.”

“No,” said Mercy limply.

“Darling, he will never tell us, if it be anything interesting, you know. Edward is as close as an oyster.”

“I do not see,” said Mercy valiantly, “that in the present case there can be anything to be close as an oyster about. And I forbid you to do any such thing.”

Lukey gave her gay laugh and said: “Darling! So stern! Your uncle to the life!” But desisted, for the nonce.

Mercy sat back limply, feeling, not for the first time, that it was she who was the stern mamma and Mamma who was the naughty child. She was, however, quite sure there would be nothing interesting to hear at all: the idea that there could be was just Mamma being Mamma.

But for once the common-sensical Mercy was wrong and the flighty Lucasta Hartwell was right. The conversation between the two men might have been very interesting indeed—to those who had the correct clues to guide them through it.

When Edward went quietly into the library a broad-shouldered figure was standing with its back to the door, looking up at a family portrait. An Elizabethan Luton, with a pointed beard and neat ruff, fingering a gold pomander. The long hand against a plain black suit of clothes could have been Edward John Amyes Luton’s own hand. And the face behind the pointed beard was unmistakably his own face: though in the portrait the eyes were half-veiled, whilst the present Lord Sare’s normally looked limpidly ahead.

“Mr French? Good morning,” said Lord Sare politely. “I am Lord Sare.”

The broad-shouldered figure in the blue town coat turned slowly. He looked at Lord Sare expressionlessly.

“Bonjour, M. Meinhoff. Soyez le bienvenu à Sare Park,” said his Lordship, bowing politely. His face expressed as little as did the visitor’s.

“Thank you, my Lord,” said Mr French “I wondered if you would admit to knowing me.”

“I have no reason to hide the fact, M. Meinhoff,” said Lord Sare politely. There was just this slightest of emphases on the “I”.

“No? I own, I thought you might have; though certainly Luton would appear to be Baron Sare’s family name. I suppose that proves it,” he said, nodding his head at the portrait.

Lord Sare glanced up at it. “The Baron Sare of the day. One of Walsingham’s spies. Later spy-master himself,” he explained coolly.

Mr French’s eyes twinkled. “You surprise me. I suppose I had best come right out and say, I am your tenant at Little Sare, but I did not call to foist myself upon your Lordship.”

“No; you called to make sure I was, shall we say, both truly myself and truly the rightful heir to the barony.”

“Yes, well, given that you once laid claim to be the rightful heir to the Vicomté de Malmay-Gréville, and masqueraded successfully as the Vicomte de Malmay-Gréville for six months, possibly there was some excuse for me.”

Edward John Amyes Luton’s expressive mouth twitched. “Indeed. Let me assure you that there is no Lady Sare in the case.”

At this Mr French frankly grinned. “I would never have asked, sir!”

“No. I’m very glad to see you, M. Meinhoff,” he said, holding out his hand.

Mr French gripped it hard, grinning, but said: “It is French, my Lord.”

“Of course; I beg your pardon. Sit down, Mr French, please.”

“Actually it is my own name,” said Mr French, having seated himself composedly. “Old Meinhoff is my father-in-law, you see. Wanted me to change it when I married Mignonette; and I did not see any good reason to upset him by refusing.”

“Really? So you are English by birth, then? I was sure you were Dutch,” admitted Edward calmly.

“Thanks,” said Mr French, grinning. “No, I’m English, all right and tight. Born and bred in Dorset, too; though not any part of it what your Lordship would know.”

“I see. Never tell me you are come home to retire?”

“Something very like that: yes. I’ve decided that my children should settle in England.”

“Ah. And the business?” said Lord Sare, the limpid blue-grey eyes watchful.

“I'm keeping a watching brief on that. Well, the Paris office is going well, now, and the Amsterdam office will remain the centre of our European operations, but we’ve opened a London office: may do most of our business from there. Not that the Continent hasn’t treated us well. But armies rampaging up and down for thirty years at a trot haven’t done the European economies all that much noticeable good. And here in England you are undergoing considerable industrial expansion, with your Eastern interests in particular proving most profitable, while Frenchmen have been wasting their energies fighting for large patches of Europe which are not properly theirs. I think England may offer us… security,” he ended on an oddly dry note.

Lord Sare looked back at him with equal dryness. “That would seem a fair exchange for the securities you offered us when the whole of the damned Continent was for Bonaparte: yes. Er, if I may ask, Mr French, does Wellington know you're over here?”

“Lord, no, I would not presume,” said George French simply.

“But my dear man, he would be thrilled to know you were come to England!”

“Maybe. But I’m here as George French, retired merchant, that’s all. Don’t aspire to cut a great figure in Society, y’know.”

“Look, given that Wellington and Rockingham between them got Prinny to give damned Harry Ainsley a medal for blundering about the French camp disguised as a not very believable Dutchman, and that anything he might have done pales into utter insignificance compared to your contribution to England’s war chest—”

“No. Nice thought, but Sir Harry Ainsley’s an English baronet, and I’m a lad from the back streets of Dorchester with a rich old Belgian Jew as a pa-in-law.”

“Will you not at least let me speak to Wellington?”

“No, thank you all the same, my Lord. If you are wishful to do something for me…”

“Anything at all!” he said with one of his rare genuine smiles.

Mr French blinked slightly. “Thank you; that’s very nicely said, my Lord. It isn’t anything very much. Just not to let on to anyone that you know me as anything but George French.”

“Certainly. But is that all?”

Mr French rubbed his chin slowly. “You could maybe tell me where to buy some decent horses for my lad.”

“Young Gérard? Of course! How old is he, now?”

Mr French grimaced. “Twenty-two. Time flies, don't it?”

Lord Sare nodded, smiling, scratched out some names for him, and mentioned a local man who was looking to better himself in a gentleman’s stables, vouched for by Sare Park’s own head groom. And the talk turned to other places and other times they had known together…

“Oh, had an odd experience while we were up in London,” noted Mr French. “Annette wanted to do some shopping, and so Gérard and I sent her off with a Mrs Gold, whose husband is in the London office, and wandered about the City. We ended up around midday, cannot say exactly how, in a public house within a stone’s throw of the Law Courts.”

“Yes?” he said politely.

“Er—well, it was damned odd. Do you remember an Englishman who ran a gambling house in The Hague? Martin, his surname was.”

“Why, yes, I remember him perfectly,” he said tranquilly.

“Aye, thought you might. Heard he died a few months back, don't know if it be rumour or fact. He had two children, the both of them set to work in the house. Dressed the girl as a boy.” He shrugged. “Dare say he felt it safer. She was a pretty little thing, with a pointed face, and big eyes of a very unusual shade of brown, almost a yellow. You see it sometimes in Germans; don’t know that I’ve ever seen it in an English person.”

“I never knowingly met the children. Though I have been to the house.”

“I am sure,” said Mr French on a dry note. “Well, thought I saw the girl at this public house. She was with a crowd of very odd-looking people: think they might have been actors from Drury Lane.”

“Oh! Yes, it is quite nearby!” he said, smiling.

Mr French could not quite see why he was smiling: he gave him a sharp look but did not remark on the point. “Yes, well, I was as near to her as I am to your Lordship now—no, nearer, in the crush—and I could not but notice the eyes. I’m sure it was the Martin girl.”

“An odd coincidence. Though Martin was English, so perhaps she has relatives here?”

“Aye, more than like. My God, that was a place,” he said with a reminiscent smile. “Every method of marking cards known since the dawn of time.”

“Pretty much, yes!” agreed Lord Sare with a laugh. “Anyone but Martin would have turned the place into a gold mine, but he let it run to wrack and ruin.”

The man whose ability had led to his being taken out of the counting-house by old Pierre Meinhoff and groomed to fill the old man’s very shoes shrugged. “No business sense.”

“Quite.”

They talked of other places and faces, and finally shook hands very heartily.

After the door had closed behind the visitor Lord Sare went slowly over to the portrait of Walsingham’s contemporary and stared at it hard for some time. Eventually he said to it: “You are perfectly right, Henry Luton, and I shall be damned careful. Though I think it is all pure coincidence. On the other hand, Meinhoff—or French, as I suppose I should call him—has one of the cleverest heads in Europe. And if he can sound perfectly Dutch not merely to me but to Kees van Kleef, I dare say he can introduce that so-convincing slight Dorset burr at will into his English, too. Well, it can do no harm to check that part of his story. Ye-es… But the name of Bully Matt Martin,” he concluded grimly, “is cropping up rather too frequently for comfort, is it not?”

Henry Luton’s eyes remained half-veiled. He was clearly watching something just out of range of the viewer. Sensible man.

George French went back to Little Sare and ate a hearty meal. He would not truly have been surprised to see Edward Luton masquerading as anything at all: he had known him not only as the Vicomte de Malmay-Gréville, but also as a Mr Hall, an American gentleman with strong republican sympathies, as a Signor Giotto, and as a Capitaine Le Greux. But as, on the last occasion he had been in his company, there had also been present one, Arthur Wellesley, and one, Herr Blücher, not to mention the Prince of Orange, plus various chastened-looking gentlemen who had unwisely invested in the Emperor’s cause rather than the Allies’, and as Wellington had referred to him as “Colonel Luton” and addressed him as “Edward”, and as he had been wearing the uniform of a very distinguished English regiment indeed—with major’s insignia, so clearly it was a field promotion—Mr French saw very little reason to doubt that it was his real name.

“There was something, though, wasn’t there?” he said to himself, strolling out into the ruins of Little Sare’s garden. “Aye… Too careful? Well, he always was a prudent man, reason he’s lived this long. But… Aye, too careful.” The warm Dorset burr was strong in his voice. He looked around the waste that had been the so-called shrubbery, and smiled. “Aye. Roses, I think. Always did want a rose garden, like a real gent,” he murmured.

Next chapter:

https://theoldchiphat.blogspot.com/2023/02/stage-fright.html

No comments:

Post a Comment